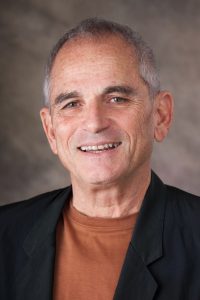

Editor’s note: Stanley Lombardo’s presentation of Homer’s Iliad at 3:30 p.m. Thursday in the Hall of Philosophy has been canceled. The book still serves as an official Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle selection.

Stanley Lombardo’s translation of Homer’s Iliad begins with a declarative word — short, but in all caps: rage.

That’s what drew President Tom Becker and Sherra Babcock, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, to the work.

“It’s the original war story,” Babcock said. “And it begins with the word ‘rage.’ The question of the week is, ‘Are we built with some rage, something that suggests war is almost hardwired?’ That’s a question we’re going to be asking all week.”

Lombardo’s translation is this week’s Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle selection.

Lombardo has translated works from across the world, including the Tao Te Ching, Sappho’s poems, and Dante Alighieri’s Inferno. He previously visited with the CLSC in 2007 to present his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid.

For Lombardo, the translation process involves falling in love.

“When I fall in love with the poets’ voices — it’s hard for me to describe how this works,” Lombardo said. “I can’t translate anything — I can do hack work, and it might be OK — but I can’t really translate anything unless I hear the voice of the original poet somehow as my own voice, or hear my voice as the voice of Homer or Virgil or Ovid or Dante. It’s a meeting of minds, you might say.”

And after he falls in love, Lombardo said, there’s a bit of a gestation period, which can range from a single year to decades.

He recently finished his translation of Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, a project he said was 30 years in the making. Iliad, which he first read in Greek as an undergraduate, took six years.

Lombardo’s work is the selection for Week Eight, the theme of which is “War and Its Warriors: Contemporary Voices.” Homer’s work is thousands of years old, so it’s anything but contemporary.

But Babcock said Lombardo’s translations, as well as his verbal delivery of them, brings a freshness to one of the world’s oldest war stories.

“Listening to him read the classics makes you want to go back and read the classics,” Babcock said. “His translations are also a little bit looser, more poetic and more emotional.”

Lombardo provided his own example of that contemporary effect.

He was once doing a reading from his translation of the Iliad, reciting a scene between Achilles and Hector, when he was joined by some unexpected visitors.

“These people on the street came in, kind of half-stoned,” Lombardo said. “They came through the crowd and sat right in front of me on the floor, just gawking up at me. And as soon as I finished, one of them stood up, turned around to the audience, hitched up his pants, and said, ‘Well, Hector — that was a good man. But Achilles — now there’s a real son of a bitch.’ ”

Achilles may be a compelling and complex S.O.B., but Lombardo said he’d like to focus his on the women of the Iliad.

He said war is a crucible that shows what humans are truly made of, and Homer’s women are wonderfully diverse examples of that theme.

The Iliad features mothers, queens, wives, priestesses, lovers, goddesses and the most beautiful woman in the world. But what’s essential is their humanity, Lombardo said, even when a character is divine, such as Achilles’ mother Thetis.

“Even though she is a goddess, she shows us what a mother is going through when her child is off at war,” Lombardo said.

He said his favorite character to bring to life was Helen.

“Each of Helen’s speeches in the Iliad reveal a different aspect of her personality, and I would look forward: ‘Where’s the next Helen speech?’ ” Lombardo said.

It’s easy to reduce Helen down to her most famous trait: her beauty. But Lombardo said Homer gives the reader enough to show that those iconic characters are actually much more complex than they may seem.

“Homer manages this in just a few deft strokes,” Lombardo said. “That’s the genius of Homer: economy. He always gives you what’s absolutely essential and you feel there’s a human being in front of you.”

Helen doesn’t appear often in the Iliad, Lombardo said, with only a total of four speeches.

“But there’s something really entrancing about this character,” Lombardo said. “People are fighting this enormous war for her, and she, herself, is half-divine. At this point, when she appears in the Iliad, she’s consumed with guilt and despises herself. But does she really? Is it just her self-presentation? There’s a lot of tension in this character.”

The deeds of Helen, Achilles and Hector may seem far off for a contemporary audience, but Lombardo said the power players of the ancient world and the people of today have something in common.

“It’s our mortality and how we touch each other’s lives,” Lombardo said.

Lombardo said people might not think that happens much in the Iliad, but the interactions in the scenes he plans to read show the opposite is true.

“Whatever our essential nature is, it functions through human relationships,” Lombardo said. “And this is ultimately what’s of value in life. Achilles spends most of the Iliad just brooding inwardly, and it’s when he comes out of that that he expresses, realizes, brings forth his true nature.”

And once Achilles can let go of his rage and see what he’s wrought, Lombardo said, his humanity becomes clear.

“The very first word of the Iliad is ‘rage’ — the rage of Achilles,” Lombardo said. “He doesn’t let go of this. It assumes different forms, and he doesn’t let go until Hector’s old father is there kneeling before him and Achilles looks at him. And he becomes human, finally, you have to say. He’s been superhuman throughout the entire epic, and his basic humanity comes out in that situation.”

Moments such as those show a long view of the world’s common culture, Lombardo said, and proof of why the world still needs the classics.

It’s something Lombardo has learned as he’s translated widely.

“If you can have a vision of humanity as persisting and evolving as one continuous organism through the centuries, that’s the best perspective that you can have,” Lombardo said.