Review by Tom Di Nardo

Voltaire’s visionary Candide, or Optimism turned out to be an ideal demonstration of the talents, imagination, and resources of the Chautauqua Opera Company. This writer has seen four other productions of Candide, most more elaborate, glitzy or operatic, and a few with famous singers, but this one seemed to fit the powerful premise more organically. All the delicious songs are included, with this version allowing us to buy into the ridiculously improbable coincidences through constant motion and a willingness to emphasize the show’s glorious excess.

The 40-piece orchestra was placed behind the raked stage, with projections above them and sung titles shown on both sides. General and Artistic Director Steven Osgood began the show by mentioning the new lighting structure above the stage and air conditioning (eliciting early applause) in Norton Hall. Before taking the podium to conduct the “Overture,” now one of the most common program openers in orchestral literature, he warned that some of the cynical barbs might just project in our direction.

Bernstein was shrewd in choosing the 1759 classic Candide, a much more complex narrative than West Side Story. Voltaire had taken cynical aim at religion, war, greed, lechery, territorial invasions and the cruel side of human nature, addressing those then-commonplace realities by giving them an original, satiric slant. But George S. Kaufman’s truism that “satire is what closes on Saturday night” meant that the story had to be dressed up with rich, rhythmically surprising music, bawdy humor to balance the constant crises and witty lyrics that would make us look at ourselves as participants in the universal human fabric.

Many of the lyrics are so brilliant and downright funny that they often elicited guesswork at which of the many lyricists were responsible. Often, though, many of the spoken words did not come through clearly, at least into the Norton balcony, especially with orchestral background.

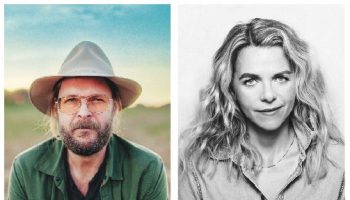

Robert Orth demonstrated his stage skills both as the narrator Voltaire and Dr. Pangloss, who keeps popping up to insist that every catastrophe, shipwreck, robbery, earthquake and even his eventual syphilis has some justifiably positive result.

In a lovely touch, John Reisen (the constantly wide-eyed Candide) and Rebekah Howell (his beloved Cunegonde) met here as Chautauqua Opera Young Artists four years ago, returning now to star. Their first serious intention strikes an immediate reality for us — their rose-colored glasses about marriage hinder each one from hearing his dreams of a humble rural life, and hers of opulent luxury.

Curiously, the title character doesn’t get a big number, though the women make up for it. “Glitter and Be Gay,” now a staple of operatic recitalists, has fun with the heroine’s conflict in ruing her descent into debauchery for the advantages of lush creature comfort. But the jewels win out, and you won’t ever hear it sung better than in Howell’s rendition.

Leann Sandel-Pantaleo, playing The Old Lady with only one buttock, absolutely stops the show in each of her numbers; first, the hilarious “I Am Easily Assimilated.” Her stage presence and air for movement simply have star power. She shows it off again in a duet with Howell in “We Are Women,” and in an exuberant quartet of conniving crooks, “What’s The Use?,” all bemoaning their having to pass upward their ill-gotten gains.

The image-obsessed Maximilian (Leroy Y. Davis), one of many characters who arise from the dead, and serving maid Paquette (Rachael Braunstein) both did funny and impressive portrayals.

Many of the ensemble pieces, under Jay Lesenger’s imaginative direction, were brilliantly conceived. The “Auto-da-fé” number, with the gleeful audience enjoying the Spanish Inquisition executions as entertainment before lunch, was barbaric enough to be unsettling. Lesenger had plenty of possibilities, between venues of Westphalia, Paris, Lisbon, Spain, Montevideo and Venice, and made the most of each tableau. When “an unknown man from a tavern” gives Candide a commission on a ship, it just happened to be Osgood stepping down from the podium.

Candide’s accidental murders of Cunegonde’s two sleazy alternating lovers, the Rabbi and the Archbishop, were hilarious; you can imagine Bernstein chuckling at giving both disciplines equal carnality time.

In two places, as Cunegonde and The Old Lady live the high life with the Governor in Montevideo, or with Candide and Paquette in El Dorado, where there is no stress and only contentment, boredom sets in, triggering a need to go — somewhere. Voltaire’s telling us that we’re always looking for something which will always be slightly out of reach. The exit from El Dorado, carrying sheep and gold, came in a Wizard of Oz- like balloon getaway.

The show’s sets are simple but very effective, with details on their creation described in Georgia Davis’ separate story today. Rear projections give informative and amusing clues to the locations. In every chance possible, the large cast moves in dance and swirling motion, under Mara Newbery Greer’s direction, with a wealth of cleverly designed costumes and wigs in evidence. A suddenly appearing chorus seems contrived in opera, but, in musical comedy, it seems perfectly natural. It’s not a stretch to call this production lavish.

Considering that Bernstein’s centenary will be celebrated on the 25th of August all over the world, let’s put Candide in perspective relative to Bernstein’s remarkable career. He may have wanted to be the great symphonist, perhaps the next Mahler, but his true genius was in theater, extending its boundaries as he would later in his stunning MASS. Opera was too heavy for this project, simple numbers not enough, so this eventual hybrid stretching of the American musical comedy form was the answer — though it took many iterations to get there.

By the time Lillian Hellman suggested the work to him, the 35-year-old assistant New York Philharmonic conductor (who would become music director four years later) had already composed the ballet “Fancy Free” and its Broadway adaptation On The Town, a one-act opera Trouble In Tahiti, another hit show Wonderful Town, his first (“Jeremiah”) symphony and the second (“The Age of Anxiety”),and the score to the film “On The Waterfront.”

Hellman, Bernstein and his wife, Felicia, began work on the show, and, reflecting the aftermath of the disgraceful McCarthy red-baiting hearings, Hellman’s take on the classic was quite dark. Bernstein was also working with Stephen Sondheim on another show, originally tentatively titled East Side Story, when Candide opened and lasted for 73 performances, a seeming dud, with the smash premiere of West Side Story only months away in 1957.

John LaTouche, Dorothy Parker, Richard Wilbur and even Sondheim had hands in 1973 and 1982 versions; other operatic and concert versions and videos attempted to bring more focus, but something was always slightly missing in the story’s flow despite the brilliant score. The current version, based on a 2004 Lonny Price concert version is, as Lesenger said, “less literal to Voltaire, but swiftly captures the effervescence, irony, outrageous humor and sheer genius of Leonard Bernstein’s youthful score.” Kudos to the Chautauqua Opera’s team for choosing this version, which finally works. Don’t miss its final show at 7:30 p.m. Monday, July 30, in Norton Hall.

At the end, Candide still has his completely incomprehensible belief in universal goodness, and Cunegonde, having used her beauty as a useful commodity despite defilement by a long list of wealthy swain, may be just as innocent when it comes to genuine feelings.

The beautifully staged finale, “Make Your Garden Grow,” defines the moral of this fable — happiness can be chased, pursued, lost, stolen or bartered for, but its elusive prize of useful work and contentment is within us all the time. Thanks, M. Voltaire, for the tip, and thanks also to you, dear Lenny.

Tom Di Nardo has written on the arts for the Philadelphia Daily News since 1982. His recent books include Listening to Musicians: 40 Years of the Philadelphia Orchestra and Performers Tell Their Stories: 40 Years Inside the Arts. He has also written Wonderful World of Percussion: My Life Behind Bars, a biography of legendary Hollywood percussionist Emil Richards.