Brian Skerry started diving before he started taking photos, but only barely. Compelled to share his experiences below the ocean’s surface with others, it was only a matter of time before underwater photography became as much a part of his repertoire as scuba.

Now a marine wildlife photojournalist and a National Geographic Photography Fellow, Skerry led his Tuesday morning audience through some of his favorite stories he’s done with the magazine. But though the presentation in the Amphitheater featured an array of stunning photos from his trips, he doesn’t see his job as just about taking pretty pictures.

“In the beginning, I just wanted to make interesting photographs; beautiful pictures of animals and places that interested me,” Skerry said. “But there’s been somewhat of an evolution in my career, in that over time, I began to see a lot of problems … so as a journalist, I felt a sense of responsibility and a sense of urgency to begin turning my cameras toward these issues.”

But before Skerry could tackle literally planet-sized issues like climate change and overfishing, he had to start somewhere. It was as a young boy growing up in Massachusetts, reading National Geographic and watching Jacques Cousteau documentaries, that the groundwork was laid for the lifetime of work and activism to follow.

Even now, though, that childhood sense of wonder remains.

“The ocean is really the perfect place to work as a photographer because it really is filled with mystery,” Skerry said. “So much of it remains unexplored and on any given day, you just never know what you’re going to find.”

Given that 98 percent of the planet’s biosphere is in the ocean, “it really is in our best interest to explore … (and) conserve it.” Skerry hopes that his marine photography, and its capacity to blur the lines between science and poetry, can play a part in accomplishing both those ends.

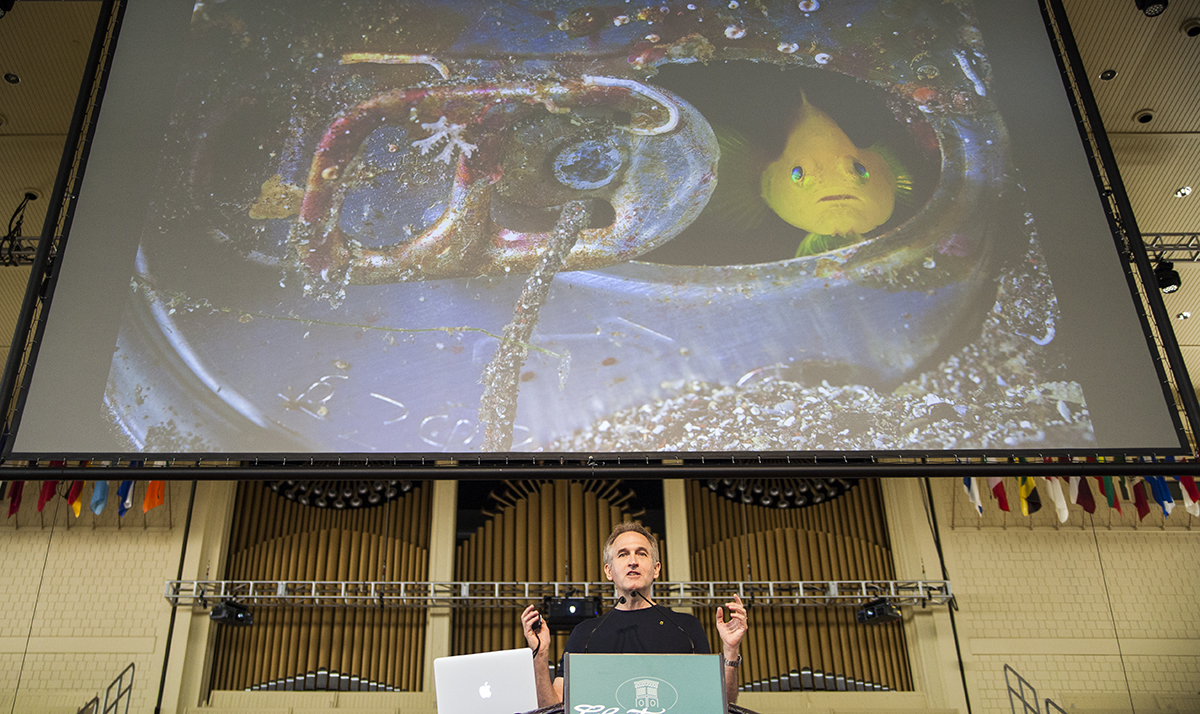

Skerry showed a picture he took of a tiny yellow goby fish poking its head out of the mouth of a soda can and said his work is all about finding those “precious frames” that can engage readers and tell them stories. For instance, ones about the impact of human waste on marine ecosystems.

Skerry started combining photojournalism with political engagement during one of his first major National Geographic projects, focused on the harp seals of Nova Scotia. Migrating south to mate and give birth, the seals need ice sheets on which to rest while the pups are weaned. But climate change is drowning many of the babies.

“The ice has become thinner and thinner, and some years there’s been no ice at all,” Skerry said. “And on those years, the pup mortality rate has increased to 100 percent.”

Soon after that story, Skerry covered “the global fisherman crisis.” Standing in front of a picture of a massive swordfish caught in a net, Skerry explained how he’d been inspired by a scientific paper stating that 90 percent of the ocean’s big fish have vanished since World War II.

“I wanted to treat it more like war photography,” Skerry said.

With species like the bluefin tuna now so rare that a single fish can sell for over a million dollars, thanks in part to the indiscriminate killing of industrial technologies like the bottom trawler, Skerry presented photos of dead sea life as he explained how modern eating habits and fishing practices threaten “collapse and extinction.”

One picture of a dead thresher shark splayed out in a net seemed particularly powerful.

“It sort of struck me as a crucifixion,” Skerry said. “And I thought that maybe an image like this would give some empathy to (the) statistic” that more than 100 million sharks are killed every year.

The question of how to best encourage shark protection was a difficult one for Skerry, since many see the animals as monsters. Ultimately, he worked with National Geographic to do back-to-back stories on three different shark species, hoping to present each as unique and worth saving.

The first piece highlighted tiger sharks. Though they are viewed as killers, Skerry’s photography shed light on their other characteristics. A picture of one swimming through algae was meant to evoke a terrestrial tiger “sneaking through the grass,” while one of a shark wounded by fishing hooks revealed the human impact on the creatures.

The next story pivoted to shortfin mako sharks, about which Skerry said there is “something very special about being in (their) presence.” Although their ambush-style hunting can make them “pretty scary,” Skerry said that actually finding the elusive creatures is a struggle in and of itself.

“I learned that there were some shark dive operators around the world who were starting to play music on underwater speakers as a way of attracting certain species of sharks,” Skerry said.

However, “there was only one type of music that seemed to work for makos.”

AC/DC’s “Thunderstruck” began to play over the Amphitheater soundsystem.

“These are badass sharks,” Skerry said.

The third part of the series covered the oceanic whitetip shark, which was “the most abundant large animal on planet Earth” a few decades ago and is today in “99 percent decline.” This story presented a good opportunity for Skerry to cover a species on the verge of extinction.

In addition to that trio of shark stories, Skerry did a recent one on great whites. Despite their enormous size, the great white shark “remains largely enigmatic,” and Skerry hoped his coverage could shed some light on the species. Shark cages allowed him to reveal “more of the animal’s world” by getting up close to the pickup truck-sized predators.

The great white coverage became especially relevant off the coast of Massachusetts, where their numbers have blossomed in the last few years thanks to changes in local seal populations. Yet despite their large presence, capturing them on camera proved difficult. This forced Skerry to test new techniques.

“With some funding from National Geographic, I built this very elaborate seal decoy … it had fiber-optic cables and video cameras inside,” Skerry said.

Although the first model didn’t work, a later one did, allowing Skerry to capture some up-close pictures of a great white bursting out of the water to eat the pseudo-seal. The shark attacked so close to the shoreline that beachgoers were visible in the background of the shot.

The last story he discussed was a follow-up to his earlier fishing crisis work, this time focused on the need for legal protection of marine ecosystems. Explaining how New Zealand’s establishment of a coastal marine protected area caused a snowball effect that ultimately replenished local fish populations and regrew kelp forests, Skerry recalled an interaction with a longtime diver who’d been amazed by the transition.

“He told me that he believed that the marine life was better here today than it was when he started diving in the 1950s,” Skerry said. “And as I left him … it sort of dawned on me that nobody’s ever said that to me. … So that’s the message: The ocean can heal itself.”

Of course, it can only heal itself if humanity allows it to do so. Playing video clips of Presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan calling for environmental protection, Skerry noted that the creation of these protected zones should be a bipartisan policy objective.

Even the places where Skerry has shot that seem untouched by humans “could so easily” be wiped out by trawling nets or other human activities.

Following President Barack Obama’s recent expansion of protected Hawaiian waters under the Antiquities Act of 1906, Skerry had the opportunity to go snorkeling with him. Showing the audience pictures of the former president looking at the sea life, Skerry said “these are the very first pictures ever made of a U.S. president underwater.”

As he began to close out the lecture, Skerry quoted former President John F. Kennedy and said that the percentage of saltwater in the human body is the same as that in the planet’s oceans; the two are inextricably connected.

“We’re at a moment in history where we understand the problems, (and) we know what the solutions are,” Skerry said. “And will we … take those actions to protect the planet for the future, or will we just bear witness to the continued destruction?”

He did not provide an answer.