The legal system often forgets that the line between right and wrong is blurred. But 11-year-old Perry T. Cook hasn’t.

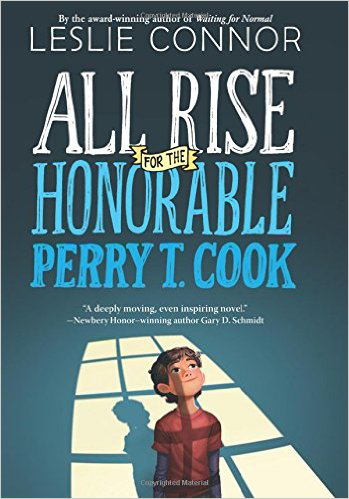

In Leslie Connor’s All Rise for the Honorable Perry T. Cook, Perry is forced to leave his mother and the home they’ve made at the Blue River Co-ed Correctional Facility when the district attorney, Thomas VanLeer, finds out a convict has been raising her son while serving her sentence. The book, Week Five’s CLSC Young Readers selection, will be discussed at 4:15 p.m. Wednesday in the Smith Memorial Library, followed by a program about constitutional rights.

“I was excited to find a book that dealt with (the theme ‘The Supreme Court: At a Tipping Point?’),” said Karen Schiavone, Special Studies and youth programs associate. “Most books that have anything to do with the legal realm for kids are biographies. … I wanted to find something fiction if possible because I thought it would be more fun.”

Connor’s novel gives a kid-friendly approach to discussing mature issues that will be explored this week through lectures around the Institution. During Wednesday’s program, Schiavone will use resources from the National Constitution Center to teach children about the Supreme Court and the role of law in today’s society.

Though his upbring is unorthodox, Perry didn’t mind growing up in the prison. In fact, he describes it as home and loves the extended family of inmates and prison workers who helped raise him. As part of a school project, Perry begins to document the stories of the inmates and discovers that many of them are not the one-dimensional criminals society paints them to be.

As Perry’s best friend, Zoey, said, “Once you know the person, well, it makes you care.”

While Perry and the inmates of Blue River are fictional, Schiavone said, the stories they represent are all too real. Schiavone, who graduated from law school and passed the bar exam before deciding law was not the field for her, said Connor’s story is well researched and accurate. The stories of Blue River prisoners persuaded to confess or denied counsel echo those of real-life prisoners whom Schiavone said the system takes advantage of.

“This happens all the time,” Schiavone said. “Our system functions on innocent until proven guilty, and that is not always the case.”

Although Schiavone didn’t find law appealing, she said she was passionate about “being a voice to those who don’t have a voice legally.” In going along with Week Five’s theme, she wants children to understand that under the Constitution, they have rights, too. One part of the novel that struck her was when VanLeer says he will not discuss legal matters with Perry, and the adults are taking care of it.

The roles of good and evil are switched in Connor’s story. VanLeer, who theoretically is working for the people, is the antagonist. The reader’s heart goes out to the inmates who are convicted of violent crimes, even manslaughter.

“It’s easy to lose hope or faith in adults when they say ‘they’re taking care of it,’ ” Schiavone said. “But there are people who will help you and that you can turn to and trust. Sometimes it takes a little effort to find those people but they’re there.”

It is the VanLeers of the world, those with skewed moral judgments, who cause problems for the real children, who Perry represents. In an author’s note at the end of the story, Connor wrote that one in 28 school-aged children in the United States has a parent in prison. Schiavone said it is important to have books that show the perspective of these children.

“I haven’t seen any books that offer a ‘happily ever after’ ending when one of the main characters parents is in prison,” Schiavone said. “And maybe that’s unbelievable, but I like to believe that everyone will get their happily ever after someday.”