Guest Column by Cathrael Kazin

I believe passionately in the transformative power of higher education. Being able to attend New York City public universities — free — lifted my parents out of poverty and created the foundation for the remarkable professional careers they went on to have. (Today, they would be labeled ESL and first-generation, but fortunately, they didn’t know this at the time.) My own life has been shaped by the educational experiences I was privileged to have.

But the predominant model of higher education has not changed substantially since I went to school, or even since my parents went to school. As a result, it is wholly unprepared to meet the demands of the future. But in fact, it doesn’t even work for the present: as Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa said with masterful understatement in Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses: most college graduates “are failing to develop the higher-order cognitive skills that it is widely assumed college students should master.” These include the ability to distinguish the viewpoints of two opposing editorials, or to even to distinguish fact from opinion.

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that higher education prepares students poorly for employment: just 11 percent of employers believe new graduates are well-prepared for the workplace.

And that’s the students who get a college degree. In fact, just over half of all students who begin a bachelor’s graduate within six years. The statistics for students of color are even more devastating. This state of affairs is not acceptable and would be considered abject failure in most industries.

This failure to change amounts to a padlock on opportunity for literally millions of Americans who are denied access to meaningful, high-quality learning and credentials. Ironically, not only do these individuals — especially first-generation and working adults — need higher education, the U.S. economy itself needs them to have the benefit of postsecondary education. So what’s wrong with this picture?

What’s wrong is that regardless of any religious affiliation, most colleges and universities in the United States operate as faith-based enterprises. That is, we are asked to take on faith that the model works — in the absence of any evidence that it does — and even in the face of abundant evidence it doesn’t. But some current practices are truly senseless. For example: nearly half of all students entering community colleges (and a fifth of college students overall) are funneled into “developmental” (i.e., remedial) education before they are allowed to take college-level courses.

Instead of pursuing their dreams, they are in effect rerouted back to high school education — and in some cases, elementary school. Students placed in the lowest-level developmental math course have virtually no likelihood of making it to graduation, and even better-prepared students “referred” to developmental ed often give up rather than persist. This is, of course, exactly the opposite of the intended effect.

Take another example: the lecture hall, which continues to be the primary forum for educating large groups of students. This approach reduces students to passive recipients of professional wisdom and strips them of agency as well as any responsibility for their own education. But we know passivity is death to learning: engagement in project-based and experiential learning is far more effective. It is just harder to evaluate with multiple-choice tests.

In other words, we short-change the development of competencies that citizens need and employers really seek, such as critical thinking and problem-solving, teamwork and leadership — in favor of content knowledge that can be easily tested and that soon is out of date. And computers do a far better job than humans of storing and retrieving information. Perhaps most seriously, we have limited ideas about what constitutes higher education, frontloading it all into a credential earned — at best — when we are still adolescents.

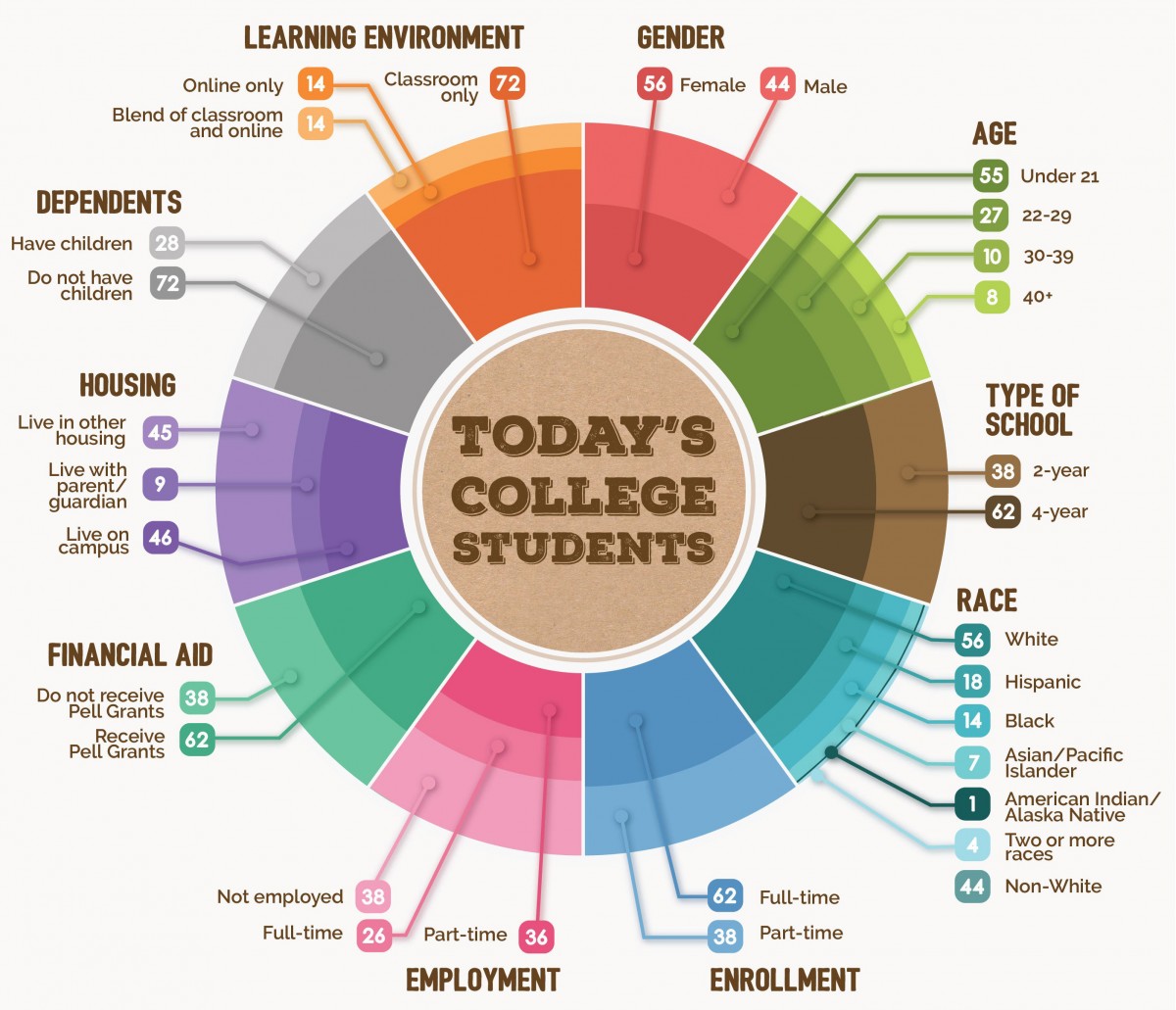

The reality is that most college students today do not conform to the college student stereotype, i.e., 18 to 22 years old, living on campus and studying full-time. Though we call them “non- traditional” students, they now make up more than half of the college body. Forty- five percent of all college students are 22 or older. Fifty-six percent live off campus. Nearly a third have children themselves.

Source: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

We not only ignore the reality of students’ actual lives, which require flexible scheduling and learning approaches appropriate for adults; we also ignore societal needs for continuous learning in the face of continuous change.

Continuous learning includes so-called “soft skills,” like nonverbal communication and leadership — competencies that employers find even more valuable than technical knowledge. This means we need to question the very premise that education should be about “knowing” at the expense of “doing” and the related elitism that pervades the basic assumptions of higher education: the idea that the goals of “employment” and “higher education” are somehow at odds.

But with the exception of clinical and technical jobs, most hiring managers don’t care about majors. What they care about is whether employers can write, present, think critically and apply knowledge to solve problems. And yet these are precisely the competencies we push to the side, preferring to bet that graduates will somehow magically acquire them in the course of their college experience.

To be clear, I am not advocating for a stripped down, narrowly instrumentalist curriculum, but instead the opposite. We need to create more opportunities for students to grapple with hard problems that are often informed by an understanding of how people have approached such problems in the past. Right now, most college graduates are not “grappling.” They’re writing a few papers (but not too many) and taking a lot of multiple-choice tests. And a lot of them cheat. They focus on passing the course and getting out of college. They’re not acquiring the powerful, enabling capabilities that will make them effective in the future whatever they do.

After graduation, there are rarely multiple-choice tests to take — but there will always be new and increasingly complex problems to solve. Why not reconceptualize higher education so that it genuinely equips people to thrive in an economy that demands the ability to adapt and learn? And that requires the ability to work with technology as well as a profound understanding of technology’s capabilities and limitations?

Reimagining higher education means confronting the reality of work and what it requires — and what it is likely to require going into the future. While the future is impossible to predict, we do know that it is likely to involve greater and smarter technology, especially artificial intelligence. What will it take to “robot-proof” our children so they are prepared to succeed in the future of work? Let’s begin by focusing education on those qualities that make us uniquely human.

Cathrael Kazin serves as managing partner of Volta Learning Group, which designs new learning and credentialing strategies for evolving industries. Much of her work centers on reimagining postsecondary education to prepare all individuals for the future of work. She also recently helped Education Design Lab develop a series of badges for 21st-century workplace skills, such as resilience and creative problem-solving.