So first, about that title.

In the Next Room (or the vibrator play) opened Saturday night at Chautauqua Theater Company. Contrary to rumors going around the grounds, the parenthetical expression is not an alternative title used when Sarah Ruhl’s play is produced at urban theaters more edgy than the century-old Bratton Theater. In the Next Room (or the vibrator play) is the actual name of the play, and it has been ever since it premiered at California’s Berkeley Repertory Theatre in 2009.

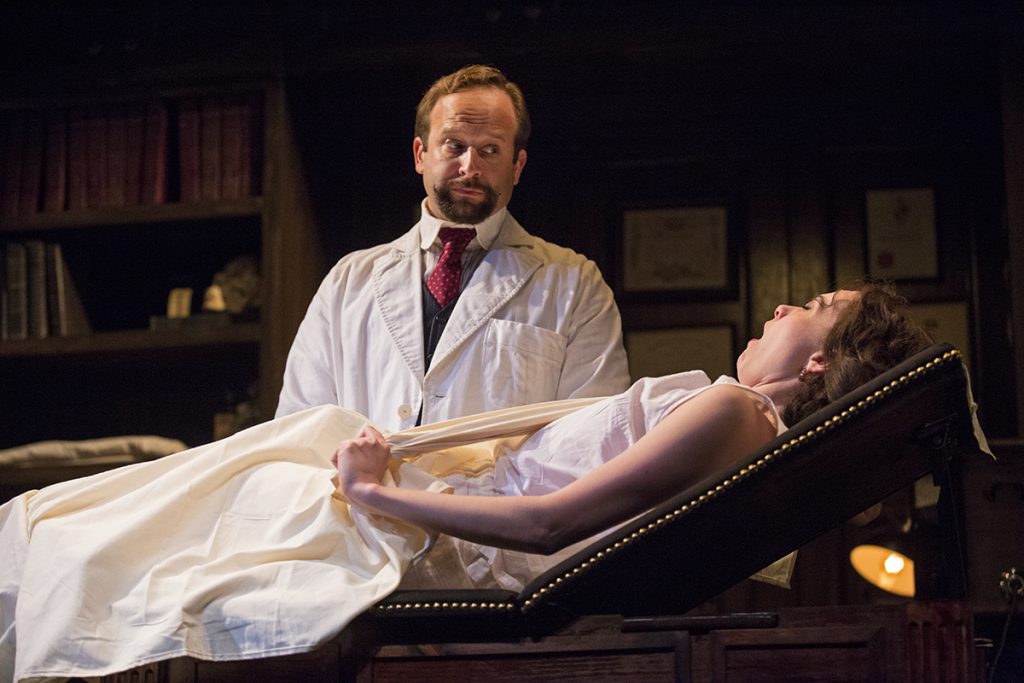

Now that we’ve cleared that up, we can praise this precise, well-acted production of In the Next Room as a excellent, good old-fashioned parlor drama. Set in the 1880s, the play is Ruhl’s thoroughly researched but fictional account of a Victorian gynecologist who specializes in treating so-called “hysteria.” Distraught ladies who enter through the onstage living room are ushered into his office, seated on a monstrosity of an ancient operating table, complete with stirrups, and “treated” with early-prototype vibrators.

The play’s most uproarious moments come when guest actor Adam J. Smith, as Dr. Givings, brandishes his tools, which resemble something like a cross between a power drill, a dildo and a KitchenAid mixer. There is nothing scintillating about those scenes, and that’s The Vibrator Play’s genius.

Larissa Kokernot — a Los Angeles-based director making her Chautauqua debut — has helmed a rather conservative staging. The whole production has the look and feel of a classic by George Bernard Shaw. The ladies wear full skirts and bustles and faux-ivory brooches. Alexis Distler designed the two-room set. In her preface, Ruhl suggests decorating the stage with “sumptuous rugs, sumptuous wallpaper.” Distler’s distracting lattice of woodwork and green-striped wallpaper are a bit overly ornate and grim; it’s hard to imagine that the bubbly Mrs. Givings (Kathryn Metzger) decorated the place.

In the Next Room can be effectively staged as a sort of stylized Victorian cartoon. What Kokernot has done is hyperrealist, which works with the exception of the last scene (more on that in a bit) and could be more effective in a higher-budget production. Thomas Edison is often invoked as an unseen additional character — “a great American!” — and we soon learn that Dr. Givings’ experiments with vibrators stem from his fascination with electricity, not sexual prurience. Despite Chautauqua’s Edison connection, the CTC props and tech departments faced a challenge in mounting the lighting Ruhl prescribes. Switches are turned on and off by characters who, in the words of patient Mrs. Daldry (Allison Altman), are beginning to imagine “a time when all will be electric, all will be plugged in.” She goes on to wonder, “Why will it not stop at lights, but the way we cook our eggs, and the way we get our chickens to lay their eggs, too?”

Altman, and most others in the cast, utter tongue-in-cheek lines like that in a style that is just over the top, but uniformly so. Five-time Tony nominee Laura Benanti played the role of Mrs. Givings on Broadway, which is easy to imagine given Altman’s effective comic timing and statuesque brunette bearing. She and her four conservatory colleagues actually acquit themselves better then the two guests actors, who have the unfortunate task of playing inattentive husbands.

This Vibrator Play may look like Shaw, but the plotline is Chekhovian, and based on pseudo-science that dates to the time of Shakespeare. Like Uncle Vanya, A Month in the Country and similarly moody Russian dramas, pretty much everyone onstage is infatuated with the wrong person, and the second act is devoted to unhooking a chain of unrequited lovers. Edmund Donovan is extremely amusing as Leo Irving, a wealthy young painter suffering from a “rare” case of male hysteria. The latest subject of his portraiture — and affections — is the Givings’ wet nurse, Elizabeth, (Margaret Odette) a free black woman who has a better head on her shoulders than the characters with money for lightbulbs, and the only marriage with no need for an electric vibrator.

The idea that women can suffer from some sort of “hysteria,” which can be cured by expelling excess fluid in the womb dates to early modern times; when Ophelia drowns herself in Hamlet, she’s supposedly suffering from green sickness, which is more or less the same bogus thing. Kokernot has described In the Next Room as a play with a feminist streak, but not a feminist play, and that’s exactly the right approach. That these women are constrained by both society and too-tight corsets is never in doubt, but Ruhl’s point is not to grind axes against white male patriarchs of the past. Her plays often veer off into magical realism and even science fiction, and the ending of In the Next Room does come with a whimsical twist. Theaters with larger stages and more money can probably better enact this big reveal, which involves nudity and bringing the action outdoors, into the natural light.

In the Bratton Theater, strategically placed ottomans and footstools block most viewers from seeing anything they might find untoward. And the resolution of the story is remarkably old-fashioned and chaste: a happy husband and wife can find love from each other, and cry out to God when they do.

Rebecca J. Ritzel is the performing arts columnist for The Washington Post. She teaches writing at the University of Maryland, and has a master’s degree in arts journalism from Syracuse University.