Both the Smith Memorial Library, which stands like a bookend on Bestor Plaza, and Smith Wilkes Hall, the home of the Bird, Tree & Garden Club, bear the name of Addie Mae Smith Wilkes, the philanthropist who funded their construction.

The library and BTG have been linked in this way since their physical spaces were dedicated in 1924 and 1931, respectively. As proponents of learning, their missions are similar. And this week, the two groups converged paths once again when BTG donated eight books on trees to the library.

The books were donated by Bob McClure in memory of his wife, Sally, a dedicated BTG member and officer, who died in 2014.

The tree theme was inspired by last year’s celebration of the 100th anniversary of the dedication of Chautauqua’s Arboretum.

“We have had the year of the tree,” said BTG President Angela James. “We’ve had tree talks, tours of the Arboretum, and this is kind of like our capstone.”

The donation includes fiction, nonfiction, adult and children’s selections. The books were researched by BTG member Jennifer Francois. She reached out to friends in the environmental industry and garden clubs near her off-season home. She also took to Amazon.

“A lot of times, one interesting title would lead you to another and just build quite a long list of children’s books, adult reference books and fictional books,” she said.

Francois and library director Scott Ekstrom compared their lists of possible selections and figured out which books already existed in the library system.

“These are all (donated) books that we do not have in the Chautauqua-Cattaraugus Library System at all, so these books will be shared with 37 other libraries,” Ekstrom said.

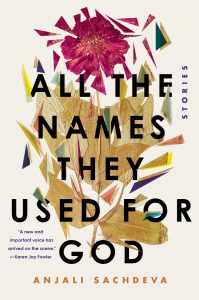

Titles include Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness, by Qing Li; Witness Tree: Seasons of Change with a Century-Old Oak, by Lynda V. Mapes; the reference guide Trees of Pennsylvania; and the children’s book The Magic and Mystery of Trees, by Claire McElfatrick and Jen Green. A few BTG members met Ekstrom last Tuesday to present the books to him.

“It’s a great way to add to our collection with their expertise and generosity,” Ekstrom said.

BTG has donated books to the library periodically for decades. Ekstrom said the stacks contain donated books from the BTG with nameplates that date back to the 1970s.

“It’s our intention over the winter to come up with titles focused on children’s books … (about) birds, trees and gardens and the general mission of the club, environmental awareness and conservation,” Francois told Ekstrom. “Hopefully, next year, you’ll have another collection.”