The National Geographic Emerging Explorer Program recognizes trailblazers from every walk of life: “scientists, conservationists, storytellers and innovators” are all eligible for the acknowledgement, not to mention research funding, that acceptance confers.

But though Explorers can come from any number of different fields of study, they are all alike in — as the program website puts it — “making a difference and changing the world.”

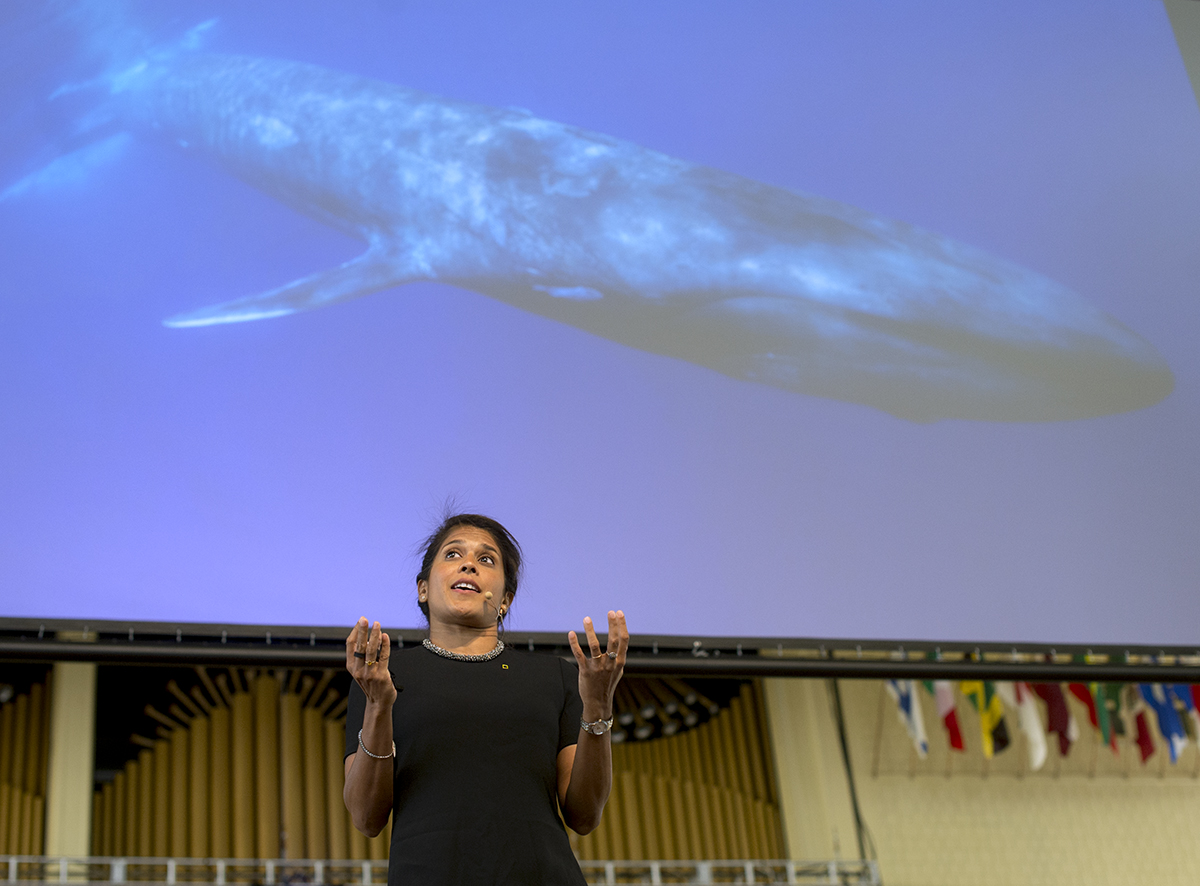

Delivering back-to-back lectures Wednesday morning in the Amphitheater as part of Week Two, “The Human Journey: Origins, Exploration and Preservation,” marine biologist Asha de Vos and lion biologist Thandiwe Mweetwa are recent inductees of the 2016 class of Emerging Explorers.

Despite researching very different topics, they both emphasized the same underlying thesis: from the seas of Sri Lanka to the valleys of Zambia, environmental conservation is a pressing issue worldwide.

Working to save the largest animal on the planet

At 5 years old, Asha de Vos painted a picture of a blue whale.

Though perhaps not 100 percent accurate anatomy-wise, her childhood artwork now seems an apt predictor of what her life has come to look like years later.

“The passion hasn’t stopped,” de Vos said. “And it’s nice to think that that dream that I had as a 5-year-old has carried me on to today.”

De Vos traveled 30 hours to get to Chautauqua Institution from Sri Lanka, but she’s no stranger to travel; she had her “eureka moment” in 2003 while working in Sri Lanka and the Maldives on a research vessel that was in the process of circumnavigating the earth.

The team was tracking sperm whales using underwater microphones (called “hydrophones”) in order to measure marine toxicity and collect any other data they could get. But one day, that all changed.

“I was the observer … so I was standing up there, looking out for these sperm whales,” de Vos said. But when she finally found something, it “was not a sperm whale. … I (thought it was) a blue whale.”

Her hypothesis ended up being wrong, but not because the sighting was, indeed, just a sperm whale.

“I start to think I’m losing my mind,” de Vos said. “Because instead of one blue whale, I was seeing six blue whales.”

Despite being “the largest animals that have ever grown on the planet,” all of the whales were in an area the size of a soccer field. Thinking back to the undergraduate education she had just finished, de Vos recalled that “blue whales undertake long-range migrations between cold feeding areas and warm breeding … areas.” And the waters south of Sri Lanka were decidedly tropical.

“I was so excited because I was thinking that my eureka moment was going to be me, the first person on the planet to ever watch blue whales mating,” de Vos said.

But the ship approached and they saw that there was “no hanky-panky going on … no babies being born.” Not wanting to have wasted time for no reason, de Vos asked the captain to let them wait there another half-hour.

“And I’m sure glad I did, because this is what I saw next,” de Vos said, indicating a picture of bright red globules. “This, ladies and gentleman, is a pile of whale poop.”

But weren’t blue whales only supposed to feed (and, subsequently, poop) in cold waters, like de Vos had learned in undergrad?

The implication was clear: “a population of the largest animal that had ever roamed the planet had figured out how to feed in a part of the world that we were not expecting them to be.”

As she continued researching the whales in the following years, they turned out to have developed a whole host of specialized behavioral adaptations. They had a special linguistic dialect and unique diving behavior, and were the only known nonmigratory blue whales in the world. They were also technically “pygmies,” since they grew to 80 rather than 100 feet.

But their unique location also carried with it unique risks.

The waters around Sri Lanka are a hotspot for shipping routes, and shipping “around the Indian Ocean has actually quadrupled” since the ’70s. When the massive boats meet the massive whales, the results can be deadly.

Showing a picture of a dead blue whale “wrapped on the bow of a container ship” and describing another one “with a massive propeller gash,” de Vos said that for every one such whale that gets discovered, an estimated 10 more do not.

This is especially egregious because 90 percent of the ships in the area don’t even stop at Sri Lanka.

“At the end of the day, ship strike is all of our faults … we are all to blame,” de Vos said. “But the key thing is, we don’t only have to be part of the problem; we can also be part of the solution.”

When the hunters become the hunted

Thandiwe Mweetwa comes from the Luangwa Valley in Eastern Zambia, “one of the most amazing places … and one of the last remaining huge wildlife areas on the (African) continent.” In addition to being nicknamed the “Valley of the Leopard,” the region is also filled with wild dogs and the country’s largest lion population.

But as with that of Sri Lanka’s waters, the Luangwa Valley’s biodiversity today carries with it certain ecological pressures.

“Despite all the wonderful things this area has to offer, we also have our fair share of problems,” Mweetwa said. “Population in the area has increased in the last decade and a half, and there’s a lot more pressure from human activity.”

With people and animals competing for limited food and space, the predators for which the region is known have been put at risk. It is in the pursuit of protecting them that Mweetwa has worked with the Zambian Carnivore Programme as a senior ecologist.

Using radio collars to track the locations, numbers and habits of lions and wild dogs, as well as taking advantage of “opportunistic sightings,” the Programme collects data to help better protect the animals from poaching and other threats.

“Our aim is to limit human-induced mortalities,” Mweetwa said.

But although she does do some in-the-field medicine to help heal injured predators, Mweetwa emphasized the importance of education and outreach in creating lasting change.

“Our outreach project is focused at local secondary school students,” Mweetwa said. “We want to promote interest in conservation … so we provide a support system for motivated students (who) are interested.”

A typical work day for Mweetwa consists of going out into the field and tracking “different social groups” of the animals; for instance, a pride of about 80 lions. As the team tracks where the predators go, what they eat and how they hunt, they hope to learn how to better protect them.

“A lot of the time we are going to these very difficult, hard-to-reach places,” Mweetwa said. But up-close sightings of wildlife, like when she encountered a trio of female lionesses protecting a young cub, “(make) it all worth it.”

But the work of conservation is not easy, especially because the nature of the threats is always changing. A lot of this has to do with human activity.

For example, it used to be “almost impossible to keep livestock in the valley” because of the rampant tsetse fly populations. “But over the years, human-induced change to the habitat” has reduced the tsetse presence, Mweetwa said, allowing people to bring livestock into the valley and thus prompting conflict between those people and lions trying to kill their animals.

“What this problem speaks to is the need for continued scientific research and exploration (into) these problems,” Mweetwa said.

But research in and of itself is not enough; Mweetwa presented a quote from National Geographic Explorer Prasenjeet Yadav: “Communicating science is as important as practicing it.” To government officials and laypeople alike, outreach about environmental issues goes hand-in-hand with research on them.

Going forward, Mweetwa suggested three answers to the question, “What can we do to make conservation a success in the 21st century?”

Her solutions include investing in people living alongside wildlife, connecting people back to nature and making the conservation movement “a bit more inclusive (and) a bit more compassionate,” even toward those who cause the problems it works to solve.

“We do not have the luxury of alienating people,” Mweetwa said to applause.

Ultimately, protecting these species is a “collective global responsibility” that, though a daunting problem to face, can be changed for the better through science, research, education and outreach.

“Nature … is very resilient,” Mweetwa said. “And it can come back quickly if given a chance.”