Everyone knows that rock ‘n’ roll emerged in the mid-1950s as a primal cri de coeur from disaffected teenagers fed up with the soul-killing compliance imposed upon them by their hopelessly square and clueless parents.

Everybody knows that rock ‘n’ roll is all about rebellion.

Right?

Wrong, according to Richard Aquila, a historian, teacher and writer who has spent the better part of a lifetime listening to, chronicling and commenting on rock ‘n’ roll. The author of That Old Time Rock & Roll: A Chronicle of an Era, 1954-1963, Aquila contends that early rock ‘n’ roll was a lot tamer than people today think. Aquila will offer up his somewhat revisionist history, along with illustrative cuts of music, in a program called “Sh-Boom! Or, How Early Rock & Roll Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love America’s Cold War Culture” at 3:30 p.m. today in the Hall of Philosophy as part of the Oliver Archives Heritage Lecture Series.

Aquila is the writer, producer and host of the syndicated show “Rock and Roll America” on NPR and his latest book, Let’s Rock!, will be published this fall.

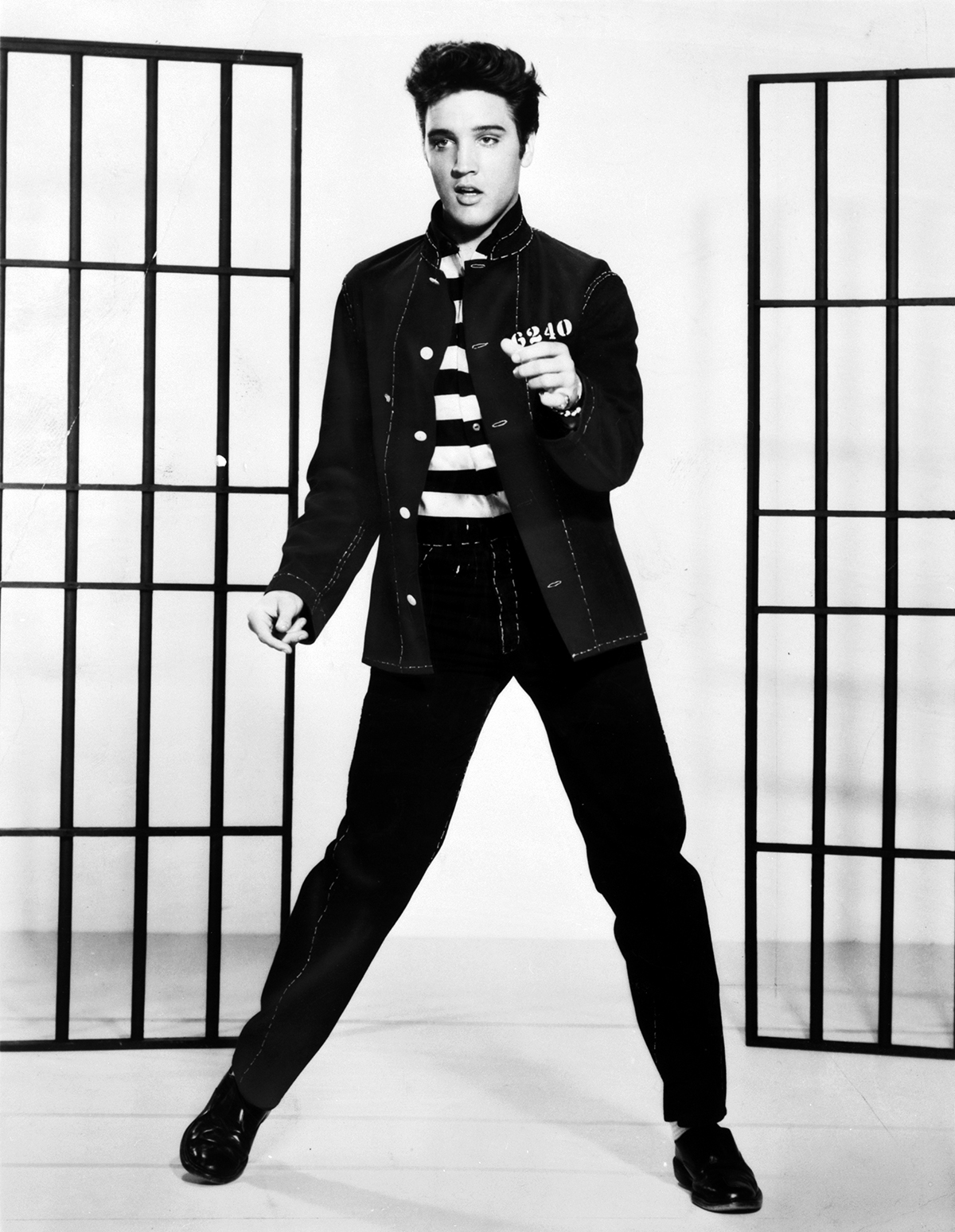

“When people think of early rock, they think about the rebellious aspects of it, like Elvis swiveling his hips, Little Richard screaming or Jerry Lee Lewis pounding the keys of his piano,” Aquila said. “But really it reflects the conformity and consensus of the 1950s in America and the politics of the Cold War.”

Elvis Presley may have cut a shocking figure with his pompadour hair and sideburns singing Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” but he also represented something reassuringly wholesome. Ed Sullivan called him “a nice, clean boy.” Elvis enlisted in the Army when he probably could have avoided it. He was proudly religious. He loved his mother.

“Elvis seemed revolutionary and rebellious to some Americans, but other people saw his as very traditional,” Aquila said. “I mean, he sang ‘Peace in the Valley.’ ”

Aquila compares Elvis to another performer whom many considered his antithesis, the white bucks-wearing heartthrob Pat Boone.

“Elvis sold more records and was higher on the rock ‘n’ roll charts than anybody else, but Pat Boone was No. 2,” he said. “Radio stations had popularity contests all the time and he won as many as Elvis.”

Aquila sees the two singers as, if far from equally talented, at least equally influential.

“Nine out of Pat Boone’s first 10 hits were covers of black rhythm and blues artists,” he said. “Maybe the worst thing I have ever heard is Pat Boone doing ‘Tutti Frutti.’ Little Richard screams ‘wop bop a loo bop a lop bom bom!’ Pat Boone croons it. It’s horrible. But he was expanding the market for rock ‘n’ roll and R&B. They were vanilla versions, yes, but they exposed white kids to a broader range of music.”

The dichotomy of Presley and Boone was not unique, Aquila said, pointing to Little Richard and Liberace.

“There were tensions between the rebellious and flamboyant and the middle-of-road,” he said. “There was no one like Little Richard. He was gay, black, sexually suggestive. He was so outrageous and over the top, it was hard to take him seriously. Liberace was similar in a less-threatening way.”

Chuck Berry, Aquila said, incorporated a combination of hip and square that was wildly popular.

“He consciously sat down to write for that audience of white kids,” Aquila said. “He was pretty far removed from being a teenager himself, but he picked up on the youth culture, the cars and school stuff.”

He cited Berry’s “Back in the U.S.A.” as a perfect reflection of American values at the time.

“Here it is the midst of the Cold War,” Aquila said. “He’s flying back from Europe or wherever, and he’s extremely happy to back in America with all of its consumer goods. Everything you want, you can get it in the U.S.A.”

The assassination of John F. Kennedy ended rock’s early era, Aquila argues.

“The music changed when the country changed,” he said. “There was a lot of violence. You had the civil rights movement and Vietnam. People weren’t as innocent. The Beatles and [Bob] Dylan changed things dramatically, too. The music wasn’t just reflecting the culture. It was shaping the culture. In the early days, you had Top 40 radio and people were listening to the same songs; it was very homogenous. FM radio killed that. Ninety percent of the artists who were popular before 1964 were blown out of the water. They’re largely forgotten. They don’t fit into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s party line about rebellion.”

So, should Boone be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

Aquila laughed.

“Look, I never liked Pat Boone’s music,” he said. “But, yes. He influenced rock ‘n’ roll a tremendous amount. He should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.”