For those struggling to understand transhumanism, it may be best to start at the finish. By and large, transhumanists’ ultimate goal is to reach what’s called singularity: a point at which man achieves immortality by merging fully with machine.

Experts pin that date between the 2030s and never. In between now and then, transhumanists seek to implement vast social, political, biological and even moral revolutions as people use technology to enhance themselves and usher in a new age of human evolution.

Now if that all sounds just a bit to “Space Odyssey” to you, you’re not alone. In 2002, the Vatican condemned the tenets of transhumanism as “radically immoral,” among other criticisms the movement has received about the feasibility and ethics of technologies such as artificial intelligence. Much of the religious problem is fairly intuitive: If, as the Abrahamic faiths teach, man was created in God’s image and therefore just below God, and transhumanists use technology to become superhuman and achieve immortality, then where is the room for God?

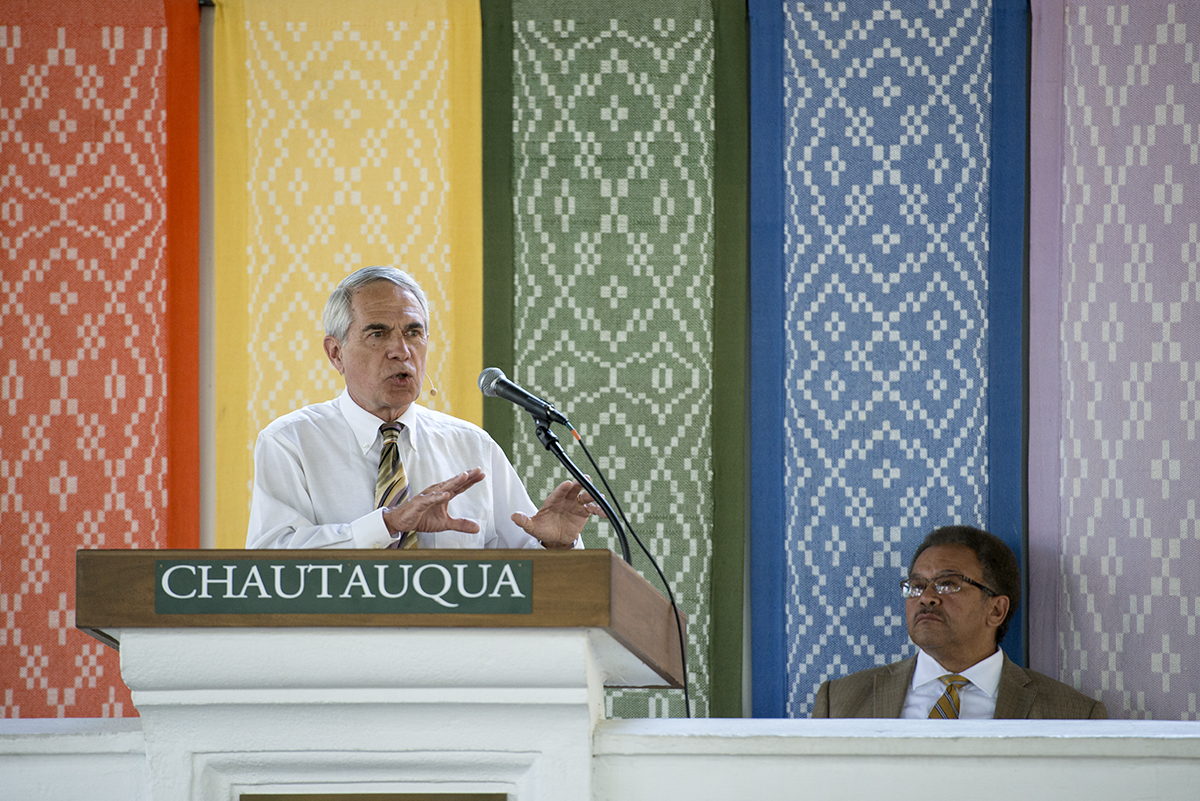

The Rev. Ron Cole-Turner, a longtime Chautauquan and founding member of the International Society for Science and Religion, took to the Interfaith Lecture platform Monday at the Hall of Philosophy to assuage any ethical concerns people may have about what he views as the next epoch of humanity. His argument was equally intuitive: people have always tried to enhance their lives. Technologically advanced transhumanism is the next step.

Cole-Turner cited Chautauqua Institution itself as his first example. With its four pillars of religion, education, arts and recreation, Chautauqua has been focusing on human advancement for more than a century, Cole-Turner said. Transhumanism just adds a fifth pillar: technology.

“If you don’t like transhumanism, what are you doing at Chautauqua?” Cole-Turner said. “This whole place is about human enhancement.”

But it’s not just Chautauqua. From drugs such as Adderall that allow students to concentrate for hours to cosmetic surgeries and computer chip/human brain interfaces that allow for controllable prosthetics, people have been using technology to improve themselves in every dimension of life, Cole-Turner said. Just take the Olympics, Cole-Turner said, where the drive for physical enhancement has led Russia to fund a nationwide doping program.

There’s even technology for moral enhancement. Cole-Turner said some pastors have been tempted to do away with marriage counseling all together and send couples home with nasal sprays of oxytocin, a chemical that acts as an antidepressant and promotes trust. It’s sometimes called the “cuddle hormone.” He compared it to the fairies’ magical potion in Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream that makes people fall in love with the first person they see.

Cole-Turner said some may be concerned that with such technological fixes, people will no longer need to work for things, but he argued that was not the case.

“You don’t take a pill to become an outstanding athlete,” Cole-Turner said. “You may take a pill to make you a better, more outstanding athlete, but you still better go to the gym. Same with education. No pill puts information, much less wisdom, into your brain.”

Modern transhumanism grew from a handful of scientists and science fiction writers. It was first discussed widely in the netherworld of internet chatrooms, only recently gaining widespread scientific legitimacy to the point that Elon Musk is pouring millions into developing artificial intelligence. and Google has hired one of the leading transhumanist thinkers, Ray Kurzweil, as a full-time employee. But Cole-Turner instead dated the movement back to Dante in the 13th century, who wrote, “Trasumanar significar per verba/non si poria” or “to go beyond the human, to say what that means, is not possible.”

“He writes the rest of poem to try to do it, but he’s in a well-founded tradition in asking, ‘What is it that lies beyond humanity?’ Something beyond words,” Cole-Turner said.

Cole-Turner then went back further, to the Scriptures. Psalm 82:6 tells the people “you are gods” and in the Christian vision of the Second Coming, Cole-Turner said, humans will become like Christ. Cole-Turner then returned to Italy, this time Renaissance Florence, for what he sees as the defining application of those Christian and deeply human teachings. In what’s become known as the manifesto of the Renaissance, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola writes that God has defined every creature, except for humans who have no essential nature and must define themselves.

“I look at that not as Christian humanism, but as Christian transhumanism,” Cole-Turner said.

Still, Cole-Turner urged some caution in applying transhumanist technology. For example, he said CRISPR, a new gene-editing technology scientists say may soon be used to cure diseases such as HIV and prevent cancer, could also be used to “hack” other people’s genomes for nefarious purposes.

For that reason, Cole-Turner said, humanity has to define its direction and then develop technology to go there, rather than blindly following technology. He laid out three principles he thinks should guide all transhumanist innovation.

First, have caution but do not fear new innovations because whatever guided humanity through the first 7 million years of human evolution will guide us into the future. Second, don’t leave science to scientists; make sure religion and humanities mold the direction of technological development. And finally, don’t use transhumanism to expand your own ego and sense of self, as many seek to do.

“If I use these technologies at all, [I must use them] not to expand myself but to give, to serve, to love, to care for, and above all not seek my own elevation but that of others, knowing that when I truly do that — and this is the Christian paradox — that is when I am most fully alive,” Cole-Turner said.

(Photo by Sarah Holm.)