“Are you a chaplain to the Empire, or are you a prophet of resistance?” said the Rev. Michael-Ray Mathews at the 10:45 a.m. Sunday morning, July 22, worship service in the Amphitheater. “Our prophetic resistance project is seeking to understand how faith and spirituality inform social and racial justice so we can cultivate the Beloved Community and disrupt the Empire.”

Mathews’ sermon title was “Resistance & Hope: The Spiritual Project of Organizing,” and his Scripture text was Ephesians 6:10-20, putting on the whole armor of God.

He began his sermon singing a psalm based on Psalm 19:14.

“Let the words of my mouth, bring you praise,” Mathews said. “May the words that I speak be seasoned with your love and grace. May the things, O Lord, that I choose to say bring glory, not shame, to your name this day. Let the words of my mouth bring you praise.”

It was during a workshop for clergy in 2014 that members of the Amos Project in Cincinnati used the question, “Are you a chaplain of the Empire or a prophet of resistance?” as an ice breaker.

“The ice melted real fast,” Mathews said. “The conversation was animated and agitated. As clergy, we reflected on the way we had been trained to be chaplains of the Empire.”

They struggled with what it would mean to be a prophet of resistance, to speak truth to the king and to the people.

“We were patting ourselves on the back for a couple of weeks about how good we felt, until we heard about Michael Brown in Ferguson,” Mathews said. “That question was turned into a haunting interrogation in the face of state-sanctioned violence.”

Mathews and his colleagues realized that they needed to create a space for clergy and all people of faith to resist the logic of the Empire. That logic, he said, is at work in our societal structures and narratives.

Theologian Howard Thurman posed a question in 1948: What does faith have to say to those who stand, in this moment in history, with their backs to the wall?

Mathews and others seek racial and social justice through trainings and blogs and use Thurman’s question to “strengthen and deepen the moral imperative across race, class and geography.”

There are interlocking issues — such as a living wage or the plight of immigrants or the formerly incarcerated — that need the moral courage that is sustained by deep relationships in order to be addressed.

“This is a spiritual project that demands our hearts, our souls and our lives,” Mathews said.

On a visit to the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, Mathews spent time looking at the exhibits of soil from sites where lynchings took place. He read the signs with the names of the locations, the dates, and, if possible, the name of the person.

“I was jolted by a flash of memory when the I saw the bright red soil of Henry County, Georgia,” he said.

Mathews’ family was from Henry County, and a man named Jesse Jefferson was lynched there in 1946.

“That was two years after my mother was born and the same year that my family left for Ohio. I wonder how their faith sustained them, these people with their backs to the wall, with terror driving them north and west,” he said.

Mathews asked how their faith sustained them in the Jim Crow South, as well as the “Mr. James Crow North,” where a more polite form of racism existed.

The Empire, said Mathews, is spread across people, places and time. It shapes how we live together, he told the congregation. It is based on a philosophy of hierarchy, scarcity and isolation.

“In this hierarchy, some lives matter more than others,” he said. “This hierarchy defines how we regard each other.”

Scarcity means that there are limits to our resources.

“Scarcity says there is not enough. I need more, and that is the way it is,” Mathews said.

Isolation is rooted in individualism and tribalism, dividing people from one another.

“The work of the prophet,” said Mathews, “is to move society from hierarchy to dignity, from scarcity to abundance and from isolation to human belonging.”

This work needs moral courage in order to engage the Empire, dismantle Jim Crow and stand with those who have their backs to the wall, he said.

Empire is relentless, he added.

“For every win in the movement, there is a force to undo it,” he said. “I lament as I watch our work being undone by the Empire. We are resurrecting language from the civil rights movement.”

Mathews was drawn to the “power analysis” of the apostle Paul, who said that the struggle was not against flesh and blood but “against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic power of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in heavenly places.”

People of faith and moral courage need to be relentless, too, he said. The spiritual aspect of the struggle is found in the “meaning-making junctions” that invite people to a space where the sacred is found.

These sacred junctions allow the re-imagining of the world. These junctions rely on the practices of prayer, psalm-making, art, dance, fellowship and study.

“These are the fuel for sacred resistance,” he said.

With forces aligned to undo the Beloved Community, it is clear that no one can stand alone.

“We have to be like manna in the desert for each other,” Mathews said.

His sermons this week will explore the Theology of Resistance and the movements of “Encounter,” “Disruption,” “Re-imagining” and “Prophetic Action.”

“If we are not cultivating our own moral imagination, we are probably living inside someone else’s,” he said.

Mathews said that in 2015, the language of white supremacy re-emerged in public conversation after decades on the margin. He was leading an interfaith workshop and wondered if he should use the text from Ephesians and decided to take that risk.

He defined white supremacy as a spiritual force that shaped how we see ourselves and others.

“It lives in our systems and our culture, clarifying who belongs,” he said.

Mathews expected some pushback on his definition of white supremacy, but was taken aback that the push came from the use of the words “spiritual force.”

The group, he said, felt that the term was too Christian and too irrational and they were not ready for it. His colleague stepped forward and said, “Wherever two or three are gathered … ” Mathews thought she would continue with a quote from Jesus.

But she said: “Wherever two or three are gathered, there is a collective consciousness.”

“That was a brilliant way to talk about white supremacy,” Mathews said.

The term collective consciousness was a way that group could understand the deep conversation about how to cultivate moral imagination.

“If we are not doing (creative re-imagining) together, we are living inside someone else’s imagination,” Mathews said. “The work of moral imagination is powerful enough to engage the powers and powerful enough to get us free.”

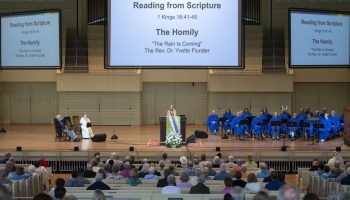

The Rt. Rev. V. Gene Robinson, vice president of religion and senior pastor, presided. Jennifer Jansen, who is head usher of the Amphitheater, project manager for performing and visual arts at Chautauqua, viola player with the Erie Philharmonic and a viola teacher, read the Scriptures. The hymn-anthem was “Love Divine, All Loves Excelling,” setting by Mack Wilberg. The Chautauqua Choir sang “Almighty Father” by Leonard Bernstein from Mass. The response after the morning prayers was “Return to God” by Marty Haugen. Peter Steinmetz served as cantor. The offertory anthem was “The Dream Isaiah Saw” by Glenn L. Rudolph, words by Thomas H. Troeger. The organ postlude was “Fugue on the Name of ALAIN, op.7” by Maurice Duruflé. Jared Jacobsen, organist and coordinator of worship and sacred music, directed the Chautauqua Choir. The Robert D. Campbell Memorial Chaplaincy provides support for this week’s services.