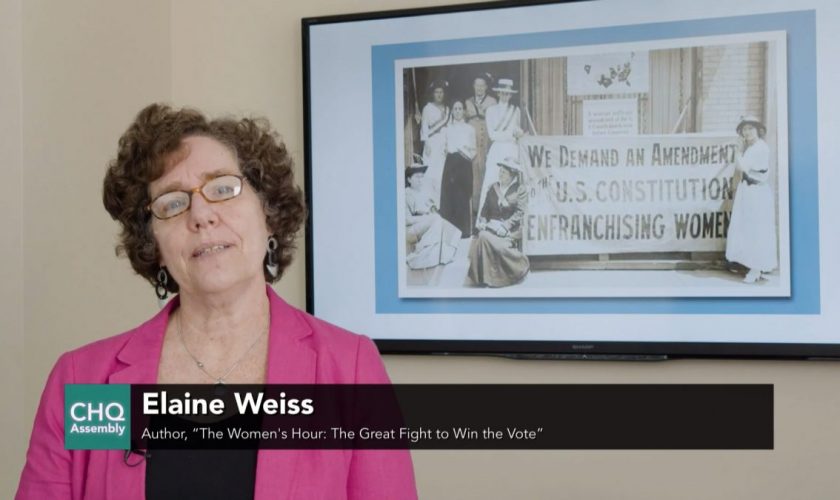

The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment, guaranteeing and protecting women’s constitutional right to vote.

The year 2020 is also the year in which a groundbreaking news publication, The 19th, was born, aptly named for its one of its main focal points: the intersection of gender and politics.

Co-founder Errin Haines told the story of The 19th during her lecture, “The Role of Journalism and Media at the Intersection of Gender, Politics & Policy,” which she presented at 10:45 a.m. EDT on Wednesday, July 29, on CHQ Assembly Video Platform, as part of the Week Five theme for the Chautauqua Lecture Series, “The Women’s Vote Centennial and Beyond.” Due to technical issues, Haines’ lecture will not be reposted to the CHQ Assembly Video Platform, but will be reproduced as an episode of the Institution’s CHQ&A podcast.

During her lecture, Haines not only elaborated on the founding of The 19th but also discussed the role of journalism in the discourse surrounding race and gender in politics and elections, specifically the role played by The 19th.

“Race and gender were not just a story of the 2020 election, they’re the story of the 2020 election,” Haines said. She said the online publication began to take shape following the 2016 presidential election, the media coverage of which Haines and The 19th co-founder Emily Ramshaw found very frustrating.

“The majority of the political writers were white men,” Haines said. “We realized newsrooms needed to be more inclusive.”

With the acknowledgment of the stunning lack of diversity in newsrooms and political journalism across the country, thus began the quest to build an outlet that represented the electorate and was a safe and equitable space for women and people of color.

Over half of the United States population identify as female — a statistic that is not paralleled in governmental offices or in newsrooms reporting on these offices. However, though female representation in office and in journalism is lacking, the representation for people of color, specifically women of color is even smaller.

Historically, women of color have been disproportionately underrepresented at the ballots. The 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment, intended to guarantee a right to vote regardless of sex, did nothing to dissolve the Jim Crow laws enforcing race-based voter suppression throughout the Southern United States for many years. This asymmetric distribution of voting rights is the reason behind the inclusion of an asterisk in The 19th’s website logo, meant to symbolize a recognition of the omission of women of color from the ballot.

The 19th launched on Jan. 27, 2020, right in time for the Iowa caucus. Political journalists across the country were poised and ready to jump on the presidential campaign trail, which Haines referred to as “our Super Bowl.”

Then, COVID-19 swept through the world, leaving in its wake national shutdowns and transforming the physical aspect of the 2020 campaign trail into a ghost town of solely virtual coverage.

“It was not really the start we envisioned, but we still have an important role to play,” Haines said. “Women are disproportionately affected by the pandemic and are sitting at the intersection of so many things.”

Haines was prepared to report on the presidential race but soon realized a new topic had taken precedent.

“The other pandemic of systemic racism reared its head with the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor,” Haines said. It was at that point that she realized the need for open and extensive coverage of the intersection of politics, gender and race. “When we talked about what we produce in our newsroom, it was a vision that was very long overdue and very important in this moment.”

One unique element of The 19th is that it is free and all-access, free to reprint — making it one of the few national-scale news outlets not hidden behind a paywall.

“We are seeking to democratize journalism for the majority of the electorate; making our news free to consume and free to republish means that you have women — and especially women of marginalized communities, who may not be reading the news on paid sites — being able to access our news,” Haines said. “It is not as important to us that they know it’s The 19th’s stories as it is that they are getting our journalism.”

The hope that Haines has is that The 19th will open new avenues for political participation, specifically for those who may have felt left out of the discourse.

“We encounter so many women who want to have those conversations, but don’t necessarily have the vehicle to start them in the communities where they live,” Haines said. “We can be that bridge.”

Another unique facet of The 19th is its lack of an opinion or editorial section, something Haines said was done intentionally to avoid ostracizing those who may share different beliefs.

“We decided not to have an opinion or editorial section in order to build faith with our readership through reporting and through facts,” Haines said. “We want to encourage a community; we seek to be a home for all women regardless of their political strife. We want people to feel welcome.”

When asked by moderator Vice President and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education Matt Ewalt about the role that men play in her reporting, Haines assured viewers that no one was excluded, saying that “men are absolutely part of this conversation. Frankly, we couldn’t be covering the 2020 election if we were not covering men.”

However, she wanted to emphasize that the purpose of The 19th was to elevate the role of female journalists in an atmosphere where there is less representation, citing the fact that over two-thirds of political journalists are men.

“Women are as qualified and capable of weighing in on our politics and of shaping the conversation around our politics as men are,” Haines said.

“As editor-at-large, I have the role I wanted to play, not only as one of the first reporters, but also as an ambassador,” Haines said regarding her appearances on and in various news platforms, including NPR and PBS. “This is an opportunity to be among these visionaries not fixing a culture, but building a culture.”

Haines went into the creation of The 19th with a goal of creating an inclusive environment.

“You have to create the climate for women and minority journalists to thrive, to do the kind of journalism that is going to be impactful, that is going to afflict the comfortable, that is going to right wrongs and that is going to move us to a more free and fair democracy,” she said.

As the United States continues to battle COVID-19, Haines believes that political journalism is more important than ever.

“The pandemic is absolutely political,” Haines said. “With the pandemic, it is our duty to inform women of how they can safely and fully participate in this democracy.”

As the 2020 election draws closer, many issues are appearing in the forefront of the media, forcing many people who may have been previously isolated from engagement to involve themselves in politics.

“This national reckoning has really presented an opportunity for people to learn and expand their worldview,” Haines said, calling it “very encouraging.”

One concern that Haines hopes to dispel with The 19th’s bias-avoidance publication style is the creation of yet another echo chamber where people simply surround themselves with like-minded thinkers and close themselves off to new thoughts and opinions.

“Our timelines are filled with people who think like we think,” Haines said. “We have to be more deliberate about expanding that circle.”

Haines has been inspired by the shift of race and gender issues to the forefront of public concern, and is adamant that journalism must continue to play a large role in the dissemination of factual reporting.

“This country was founded on protests and dissent and revolution,” Haines said. “Journalism has the potential to be part of that ongoing revolution in our country that helps to perfect our union.”

As systemic injustices are more widely recognized, Haines is hopeful that the dissolution of historically biased institutions and ways of thinking will allow a space to build unity.

“The important conversations that we have now are about the centennial of the suffrage movement and what voting means and who gets to participate in this democracy,” Haines said. “These are the big questions that we have an opportunity to wrestle with, hopefully with the goal of finding a new way forward together.”