Susie Anderson

Staff Writer

Popular history says that Sacajawea died at 24. But Native histories, including that of the Bitterroot Salish, tell of her living into her 80s, spotted in places such as St. Louis and beyond. Author Debra Magpie Earling believes that an early death helps Sacajewea’s myth live on.

“Had Sacajewea lived and had they interviewed her, maybe the mythology would not have been as potent and powerful,” Earling said. “Had she had a voice in the story, I think she would have uncovered some things that were not so heroic in the journey.”

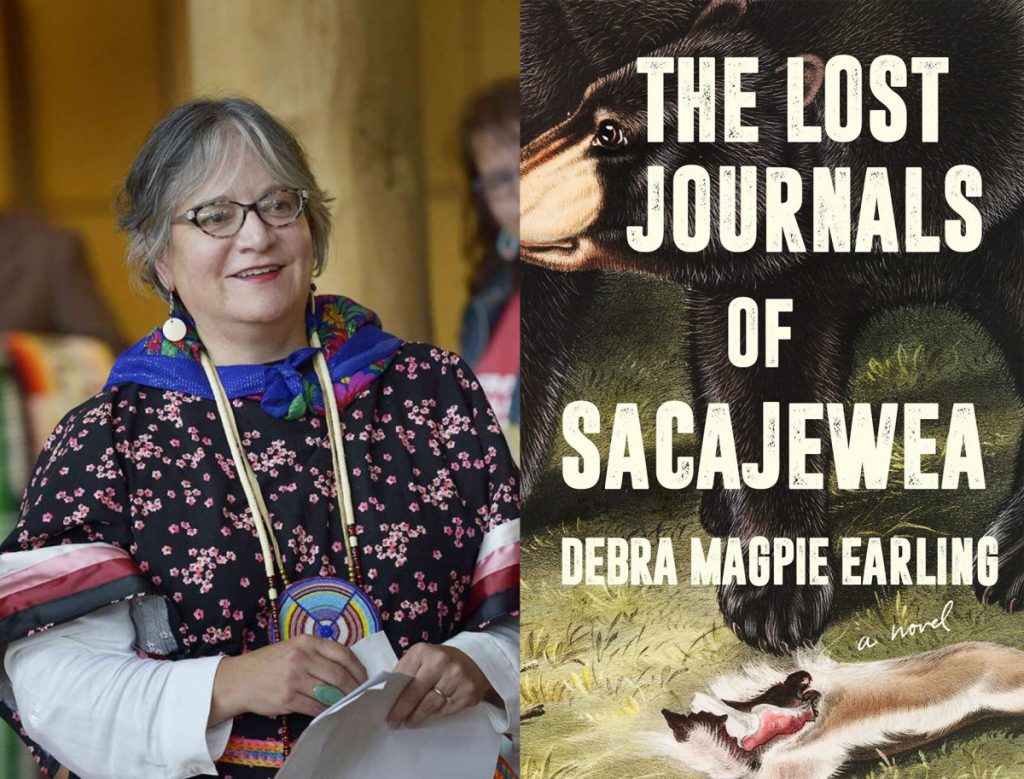

In a visionary work of historical fiction, Earling blends lyrical prose with particular punctuation to craft a voice of the mythologized guide and translator for Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery. At 3:30 p.m. today in the Hall of Philosophy, Debra Magpie Earling will present The Lost Journals of Sacajewea: A Novel for the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle.

In Earling’s novel, after Sacajewea’s village is raided, she is kidnapped and gambled away by French Canadian trapper Toussaint Charbonneau. While protecting herself and her newborn son, Sacajewea must learn how to survive across new terrain with

the white man who owns her and a group of explorers commodifying the land she loves.

The Lost Journals of Sacajewea is the most recent novel from Earling, who has received the Western Writers Association Spur Award for Best Novel of the West in 2003 and the Mountain and Plains Bookseller Association Award and the American Book Award, among others, for her debut novel Perma Red. She is a member of the Bitterroot Salish and currently an associate professor in the English department of the University of Montana in Missoula.

The impetus for the story emerged when Earling was asked to contribute to an anthology of essays surrounding the exploration of Lewis and Clark from Native perspectives with the esteemed historian Alvin M. Josephy Jr.

In the research process, Earling encountered a narrative of a Corps of Discovery member who gave away his wife to a sergeant for the night.

“The next morning, they find her brutalized, stabbed and beaten. She is by the interpreters’ campfire, and I thought, ‘Well, that wouldn’t have been (Touisannt Charboneau), it would have been Sacajewea — there she is (comforting the woman),’ ” Earling said.

Integral to the expedition yet an invisible undercurrent in many of the records, Sacajewea emerged as a story untold for Earling, who found herself intrigued to investigate what else was missing from the popular narrative of Sacajewea’s life.

“From the moment she appears, she is present throughout the rest of the journey and that shows, in some ways, how history makes women invisible and how it is important to sit with the women that have been historicized and look at their story,” Earling said.

Recentering Sacajewea in the historical narrative, Earling was conscious of her use of language. Among the many perpetuated myths of her life, Sacajewea’s supposed lack of knowledge of English and French was one that Earling wanted to counter.

“She is so learned in so many things and knew how to take care of herself, and I thought, ‘There is just no way that if she could speak Hidatsa, Mandan and Shoshone that she wouldn’t pick up immediately on other languages,’ ” Earling said. “So, I think that’s a real disservice to her intelligence.”

While writing from an Indigenous perspective in the language of English, Earling played with style to translate Sacajewea’s emotions and reverence toward particular objects, themes or people through capitalization, faded print and a mixture of prose and poetry.

“As she grows in her own understanding, her own perception of things begins to change,” Earling said. “I thought, ‘How could I make that work? How could I make that visible in the text itself and make it almost like a braille or another way of seeing within the story?’ ”

In addition to Earling considering the presentation of language, the vivid rehabilitation of the mythologized historical figure involved a care for the environment that informed Sacajewea’s experiences.

“It was really important to me to pay attention not only to the human language, but the ways in which Native people have long survived by paying attention to the world that surrounds them — and everything is important,” Earling said.

Through dreamlike prose, Earling immerses the reader into Sacajewea’s perspective, witnessing new people and terrain alongside the guide.

“I kind of throw readers into her world, but not without having handholds to make their descent,” Earling said, “and the handholds are cultural handholds — an attentiveness to the world around you that makes it survivable.”

In a week reflecting on the past informing the present, Earling highlighted how Sacajewea was one of the first Stolen Sisters, or missing or murdered Indigenous women. For Earling, centering Sacajewea in the historical narrative not only prompts discourse of women’s role in history, but also their role in the present.

“I think of her as a conduit toward understanding and toward peace,” Earling said. “So she’s very important, not only as a historical figure, but a figure that I believe all women can embrace and be held up by.”