This is the second in a series of occasional columns that examines some of this year’s CLSC selections and how they fit into the broader conversation about contemporary literature.

After making my way through a mini-review of Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street on Monday, I got to lead a short discussion on the book with some fellow Chautauquans.

What stayed with me after was a response to a question I tacked on at the end. I asked the audience if Cisneros’ choice to tell the story in vignettes was a satisfying experience for them.

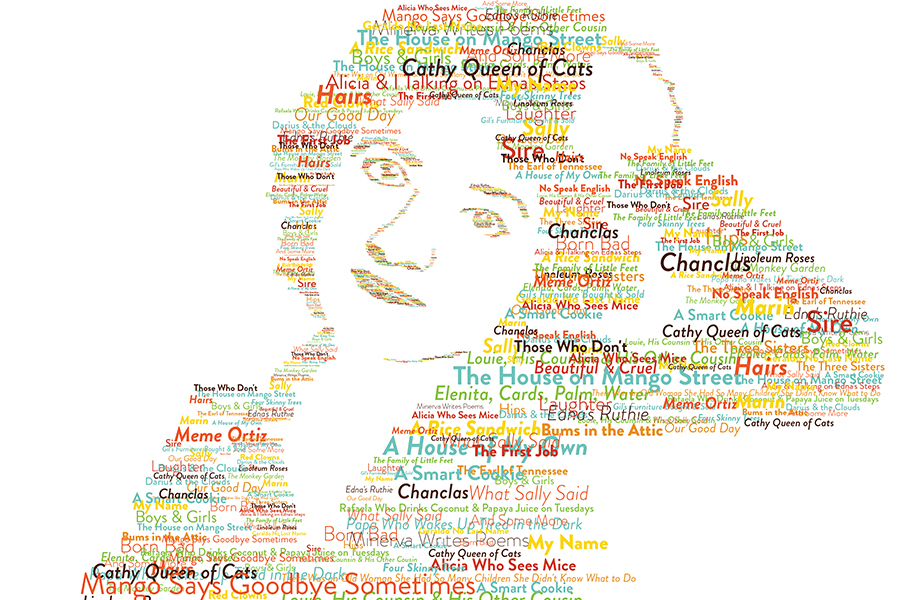

The answer that struck me the most came from a woman who said that she was excited to read the book, but when she first picked it up and started flipping through it, she balked a little at its diminutive chapters. Cisneros relays the story of The House on Mango Street in 44 vignettes, most of which range from two to five pages. The woman said she came around by the end of the book, though — Cisneros had convinced her that this was the full portrait of her character Esperanza Cordero.

I, too, struggled with the idea that I could become invested in a character whose life is portrayed in such brief flashes and in such a small space: a little over 100 pages.

I was wrong, of course. Cisneros knows what she’s doing, and the power of the book comes from the brevity of these “little stories,” as she refers to them in the introduction.

As I read these little stories, I kept thinking of a line of Zadie Smith’s from her essay “Middlemarch and Everybody” that’s stayed with me since reading it. In the essay, she extolls the virtues of George Eliot’s eight-volume masterpiece and makes clear why the novel’s excessive length is integral to its achievement. But she also makes a crucial point about literary form.

“What is universal and timeless in literature is need — we continue to need novelists who seem to know and feel, and who move between these two modes of operation with wondrous fluidity,” Smith writes. “What is not universal or timeless, though, is form. Forms, styles, structures — whatever word you prefer — should change like skirt lengths.”

It’s an idea I love, mostly because I think Smith is a genius. But what she hits on is essential, and I think that’s why I remember the skirt-length simile: We’re always going to need novels, but who’s to say what form they should take?

Cisneros has been asked about form before, particularly as it concerns The House on Mango Street. In a 2002 interview for The Missouri Review, Gayle Elliot asked Cisneros for her definition of a short story. Cisneros responded:

“I don’t know what the definition of a short story is, and I don’t even care to answer that question. That’s something somebody in academia would think about. I just want to tell a story, and if people listen, and if it stays with you, it’s a story. For me, a story’s a story if people want to hear it.”

It’s a wonderful answer, lovely in its bluntness. And it’s in line with how Cisneros seems to view her work. She writes in the introduction to The House on Mango Street that when she was writing it, she didn’t want to create a book “that a reader won’t understand and would feel ashamed for not understanding.”

It’s a refreshingly earnest view of literature. Some authors purposely write in an opaque way. They want their work to befuddle, confuse and puzzle the reader. That’s all well and good, I guess, and I know there are writers like this that I admire.

And it’s how works tend to become part of the canon: when there are no easy answers (or answers at all), we continue to read, write and discuss. That’s stimulating work. But Cisneros’ view of her writing — that she just wants people to understand it and see themselves in it — is invigorating.

When I got the chance to interview Cisneros last week, I started by telling her that I was excited for her visit. I was taken aback by her response. She said thank you, because she’s polite, but then she asked me why I was excited for her visit.

My instinctive answer, which I kept to myself, was that she’s Sandra Cisneros. She’s a poet, a novelist, a short story writer and a memoirist whose work is widely anthologized and respected. She’s a key figure in Chicana literature, and she helped establish the Macondo Writers Workshop, which is meant to support up-and-coming, socially conscious authors.

How could I not be excited?

In the 34 years since its publication, The House on Mango Street has become a regular part of the curriculum in many high schools, including mine. I asked Cisneros what she thought about the novel’s staying power.

She surprised me again, asking me where I went to high school. I told her I was from Elizabethtown, Kentucky.

“That’s even more exciting,” she said. “Elizabethtown, Kentucky, is probably the farthest reach away from where the stories came from. If people in Elizabethtown can see themselves in these characters, then the story will have done its work.”

The unfortunate thing for me is that I missed out on reading Cisneros’ work in high school by just a few years. That meant when I read it for the first time, I came to it as a 24-year-old.

I can’t imagine what I would have made of The House on Mango Street if I had read it when I was 15. I might have scoffed, might have rolled my eyes. I might have thought that there was nothing in it for me — how could I see myself reflected in the story of a teenage Latina girl growing up in Chicago? (Do keep in mind that 15-year-old boys are objectively terrible, and I was not exempt from that group.)

There’s also the opposite side: that I would have found too much of myself in it and rejected it, simply because it was hitting a nerve.

While I’ll never know what 15-year-old Ryan would think of The House on Mango Street — and I don’t think I want to — reading it as an adult was thrilling. I found bits and pieces of myself in nearly all of these “little stories” that Cisneros gives us. She does what Smith discusses in “Middlemarch and Everybody”: the novelist’s work of switching between knowing and feeling, allowing her form to suit her content and letting the reader find what they need.

It’s an impressionistic approach, but it also feels keenly attuned to the experience of being a teenager. And it definitely strikes the nerve that probably would have been too raw for me when I was 15. Nobody remembers the litany of everyday events that simply get us from day to day when we’re that age, but we do remember certain moments. And in The House on Mango Street, Cisneros gives us those moments in brief, beautiful flashes that capture the little things we tend to carry with us forever: a kiss, the simple joy of friendship, the realization that you’ve hurt someone deeply, a moment of self-actualization.

Anyone could find themselves in this book.

When it comes to finding, I tend to think that we come across the right books at the right times in our lives. I hate how earthy-crunchy and hippie-dippie it sounds, but whatever. I really do believe it. There’s nothing more exciting than knowing that you’re reading something precisely when you should be — something that can stir you up and illuminate parts of yourself you didn’t even know about.

I’m not alone. Cisneros believes in this hippie-dippie stuff, too. In that same interview with The Missouri Review, she says, “We may say, ‘Oh, that story didn’t do anything for me,’ instead of saying, ‘I’m not ready for that story.’ We blame the author or the story itself; but I really think that you have to hear a good story at the right time in your life.”

She’s not wrong.