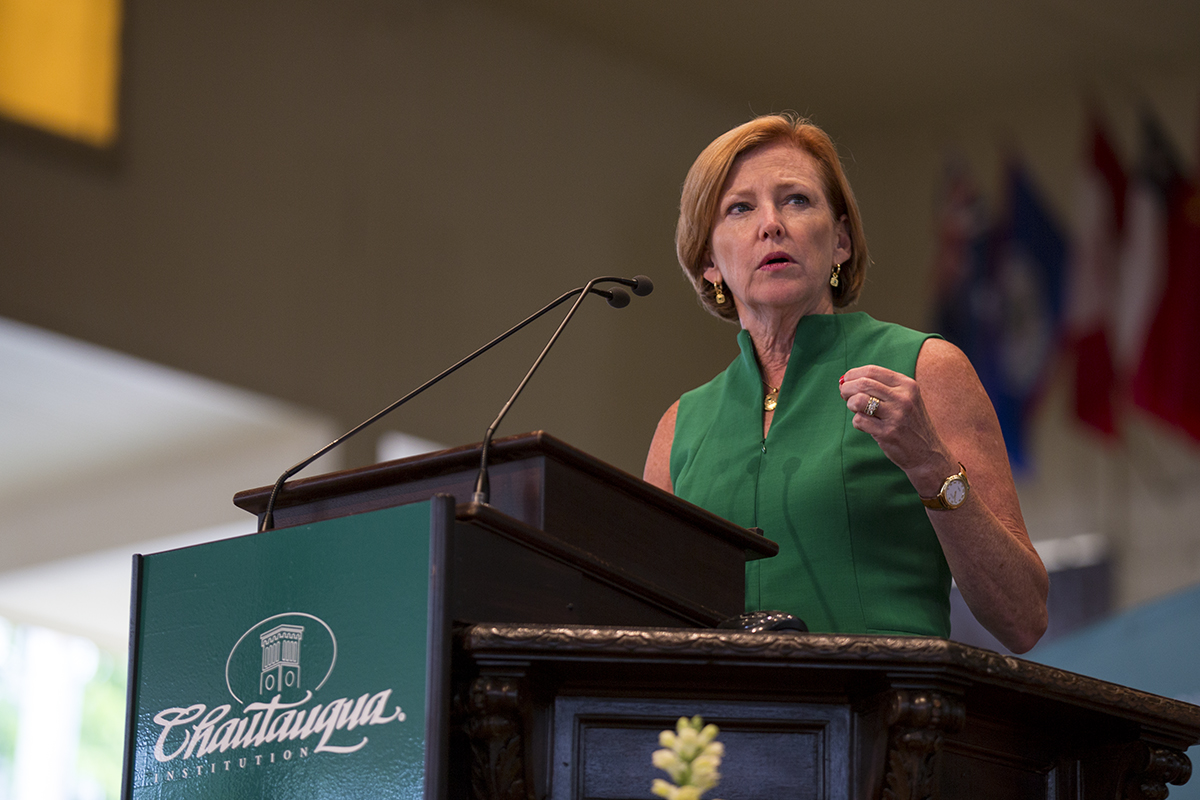

To Ellen J. Kullman, ethical and moral leadership serves as the backbone for any successful business.

Kullman, former chief executive officer at E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, continued the weeklong theme of “Moral Leadership in Action” during the Thursday morning lecture with her discussion on the core values of DuPont and how catering to the needs of all stakeholders plays a major role in moral leadership.

Moral leadership has been a part of DuPont since Éleuthère Irénée du Pont founded the company in 1802 as a gunpowder mill. In 1818, an explosion at the plant killed or injured more than a third of his staff and half the plant laid in ruins. The shock wave from the explosion could be felt 50 miles away, Kullman said.

“A less tenacious business leader might have folded his shop right then, but E. I. didn’t,” Kullman said. “He rebuilt his mills. He succeeded in getting his workers back to business. He changed some of his processes, and his business was back on track.”

Though some may believe his actions to be purely entrepreneurial, Kullman said he took a further step. He helped his workers whose houses were destroyed in the explosion. He gave the widows a pension. He paid for medical care for those injured — long before workers’ compensation became a United States law.

E. I. did not do these things out of a legal obligation. It was a moral decision he made to help the employees who were affected by the explosion.

Kullman said E. I.’s son-in-law reflected on the incident: “It is our duty to do what we can to atone for the loss.”

This tragic event led to the reconstruction of DuPont’s core values. During Kullman’s tenure as CEO, she focused on developing an ethical core value to provide employees with a “clear guidance for navigating the global landscape of modern business.”

“I view ethical leadership as a subset of moral leadership,” Kullman said. “I see ethics as table stakes. It’s the minimum a company has to do to claim any aspect of moral leadership.”

When Kullman entered business school, ethics was not a subject of study. She entered the business field with the ethics she learned growing up through personal interactions with family, professors and employers. DuPont taught her about ethics through their core values: safety and health, environmental stewardship, highest ethical behavior and respect for people.

“[Those core values] were lived out every day on the job in a corporate culture that has a moral base,” Kullman said. “We didn’t always get it right, but we worked very hard to.”

Kullman said DuPont focuses on the stakeholder theory, which leads the company to focus on four groups of individuals impacted by its production: the shareholders, employees, customers and the public.

“If we engage our employees, if we satisfy our customers, if we support the communities where we operate, we would be more successful and our shareholders would greatly benefit,” Kullman said.

Taking care of all stakeholders is an important factor to the success of DuPont, which will be celebrating 214 years of production this month. In 2014, it was the fourth-largest chemical company in the world. Kullman said many business are focusing on short-term goals rather than long-term goals.

“It takes years and years to build, but it only takes a second to lose their confidence, whether it’s your employees, the community or your customers,” Kullman said. “If you look at only one of the four, you’re not going to withstand the test of time.”

Kullman also touched on the differences between what is legal and what is moral. In a perfect world, the two would be interchangeable, but Kullman said that is not always the case.

When Kullman became CEO in 2009, many employees were being laid off. Products were being made but not sold, and Kullman wanted to find a pay to incorporate more money into the company without laying off hundreds more employees.

One legal way to do that was to cut the pay of some employees. Cutting pay without a reason was legal in both the United States and Japan.

“I didn’t think it was right,” Kullman said. “I didn’t think it was morally right and acceptable to force U.S. and Japanese citizens to take a pay cut where employees elsewhere in the world were not.”

Kullman asked her advisery board to think of another solution that would impact all employees equally in all countries.

The company decided to ask all employees to take one week off without pay and all management to take off two weeks without pay, Kullman said. The unpaid week was optional for employees because the company understood not all individuals were stable financially. However, the company stressed its appreciation for those who did take the week off.

DuPont received no complaints about the company’s offer, and 85 percent of employees took the unpaid week off.

“People were proud to have participated,” Kullman said. “Each person felt like they were helping the company survive, and it contributed greatly to morale, and I think it brought out the best in our employees.”

To Kullman, nothing is worth compromising moral leadership or the core values of DuPont. For example, Kullman said, DuPont wanted to establish a plant in India, but the companies DuPont needed to get the new plant underway were asking for a large “facilitating payment.” Kullman described facilitating payments as a legal form of bribery in the 1990s.

After speaking with some of the other leaders within the company, Kullman decided the plant in India was not worth taking the bribe.

“There were just lines we knew that we would just never cross, but if ethical leadership is mainly about black and white, moral leadership is all about shades of gray,” Kullman said. “It’s the job of the business leader to let values inform and shape the company’s culture. Values drive culture. Culture sustains values.”