“How do we hold joy and pain together in a world that forces us to hold love and suffering, grief and celebration?” asked Rabbi Sharon Brous at the 9:15 a.m. Ecumenical Worship Service Monday in the Amphitheater. Her text was Deuteronomy 21:1-8, and the title of her sermon was “From the Real to the Ideal.”

“How do we hold joy and pain together in a world that forces us to hold love and suffering, grief and celebration?” asked Rabbi Sharon Brous at the 9:15 a.m. Ecumenical Worship Service Monday in the Amphitheater. Her text was Deuteronomy 21:1-8, and the title of her sermon was “From the Real to the Ideal.”

Brous said her sermon would be a hard one but “there is always a word of hope at the end of a hard talk.” Her daughter celebrated her Bat Mitzvah in May, a joyous occasion the family had planned for all her life. One week before that celebration, a shooting took place at Chabad of Poway near San Diego.

“Lori Gilbert-Kaye died, and there would have been more deaths, but in California the shooter could not use a magazine clip,” Brous said.

This tragedy took place six months after the shootings at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, and several weeks after the shooting at a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand. Brous added that few people have forgotten the shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, or the Sikh Temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin.

“We are seeing a terrifying new reality — the rise of anti-Semitism in the United States,” Brous said. “People in Orlando and San Bernardino took pledges to the Islamic State. These shootings were done by people who thought they were doing the will of God. They showed their love of God by killing people.”

The hallmark of religion in the 21st century is religious violence, violence in holy places, that makes a “mockery of the tradition.”

There are people who want to “start a race war, or believe that Jews are trying to infect us with asylum seekers or who forget that Muslims have been here since the beginning. Religion is being used as a justification for racism, anti-Semitism and Islamophobia,” Brous said.

The irony, she said, is that religion is a force for love and justice. Religion is in crisis, especially as religion is decoupled from kindness.

Brous turns to the sacred texts to make sense of the world and said that Deuteronomy 21:1-8 “could be a model for us.”

In the text, a man is found dead in a field and no one knows the culprit. The elders and judges of the surrounding towns are called upon to step forward because no one just dies in the wilderness; the leaders are responsible. They measure the distance to each city and the one closest to the body is responsible. These elders and judges must take a young heifer to a ravine near the body and offer it as a sacrifice.

The priests come to offer a blessing as the elders and judges wash their hands over the heifer and say: “Our hands did not shed this blood, nor were we witnesses to it. Absolve, O Lord, your people Israel, whom you redeemed; do not let the guilt of innocent blood remain in the midst of our people Israel.” They are then released from the blood-guilt.

“The rabbis asked ‘what does this mean?’ Are they really responsible?” Brous said. Her answer was yes.

The man was found dead because he did not ask for help so he was ignored. He was allowed to leave town without food or an escort. If the elders had been awake, he would be alive. So it is on us, the rabbis said, to cultivate a culture that sees the stranger and does not wait to be asked to give help.

Brous noted when she and her family arrived at Chautauqua, their hosts welcomed them and said, “This house is your house; our food is your food.”

“This is radical hospitality to a stranger,” Brous said. “This act of grace welcomed us. It has been done for you and you have done it for others.”

The City of Los Angeles has a program called “Safe Parking” to help homeless families who are living in cars. Churches, synagogues and mosques are asked to let these families live in their parking lots when they are not using them.

IKAR, Brous’ religious community, recently bought a plot of land that they will develop but are using as an event space. On the first night of Passover, they invited 10 homeless families who were living there to join them for the Seder. Some came in, and IKAR brought food out to others.

One woman called to Brous and asked if she had matzah. Brous looked astounded and then the woman said, “I am a Jew.” Brous told the woman that she and her daughter must come in and they celebrated with the IKAR community. “I felt my dignity being restored,” the woman said.

“We have to go out into the streets and see those who don’t ask for help,” Brous said. “It is on us if we don’t and something happens. We have to build a society that is counter-Egypt and counter invisibility. Our religion is rooted in love and justice, radical hospitality and radical empathy. If it is not, then it is on you and me.”

How do we hold the tension between our ideals and the reality we live in, when the real is more normative in this country, she asked.

Brous told a story from the Talmud of two priests running to the temple, in a competition to see who could make his sacrifice first. The one who was a little behind pulled out his knife to kill his sacrifice, but stabbed his competitor instead.

People stood around watching the man in pain. Rabbi Zadok said to the crowd to remember the text from Deuteronomy and asked who is responsible — only the priests addicted to their religiosity or all of us?

But the story does not end there. The father of man who was stabbed comes up and pulls the knife out of his son and says everything is alright. “The knife is still pure because my son did not die,” the father says.

“There are cultures of cruelty that develop right under our noses,” Brous said. “This story is a polemic against forgetting the sanctity of human life.”

Our job, she said, is holy excavation. Every religion starts with a mystical event or insight that erupts like lava flowing down a volcano. When it reaches the bottom of the volcano, it looks like rock.

“Beneath that rock is the vital force of life, Brous said. We have to chip away to find the beauty, love and fervor that drove our ancestors.”

Chautauqua is a place where we can touch something holy and pure and experience the spirit of the ideal, she told the congregation.

“We can see love, not hate; forgiveness, not revenge; possibility, not despair,” Brous said. “We can seek the holy work in the redemption of the world.”

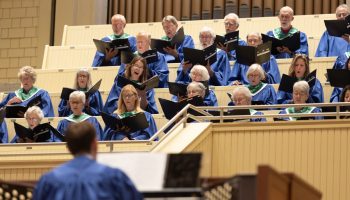

The Rt. Rev. V. Gene Robinson, vice president of religion and senior pastor, presided. The Rev. George Wirth, senior pastor emeritus of First Presbyterian Church, Atlanta, and a consultant for the Cousins Foundation of Atlanta, read the scripture. Under the direction of Jared Jacobsen, organist and coordinator of worship and sacred music, the Chautauqua Choir sang “With a Voice of Singing,” by Martin Shaw. The Edmunde E. Robb-Walter C. Shaw Fund provides support for this week’s services.