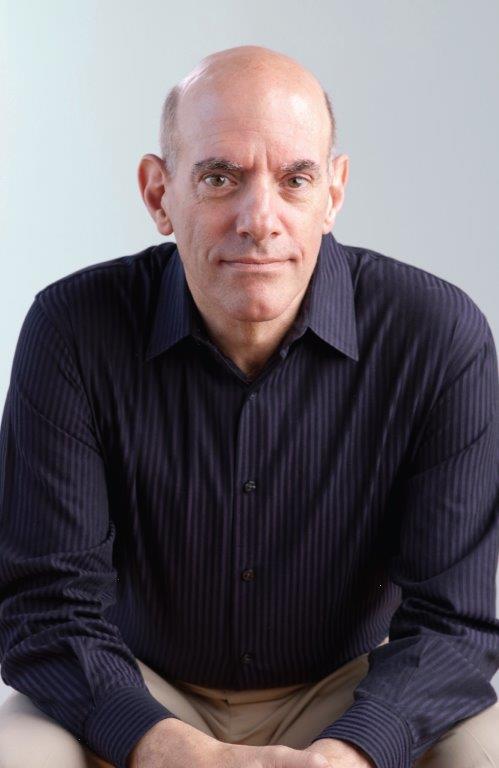

With a three-step plan for reflection and reclaiming the definition of reality and the Divine, One River Foundation Co-Director Rabbi Rami Shapiro plans to enlighten his Chautauqua audience through his experiences and research on religion and spirituality.

Shapiro will give his lecture, titled “Seeing the Face of God in the Shadow of Our Dark Night,” at 2 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 4 in the Hall of Philosophy to continue Week Six of the Interfaith Lecture Series, “Embracing the Dark: Fertile Soul Time.”

He will first broadly look at the nature of reality to convey the point that people are all part of something bigger, known as God and the Divine.

“(My) second point is that we really never know how far in we are,” Shapiro said. “We are definitely in a very dark night of human civilization … a crucifixion of the human ego, brought about by the ego, by our greed, our fears, prejudices.”

He said he wants to emphasize how much of a downward spiral the world is in — economically, politically, biologically and environmentally.

The third part of his lecture will ask “How do we get out?” by returning full-circle to his first point of manifesting God.

“The way we get out is to reclaim that knowledge, in a very existential way, that we viscerally experience the Divine itself,” Shapiro said.

The One River Foundation is a 501(c)(3) educational organization dedicated to teaching Perennial Wisdom, also known as a philosophical perspective of dealing with reality, being and emphasizing mysticism.

Perennial Wisdom is considered the fourfold truth at the heart of religion: Everything is a manifestation of God; humans have a capacity to know Him directly through various contemplative practices; people can only engage with others according to the Golden Rule; and awakening to realize someone’s true nature with the Divine is the premise of engagement with compassion and justice.

Manifesting the Spirit and the Divine allows the fear, bias, madness — and everything else destroying human civilization — to come to a pause, Shapiro said. These things need to happen concurrently to allow the bad to absorb the good and become whole again.

“When you see that, you uniquely feel connected to (and) responsible for compassion,” Shapiro said. “Everything becomes an expression of God.”

He said he wants his audience to understand how dire the current situation the world is in, and how everyone has the individual ability to transform the situation if they’re willing to put the work in.

“We have the spiritual capacity to change the dynamic of the dark night so that it becomes a time of renaissance, a time of rebirth,” Shapiro said.

Shapiro first experienced divinity at 16, and has been consumed by this experience ever since.

“It totally defined my life,” he said. “For decades, I have been motivated by that experience, and I’ve had that experience over and over again.”

At the time, Shapiro was studying Zen Buddhism and learning how to meditate. He was sitting on the shore of a lake in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, meditating alone, “when that self, my ego, simply disappeared.” It was essentially an out-of-body experience for Shapiro.

“I don’t know what happened while I was gone, because I wasn’t there, right? Rami was just emptied out and disappeared, gone to — I don’t know what to call it,” Shapiro said. “But when I came back into my normal, waking-state consciousness, I was acutely and definitively aware of everything. I felt this enormous love from everything, and for everything.”

Interpreting this through hindsight, Shapiro said he believes he somehow “tapped into the oneness,” of everything — and simultaneously nothing — around him.

“(I was) called to share that insight, which is not unique to me by any means,” he said.

Although this experience relates specifically to Zen Buddhism, Shapiro said every mystic tradition has similar teachings, all with insight and practices designed to awaken people to this wisdom.

“The fundamental thing I’m trying to accomplish is to help people realize who they think they are,” Shapiro said. “You’re actually the universe becoming conscious of itself, or God becoming conscious of itself. That’s what I’m trying to get across: That you are not who you think you are … and we should act accordingly.”