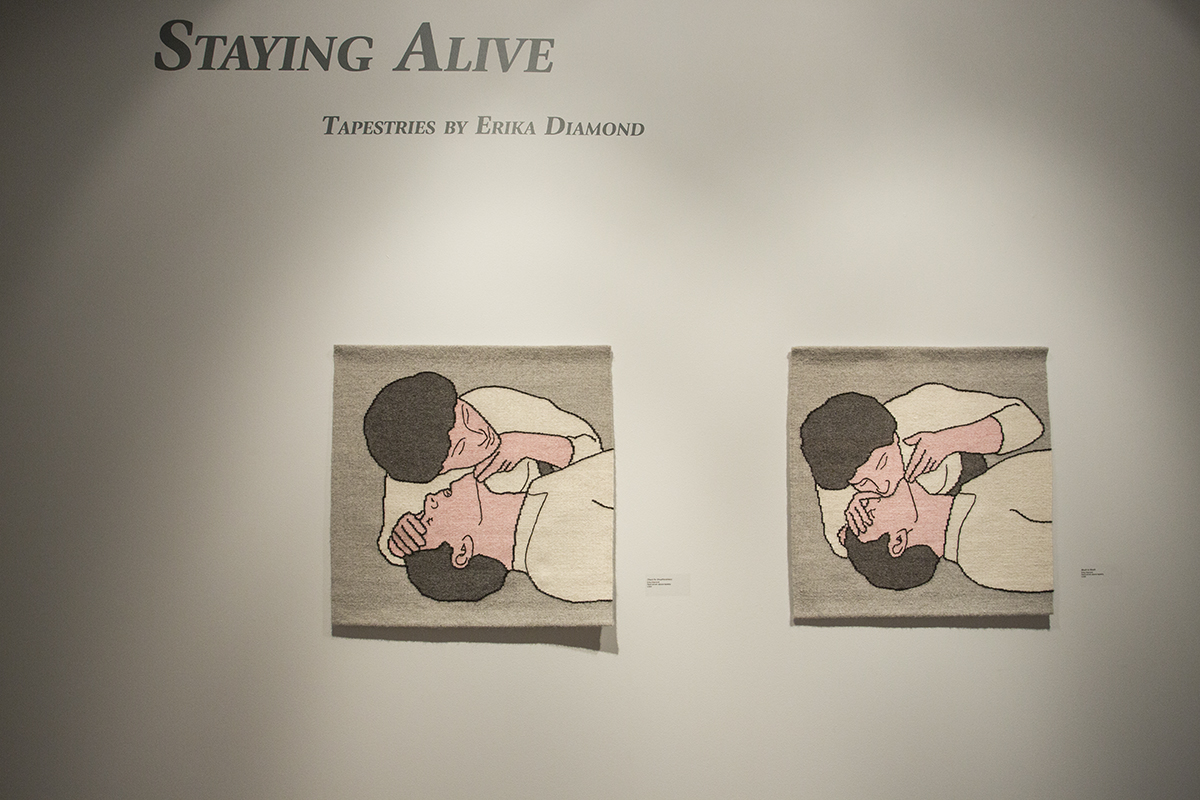

The images in First Aid manuals and airline emergency instruction cards don’t immediately bring to mind the art of tapestry, but that is where Erika Diamond’s imagination wandered when she thought about these familiar illustrations. Diamond holds an MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University in textiles, having earned her BFA in sculpture at Rhode Island School of Design. Her solo exhibition, “Staying Alive: Tapestries by Erika Diamond” is currently on display at the Strohl Art Center’s Bellowe Family Gallery.

The history of the decorative tapestry dates back to ancient Greece, but grew in popularity in the 14th and 15th centuries, at which time the German, French and Dutch textile industry prospered by selling wool tapestries to decorate palaces and castles. Many had gold woven into them, and were later burned to recover the gold thread. The popularity of the tapestry was in part due to its portability, as they could be rolled up and transported from one castle to another. But they also served a practical purpose: they were used as insulation on cold, stone castle walls.

The most common motifs in Western tapestries are religious, mythological or of the hunt. So, how did Diamond conceive of correlating common, 21st-century emergency iconography with the labor-intensive craft of tapestry? Historic tapestries depicted human interaction, the struggle for survival, danger, and hope. Scenes were of war, the apocalypse or other narratives, often of life eluding death. This theme, ironically, also appears in the straightforward, diagrammatic pictures in first-aid manuals and airline seat cards that were the inspiration for Diamond’s tapestries. The hypothetical struggle to save a life because you have been thrust into an urgent situation is a theme in war and in instructional illustrations of what to do in a 21-century emergency.

Diamond wove all of the tapestries on exhibit by hand on a loom, the largest about 36” long. Most depart from the monochromatic safety illustrations we are familiar with, as bright blues, greens, yellows and golden thread appear in many of her works. In “The Three Fates,” a group of crash survivors calmly hold onto their airline flotation devices. Representing the Fates, who in mythology control the span of human life, they now bob listlessly in the ocean, awaiting their own rescue. Like a Madonna and Child, another tapestry depicts the mother calmly and lovingly placing the decompression mask on her child’s face, as if no one is phased by the danger of the plane going down. In “Check for Breathlessness,” one figure, unflustered by his unconscious victim, leans down to see if he can hear breathing.

The participants’ expressions are so familiar, like on the well-known tapestry “The fourth horseman: Death” from the 4th-century Apocalypse Tapestry. In that image, an emotionless observer watches as a rotting corpse on a horse trots by. This unusual, yet customary choice to leave out the actual emotion of the participants in disturbing images, perhaps, speaks to our collective human inability to handle the potential horrors of our existence. Thus, the analogous choice, in both Medieval tapestries and contemporary pamphlet illustrations to exclude our reactions as our plane is about to crash, as we are confronted with the need to save a life, or as we see death wandering by on a horse, speaks to our human limitations. Removing sentiment and replacing it with logic is much more palatable. How to act rationally in the face of danger is seen in the common airline safety card images and in tapestries of bystanders watching horrific scenes unfold. In Diamond’s work, tapestry is not only the medium for her to recreate these images, but it also conveys her underlying conceptual message.

“Staying Alive: Tapestries by Erika Diamond” continues through July 23 at Strohl Art Center.

Melissa Kuntz has written for many publications, including Art in America magazine and the Pittsburgh City Paper. Her paintings and drawings have been shown in Canada and the U.S. She is full professor of painting and drawing at Clarion University of Pennsylvania and is working part-time toward a Ph.D. in applied sociology at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.