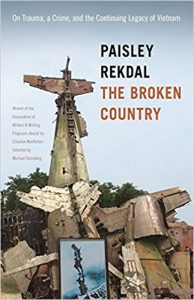

Paisley Rekdal is not a journalist by training, but she conducted dozens of interviews to complete The Broken Country: On Trauma, a Crime and the Continuing Legacy of Vietnam.

And though her work is complete, she has found that she cannot stop asking questions, listening to stories and witnessing memories unfurl. In fact, the more she interviewed, the more sensory her questions became.

“By getting people to actually relive their memories, I got better stories, and I got more complicated responses,” she said. “It was more emotionally draining, however, because people started to relive their own memories in front of me, and some of those memories were painful.”

Rekdal will discuss her writing process and work in her Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle Roundtable at 3:30 p.m. Tues., Aug. 14, in the Hall of Philosophy.

The Broken Country opens with a complicated 2012 violent incident that happened outside a convenience store in Salt Lake City, Utah. The crime serves as a jumping-off point to explore the continuing psychological and cultural effects of the Vietnam War.

According to Atom Atkinson, director of literary arts, The Broken Country is actually a book-length essay that blends memoir, biography and creative nonfiction — genres many Chautauquans will recognize from this season’s previous CLSC selections.

“This is a book that is extremely nimble, because it knows it has to be in order to communicate something (like trauma) that can often seem elusive and even invisible,” Atkinson said, “(and) is not experienced by everyone, but is certainly alive in the mainstream culture.”

Rekdal’s work also speaks to Week Eight’s overarching theme of “The Forgotten: History and Memory in the 21st Century.”

“With The Broken Country, we found a book that was also showing us the architecture of our own forgetting, and how that very architecture is the room that someone else is suffering in,” Atkinson said.

They also said Rekdal has an “incredible” ability to translate dense subject matter and scholarly work into a book that is very readable and enjoyable.

And, Atkinson said, Rekdal effortlessly moves between moments that are “concern-specific to certain demographic groups” and feelings shared by all of humanity.

“We’re all afraid of being killed,” they said. “We’ve all found ourselves trying to be cool on a date and stumbled into a strange cultural moment with someone else.”

Rekdal teaches at the University of Utah and has authored essay and poetry collections; she is also Utah’s poet laureate.

Rekdal said that poetry, much like other forms of the written word, are about representation and retelling.

“As a poet, you train yourself to see connections between stories that, on the surface, have nothing in common with each other,” she said. “I think being a poet made me a very creative researcher because it kept me open to exploring different avenues that more conventionally-minded researchers might ignore.”

As a poet, Rekdal was particularly interested in looking at trauma in terms of “how we talk about the things that change us.”

“In that sense, it became clear that trauma was not only a genetic wound, but a culturally shared memory that can grow through our own retellings and representations of the past,” she said.

One of the themes the book explores is the role of metaphor and its relationship to the legacy of Vietnam.

According to Rekdal, a metaphor is a device that can “compress complex ideas” into a word or image. Metaphors appear in people’s everyday speech, from politicians to poets.

In her book, Rekdal argues that “Vietnam” has become a metaphor.

“It’s almost impossible to say that word and have it only mean the country,” she said. “Which is, I think, something incredibly frustrating for people of a certain age from Vietnam, who feel that we continue to see the Vietnamese solely as war-torn, traumatized refugees.”

As this metaphor continues in everyday language, Rekdal said it has the power to erase narratives, people and historical facts “we choose to ignore.”

Another aspect of metaphor is that it may carry a different connotation for everyone.

“ ‘Vietnam’ can mean war, can mean American veterans’ experiences, can mean political and civil unrest at home, can mean the country itself. It all depends on the audience for whom that metaphor is being deployed,” she said. “Metaphor can unite us, but it also can reconstitute some powerful political divides.”

Rekdal knows her book speaks to Vietnam as a metaphor, but hopes it speaks “usefully” against it as well.

The Broken Country is also an exploration of the nature of trauma, which she said is both “genetically and culturally shared.” According to Rekdal, trauma informs and sculpts the collective memory of a community.

“If movies, photos, TV shows, poems and novels all carry within them traumatic legacies that we take into our own memory when confronted with them,” she said, “then to a certain extent, we become connected to the communities that we depict.”

While readers do not become a part of the community they meet through writing, Rekdal said there is space for a different type of “community connection.”

“I don’t become Vietnamese by reading and writing about the Vietnamese, but I have a stronger historical understanding of what has shaped Vietnamese-American communities,” she said, “and by doing so, have a stronger understanding of my own relationship to them.”

Rekdal did not initially set out to write an essay about trauma, although she did discover very quickly that trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder were both undeniably interwoven into the story she set out to tell.

For example, she guessed the man who committed the crime in 2012 that opens the book, Kiet Thanh Ly, was traumatized by the war and the process of picking up the pieces post-war. However, she did not realize how intensely the process of assimilation traumatized Ly and others.

“I think what I’ve learned about trauma is that though it’s slippery and weaves its way through so many family histories, it’s also a specific set of medical realities,” she said.

Rekdal worries that the word “trauma” is being widely used in modern vernacular to describe any unsettling event. She said this makes it more difficult for people to recognize and appreciate the communities and experiences of those affected with PTSD and understand why they live with trauma.

“I listened to a lot of traumatic narratives that moved me deeply, that saddened me and that I keep returning to in my own memory,” Rekdal said.

Although she carries these stories in her memory, she is not traumatized by them, she said.

“I think we need to be clear about how we remember and preserve traumatic historical memories while still standing apart from them so that we don’t make ourselves the ultimate focus of other people’s narratives,” she said.

Rekdal said the process of writing The Broken Country has opened new concerns about the nation’s dialogue surrounding trauma.

“This has much to do with the #Metoo movement, I think, as well as the horrifying number of African-Americans killed by the police and white citizens,” she said. “Even as I feel I have answered my own questions about (the) case, the questions that I examine around trauma itself still linger for me.”

Although Rekdal always knew this was an important story, she was not always sure she was the right person to tell it.

Rekdal is Asian-American, but she comes from an “incredibly different and comparatively privileged background” than some of the subjects in her book, she said.

“I am the descendant of people who fought in the Vietnam War, or who enlisted during the Vietnam War, but I myself never had to flee my own country,” she said. “I am biracial, like one of my interviewees, but I am not the product of war, even as my appearance makes my identity ‘political’ to many people.”

Rekdal realized that her identity as somewhat of an “outsider to the experiences” of those she wrote about in her book worked to her advantage.

“We have a tendency to assign subject matters to particular identities, or to assume that only people who have experienced the same thing will be interested in that experience,” she said. “When it comes to legacies of war and trauma in America, I think these attitudes subtly reinforce the idea that we can forget about traumatic events if they happen in the past and to relatively small groups of people.”

For example, as fewer people remember a war, Rekdal said society assumes the war is “finished” for the nation. This attitude neglects the realities of trauma and those it affects.

“I think the more people who want to remember the past and its continuing effects on us in the present, the better,” she said. “In that, we have to grow the community of our historical memory. My being an outsider may, in that sense, be crucial. ”