When soldiers return back to their lives after serving overseas, they do not receive a handbook or set of guidelines to follow that teaches them how to go back to civilian life.

No one told Army combat veteran Wes Moore he would have a problem with lights. At night in Afghanistan, his unit used green and red lights because using a white light was like setting up a target for the enemy.

Moore was shocked when he went from an intense light discipline in Afghanistan to the vibrant nightlife of Times Square. Moore was stationed on the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Using a white light, even inside a building, would result in the sound of bombs whistling throughout the night.

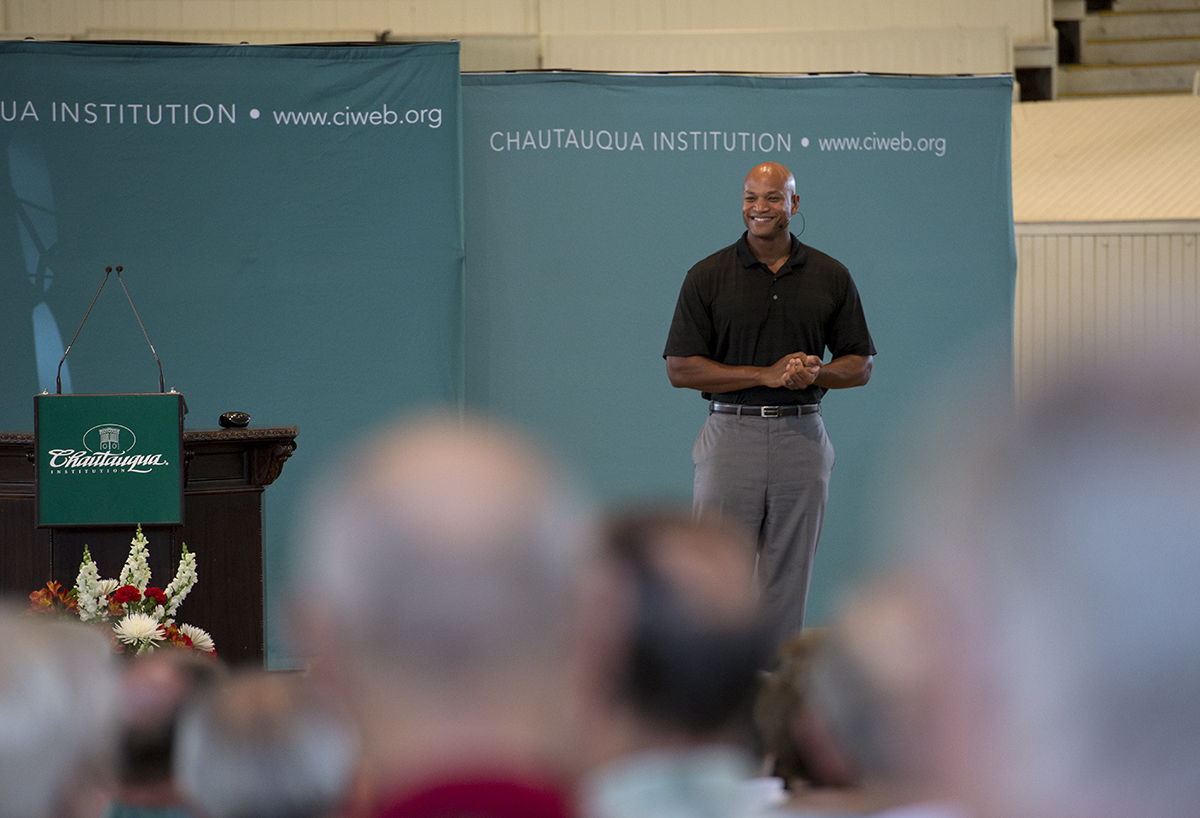

Moore spoke about the reintegration process for veterans as they settle back into their former lives during the 10:45 a.m. Wednesday morning lecture in the Amphitheater.

“There will always be a new normal that you have to transition back to,” said Moore, an advocate for youth and veterans and executive producer and host of PBS’s “Coming Back with Wes Moore.” “These were things that I wasn’t exactly sure how to prepare for. It didn’t mean that I was coming back damaged. It meant that I was coming back different. There will always be a way you have to adapt when you come back home.”

When he was 13 years old, Moore’s mother sent him to military school. He ran away from the military school five times in the first four days. However, the more time he spent at the school, the more he began to embrace the foundation military culture is build on.

He began to love the idea that the only way he would make it through school is if his friends pushed him and supported him. He lived by the words of the soldier’s creed.

“I will always place mission first,” Moore said. “I will never accept defeat. I will never leave behind a fallen comrade. This became part of our DNA that we took very seriously.”

In 2001, Moore knew his job had changed after the terrorist attacks. His unit was deploying to the war, but Moore was traveling to England on scholarship to study at Oxford. When he graduated in 2005, he went to Afghanistan with the 1st Brigade of the 82nd Airborne Division.

Many people told Moore to “thank God it was Afghanistan” when he mentioned where he would be deployed. At the time, 19,000 U.S. soldiers were based in Afghanistan, and 150,000 were in Iraq. Moore found himself at Bagram Air Base near one of the main strongholds of the Taliban.

After returning from the war, Moore started working on a project with PBS. He was inspired to share the stories of other veterans after he got a phone call one night from a former Army friend. The phone call was to inform Moore one of his old friends had killed himself. His friend spent three tours in Iraq and one in Afghanistan. He was Moore’s third friend within 18 months to commit suicide.

PBS originally wanted Moore to talk about veteran suicide. He said between 20 and 22 veterans a day were taking their own life. Although he recognized the importance of those stories to tell, Moore told PBS it’s not the only veteran story people need to be aware of.

“I don’t want the narrative to become how every single person that comes back from overseas is just completely and irreparably damaged without understanding you also have the Phil Klays and the Kayla Williamses … and all of these other people, who every day are coming back and making our society better,” Moore said.

Through the PBS special, titled “Coming Back with Wes Moore,” he wanted to celebrate veterans and tell the powerful stories of those who fought overseas. He wanted to push for social action and urgency because, though data and statistics can provide a new outlook on how jarring war can be, Moore believes humanizing those issues can have a greater impact.

“Statistics can make something seem so bad that the common takeaway is there’s nothing we can do about it,” Moore said. “I am a big and firm believer that while statistics can add context, stories promote action.”

Moore began getting involved with other veterans issues, such as lifting the ban on women in combat and “don’t ask, don’t tell,” which was the official policy on military service by gays, lesbians and bisexuals.

Moore told the story of Tammy Duckworth, an Army Reserve veteran and helicopter pilot. Duckworth was flying a helicopter when it began getting hit by indirect fire. Duckworth was unable to navigate the helicopter because the attack damaged her legs. When she awoke, the doctors had amputated both legs to save her life.

Today, Duckworth serves as the first Asian-American and woman with a disability to be elected into the House of Representatives.

“Someone explain to Tammy Duckworth that women haven’t seen combat,” Moore said. “I believe deeply, and I saw firsthand, that anyone who thinks women have not seen combat over the past 10 years has not spent time in a forward operating base.”

Though the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy did not affect Moore firsthand, he supported the lift of the policy because it affected a close friend of his. Captain Ty Hill and Moore became friends when Moore first entered the military academy at age 13. Hill became a big brother, a friend and a mentor to Moore.

Hill served between three and four years in the Army before leaving. Moore assumed Hill’s obligation to the military was up, but he later learned the truth that Hill was sent home after being honest about his sexuality.

“He left the military was because he had the audacity of telling the commanding officer his truth,” Moore said. “The fact that he said, ‘If we’re going to be a part of an organization that prides itself on honor and integrity, I can’t sit here and lie to you and everybody else every day.’ ”

Within six weeks, Hill was out-processed and left the military. That outraged Moore because he had heard of cases where it took eight months to a year to out-process someone who was involved in violent crimes against spouses, yet Hill was forced to leave so quickly.

“I got involved in this issue simply because I felt if someone could make an argument to me that somehow this was making our country less safe, then I’m listening,” Moore said. “He was the kind of officer that I would trust my children to serve under him.”

Moore also discussed the phrase “thank you for your service.” Although the phrase is meant to show appreciation and gratitude, Moore said the conversations stop there far too often. People worry about asking the wrong questions or triggering a bad memory, so the common occurrence is to say “thank you” and move on.

“Often times the fear of asking the wrong question means you ask none,” Moore said. “The mental interpretation of the veteran when nothing is asked — the interpretation is you don’t care.”

He listed questions: What was the food like? What was the temperature like? Tell me about your interactions with the Afghan people.

Moore argued asking questions is essential because otherwise, individuals do not truly know what they are thanking veterans for.

“ ‘Thank you for your service’ means it’s the beginning of a conversation,” Moore said. “It’s better understanding what it is that this person did and saw and how can we help when it comes to their integration process and understanding the humanity that underlines all of this stuff.”