A cure to the social and cultural ills of 21st-century American life lies within its people — at least, so says Wynton Marsalis.

A cure to the social and cultural ills of 21st-century American life lies within its people — at least, so says Wynton Marsalis.

The only catch? Each of us has to help find it.

“We’re ultimately responsible for the well-being and vision of our nation,” said Marsalis, a world-renowned trumpeter, composer and the artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. “There’s a lot of it to go around. If enough people think there shouldn’t be this type of prison population, there won’t be. If enough people think there shouldn’t be housing discrimination, there won’t be. And no one person is going to decide that.”

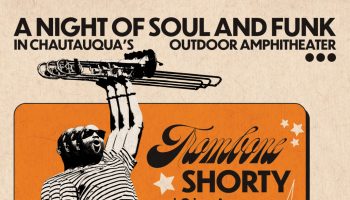

At 10:45 a.m. today in the Amphitheater, Marsalis will close Week Nine discussions on the state of race and culture in the United States as part of a panel that includes Iliff School of Theology’s Miguel A. De La Torre and Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture Curator of Latinx Studies Ariana A. Curtis. Robert Franklin, president emeritus of Morehouse College and former director of religion at Chautauqua Institution, will moderate.

“With Robert as our guide, we want to unpack Thursday night’s (‘Ever Fonky Lowdown’) performance with Wynton, but also hear reflections on the performance — and the week — from two of our other contributors to the weeklong examination of race and culture in America,” said Matt Ewalt, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education. “As we close our week, and our summer assembly season, we also want to consider what work and conversations we carry with us as we return to our home communities.”

Marsalis considers the music and tradition of jazz to be inextricably linked with the national conversations on race that have happened throughout U.S. history.

“The music was a cause,” he said. “People like Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, and later Duke Ellington and Fats Waller, that generation of musicians, they knew it was a cause. And the white musicians who played knew it was a cause, too. Bix Beiderbecke knew it was a cause.”

According to Marsalis, early 19th-century jazz clarinetist Benny Goodman was another particularly significant example of a white musician who advocated for racial justice.

In 1936, Goodman hired pianist Teddy Wilson as a member of his group, one of the first times a black musician performed onstage with a white band.

“Even white people had a consciousness about it,” Marsalis said. “Now that’s decreased as the time has passed, because white consciousness has basically gone away in jazz. But it used to be there.”

Nowadays, white jazz musicians don’t advocate enough for racial justice, according to Marsalis.

“Who’s a white jazz musician today that’s really conscious of civil rights and a champion of them like Dave Brubeck was, or Benny Goodman?” he asked. “Name them, and what is their body of work?”

But the real question, the one Marsalis said he’s been asking himself since the 1980s, is why that development has taken place in music that has its own roots in slavery.

“There’s a reality out here of apathy,” he said. “Why? I don’t know. I’m not indicting people because they’re not (a champion of civil rights), I’m just saying there’s a paucity of figures.”

Claims of ownership over jazz — and music in general — are false when they are based on race, Marsalis said.

“Black and white are constructs for America, and we use them because it helps us negotiate what it is,” he said. “But music is beyond that. I would not relegate our racial problems to our music. John Coltrane said that in the book Black Nationalism and the Revolution in Music by (Frank) Kofsky. I read that in the ’70s, and I thought, ‘Damn, they put Trane on the cover of this, and he’s refuting the premise of the book.’ ”

For Marsalis, jazz is about joy. about things coming together — a process that he compared to the experience of a kid asking if they can play basketball with local players.

“After you start scoring baskets, (the players) are like, ‘Oh, shit, this is my man,’ ” he said. “Based on your ability to play, now your relationship with them has changed. You don’t even know the guys. Well, there you go, that’s jazz. It’s very natural. Nobody’s hanging up a sign, there’s no philosophers out there. If you know the rules, you can play.”