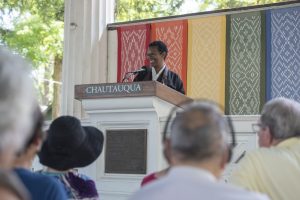

“This is at least 2.0, if not Advanced Placement,” said the Rev. angel Kyodo williams, prefacing her afternoon discussion on the intersection of race, religion, history and culture.

A multiracial, black and queer Zen Buddhist teacher, williams delivered her lecture, “Race in America: Myths, Madness, Redemption & Belonging,” at 2 p.m. Tuesday, August 20 in the Hall of Philosophy, continuing Week Nine’s Interfaith Lecture Series, “Exploring Race, Religion, and Culture.”

“We often think about race and racial justice in terms of the law and … advocacy,” williams said. “But we all know that, actually, human beings don’t shift so much around the law as we do around hearts and minds. We have never had a conversation about race in America; we’ve had a lot of talking at it, we’ve had a lot of talking about it. … A conversation is where hearts and minds get changed.”

Heralded as “the most intriguing African American Buddhist” by Library Journal and “one of our wisest voices on social evolution” by “On Being with Krista Tippett,” williams has been transforming society through transforming individuals’ inner lives for over 20 years.

“Love and justice are not two,” williams said. “Without inner change, there can be no outer change. Without collective change, no change matters.”

America, williams said, rests upon myths deeply embedded in institutions, which leave out marginalized people who — metaphorically and physically — built this nation.

“We leave these people out of our history, and so we are left with the myth of an America that is and has been founded upon meritocracy,” she said. “The myth of our country is a country that has come about as a result of meritocracy, the hard work of people — a limited number of people — most often defined and relegated to a small corner of heterosexual, white, Protestant, Anglo-Saxon males.”

With a nearly 400-year history of oppression in this country, williams said that these myths are blindly supporting ideas of opportunistic nationalism and freedom in the United States. This renders people confused and dazed by ignorance, she said, wondering: “What is wrong with people that are not able to take advantage of those opportunities?”

However, the metaphorical “race” — as williams put it — was never equal. People who are slow to cross the finish line are deemed incapable, ill-equipped and untalented; conversely, those who win the race, are dubbed talented and “endowed with great capacity,” she said.

“We have this enormous gap, not just in our sense of a race divide, but actually in our imagination of who each other are and what it is we are capable of — no one acknowledging the fact that, actually, the race began and the firing gun went off and a certain set of people were allowed to run and run, and run further,” williams said. “But before they were allowed to run and run further, they tied up the other folks. … They got to tie them up first, bind them, leave them behind the finish line and start running — 200 years, give or take.”

The result is a narrowed view of the “fruits of the meritocracy”; the success of some is to the detriment of others, she said. This is now imprinted in American culture, and “culture is not so easily unsettled,” she said.

The remnants are left in U.S. institutions like the justice system and even the U.S. Constitution, which intended to exclude women, people of color and immigrants — nearly 30% of Tuesday’s Hall of Philosophy attendees, she argued.

“(The Constitution) certainly didn’t intend for us to be in this space together,” she told the crowd. “And it certainly, certainly didn’t intend for me to be up here in front of you. We continue to reference this document and pin all our hopes and prayers, our sense of possibility and potential, on a document and the system and the myths, as if that does not … degrade us.”

Such a circular approach created a sense of madness for williams — that she continues to participate and pin her hopes and optimism in a system set out to belittle nearly 50% of the population. Such a system positions “whiteness” as the “height of human achievement,” she said — an unscientifically supported claim that has indoctrinated a population.

“It has created, for my white siblings, a reduced inability … and induced them into a kind of social madness, so that we’re not able to actually see and recognize that the brokenness in our society is — and not primarily a brokenness that affects people of color — a brokenness that affects all of us. … This is a large-scale social illness that has kept us from each other and kept us from being able to recognize and relate to each other with a … capacity for humanity that is our birthright.”

Comparing this phenomenon to taking a pill that would remove all feelings of empathy, compassion and humanity, williams said that “pill” has been passed on for generations, and such emotions are now obsolete. The pill has been so prolific, she said, that society can’t remember when it was “seduced” into the idea of whiteness.

“We no longer recognize, even though it’s written in the history books, the ways that laws were set up to induce us and participate in a system of enslaving human beings and treating them as property to be traded like currency,” she said. “We no longer, therefore, recognize that we have reduced our collective humanity to a system, to an idea, to a myth, that exists for no other reason but for profit or gain.”

But dismantling these myths is greater than tackling racism — it’s about attacking a culture rooted in celebrating whiteness, she said. Above the scholarly works, historical evidence, media, lectures and seminars, williams said the answer is an internal conversation.

“If we’ve been seduced into an idea of who we are … or who we are not, I don’t know how it would be possible to be the fullest expression of ourselves or step into the fullest expression of our humanity, if we don’t actually know who we are,” she said. “If we’re happy with the pill that has induced us into this myth, then we should just carry on. But if we’re just a little bit curious as to what it would be like to not have the myth of race obscuring our vision, our sense of possibility, our sense of promise, … then we owe it ourselves to ask these questions, be in these conversations and redeem ourselves and generations behind us.”