Cathal J. Nolan is a scholar of war.

His sweeping history of armed conflict, The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost, published by Oxford last year, has been hailed as radical re-examination of what war is all about, mainly by debunking the idea of the “decisive battle.”

“The common myth is that war is abnormal, but when you look at it, it’s pretty constant,” Nolan said. “People think that peace is the normal condition. I’m not convinced that it is.”

Nolan has explored the nature of war in 14 scholarly books and seven novels. He is frequently cited in historical TV shows. As an associate professor of history at Boston University and the executive director of the International History Institute there, he shares his deep expertise with his students. And he often uses war movies to pique their interest.

Nolan argues that his students, and young people in general, are an “acutely visual generation” who don’t read much, but love movies. What little sense of history they have, he said, is rooted primarily in films in which Hollywood “serves up fake history.” The films, he said, provoke interest in remote events and, ideally, steer students to books and debates for a deeper understanding.

At 3:30 p.m. Tuesday, Aug. 21, in the Hall of Philosophy, Nolan will talk about war movies in “Fake History: War and Hollywood,” as part of the Oliver Archives Heritage Lecture Series.

The movies get a lot wrong about war, but they get many things right, too, Nolan said. Hollywood does not shape public opinion as much as it is shaped by public opinion, reflecting social, political and cultural trends.

The movie industry embraced tales of war early, most notably with D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” in 1915, a racist epic that posits that the United States was really born as a country with the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction. The klansmen are portrayed as heroes.

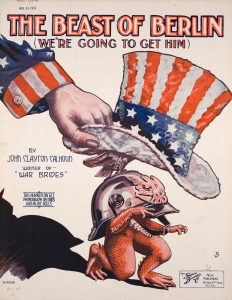

Heroes and villains have always loomed large in war movies, Nolan said. During World War I, Hollywood stoked patriotic sentiment with such pro-war films as “The Prussian Cur” and “The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin.” The good guys were really good, and the bad guys were pure evil.

Heroes and villains have always loomed large in war movies, Nolan said. During World War I, Hollywood stoked patriotic sentiment with such pro-war films as “The Prussian Cur” and “The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin.” The good guys were really good, and the bad guys were pure evil.

In the 1920s and ’30s, war became a passe subject, with movies reflecting the isolationist mood of the times, Nolan said. That changed as the world descended into World War II, with 1941’s “Sergeant York,” in which Gary Cooper plays the eponymous, laconic bumpkin who almost single-handedly defeats the Kaiser’s minions.

Morale-boosting pictures like “The Fighting Sullivans” and Frank Capra’s pseudo-documentary series, “Why We Fight,” followed. John Wayne, who sat out the war with a bad knee from playing football, became a big star in “Sands of Iwo Jima.” The Korean War inspired gritty portraits of men in combat like “Pork Chop Hill.”

Vietnam changed everything, Nolan said. John Wayne bombed in “The Green Berets.” American films turned from the heroic to the ironic with fare like “Catch-22,” “M.A.S.H.” and what Nolan calls “the astoundingly ahistorical” film “Kelly’s Heroes.”

“Hollywood was riding the wave of the counterculture,” he said.

“Apocalypse Now,” “The Deer Hunter” and “Coming Home” went further. They were not just anti-war but practically anti-veteran, he said. The bad guys were not so much the villainous enemy, but our own American leaders and military — if not America itself.

“In short, with its usual black-and-white moralism, but following rather than leading popular academic and cultural motifs, Hollywood flipped the script to relocate the evil in war,” Nolan said.

By the 1980s, though, the hero was back in “Uncommon Valor” and the “Rambo” movies, with the misunderstood veteran, bloodied but unbowed, returning to Vietnam to rescue captured Americans left behind.

By the 1980s, though, the hero was back in “Uncommon Valor” and the “Rambo” movies, with the misunderstood veteran, bloodied but unbowed, returning to Vietnam to rescue captured Americans left behind.

Then came 9/11 and a resurgence of patriotism. But, Nolan said, Hollywood again shifted its focus, depicting soldiers who fought and died for one another, instead of for some ideal or even one’s country. Private motivations superseded national goals, and the causes of war were unimportant compared with the virtues of the individual warrior, he said.

All the while, the horror and drama and glamour of war were plumbed in countless fantasy and science-fiction works, including the “Star Wars” and “Lord of the Rings” series and “Game of Thrones.” Nolan himself has written seven novels under the name Kali Altsoba in a character-driven series about war in the future called The Orion War.

Perhaps most notable, Nolan said, is the technological advances in both filmmaking and war-making that have allowed Hollywood to capture a fundamental aspect of battle that the Hebrews called “the lust of the eye” — battle as spectacle, a visceral, primal experience like no other.

“What Hollywood gets right is that war excites, especially young men,” Nolan said. “It fascinates like fire; moving, almost alive. Emotions are more intense. Its effects last for decades, not just with individual veterans, but with society as a whole. A significant minority of men love war. It’s the dirty secret we don’t talk about.”

And war remains a central, if not the central, aspect of the human condition, he said.

“Big wars like World War I and World War II were crescendos; they were not normal,” Nolan said. “What is normal is constant, chronic warfare, wars of empire maintenance, not just over years or decades, but multiple decades.”

Nolan sees little reason to be optimistic.

“We love war,” he said. “It’s an ugly, uncomfortable truth.”