What do Willie Nelson, Doris Kearns Goodwin and Little Richard have in common?

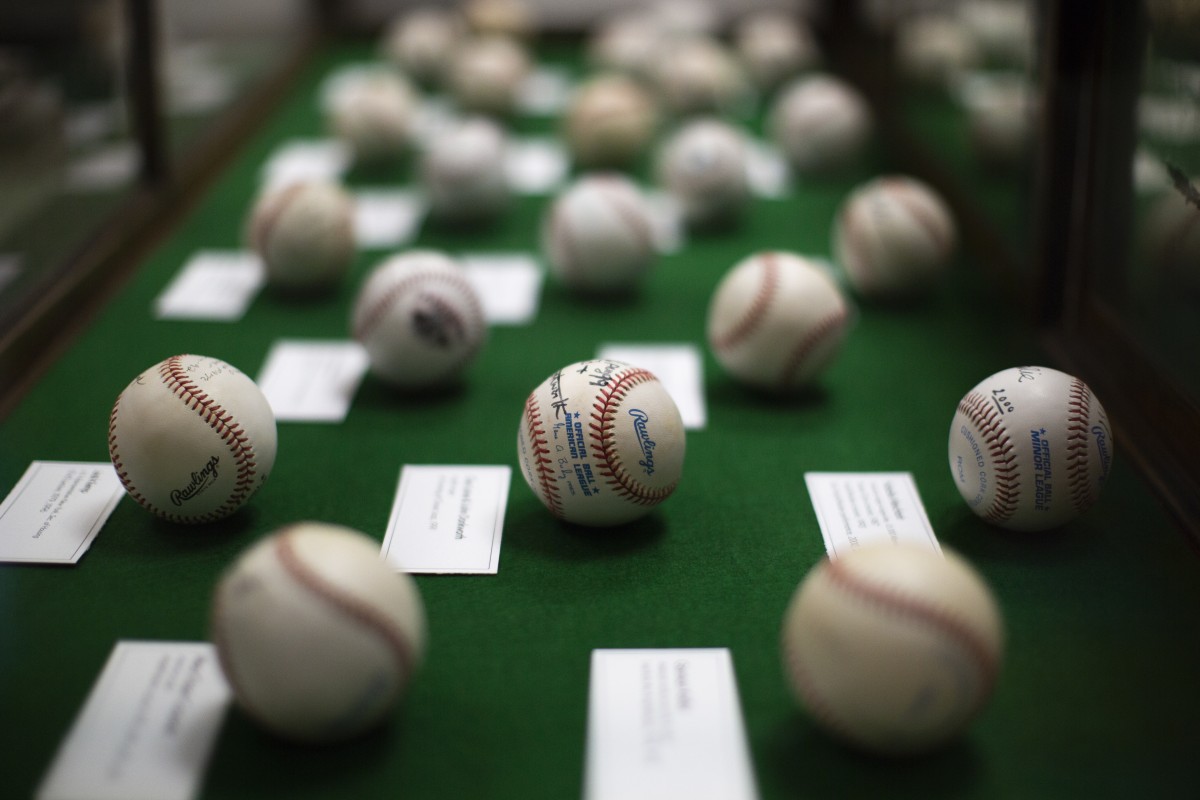

Sure, they have all appeared at Chautauqua, but more than that, they have all signed baseballs commemorating their visits. So have Natalie Merchant, the Smothers Brothers, Tom Ridge, The Four Tops and 15 other big-name performers and speakers.

Chautauquans can see them all in a new exhibit called “Take Me Out to Chautauqua,” at the Oliver Archives Center on South and Massey. The building is open to the public from 10:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. Monday through Friday during the season, and by appointment during the off-season.

Chautauqua Institution does not have an official museum, but the Archives, in addition to being the repository for 144 years of papers and other records, houses all sorts of historic artifacts. Recently, a number of these items have been re-organized into user-friendly displays at the Archives and at Smith Memorial Library.

The baseballs were collected by longtime Chautauquan Greg Peterson, a founder of the Robert H. Jackson Center in Jamestown and a lawyer known widely for his civic activism and passion for the national pastime.

According to Jon Schmitz, the Institution’s archivist and historian, Peterson amassed the collection over decades and lent it to the Archives last year. Emalee Krulish, an assistant archivist, created the presentation and several other new exhibits in the main reading room of the Archives and on the second floor of the Smith.

“To Set a Watchman” is another one. It organizes a collection of patrol boxes and time clocks that were used by night watchmen from the late 19th century until the 1970s. The boxes were posted on buildings and trees around the grounds, and some can still be seen today, like the one on the Octagon Building next to the Literary Arts Center at Alumni Hall. On the lookout for fires, the watchmen would record the time of their check-in by opening the boxes with a key connecting them to a clock that recorded the time and location on a roll of paper inside.

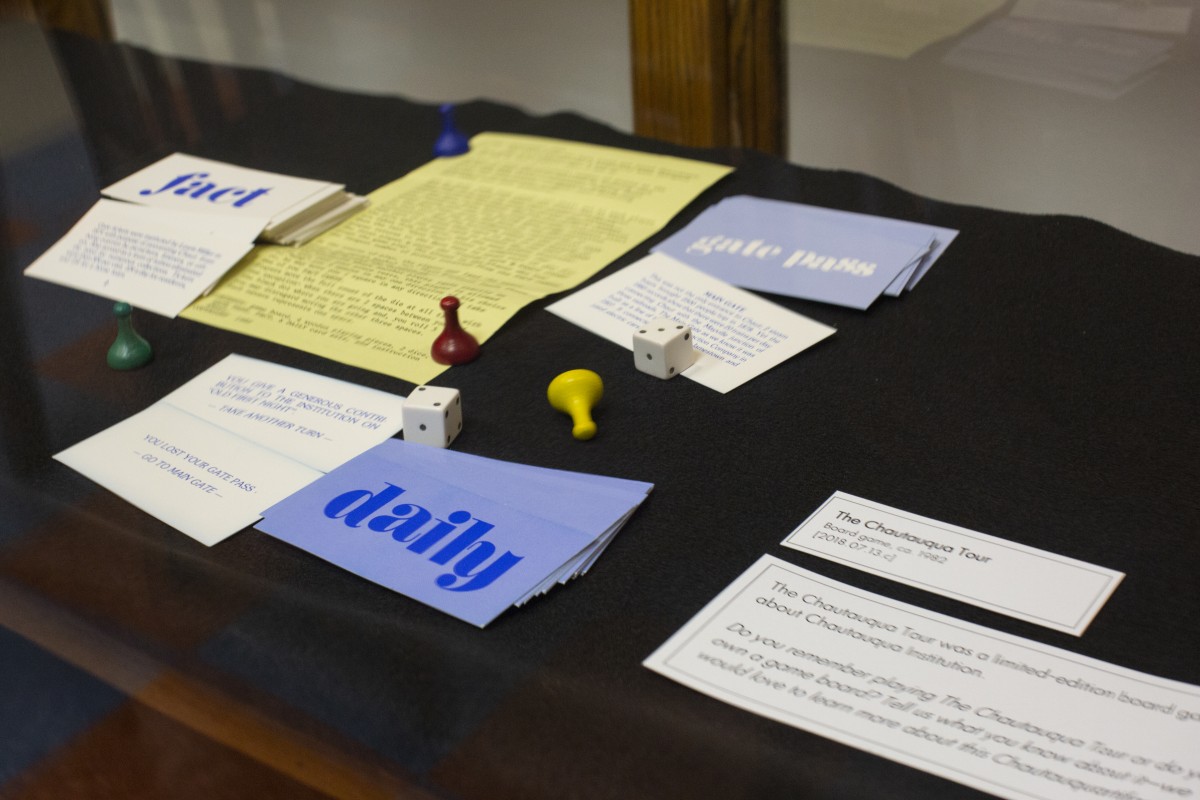

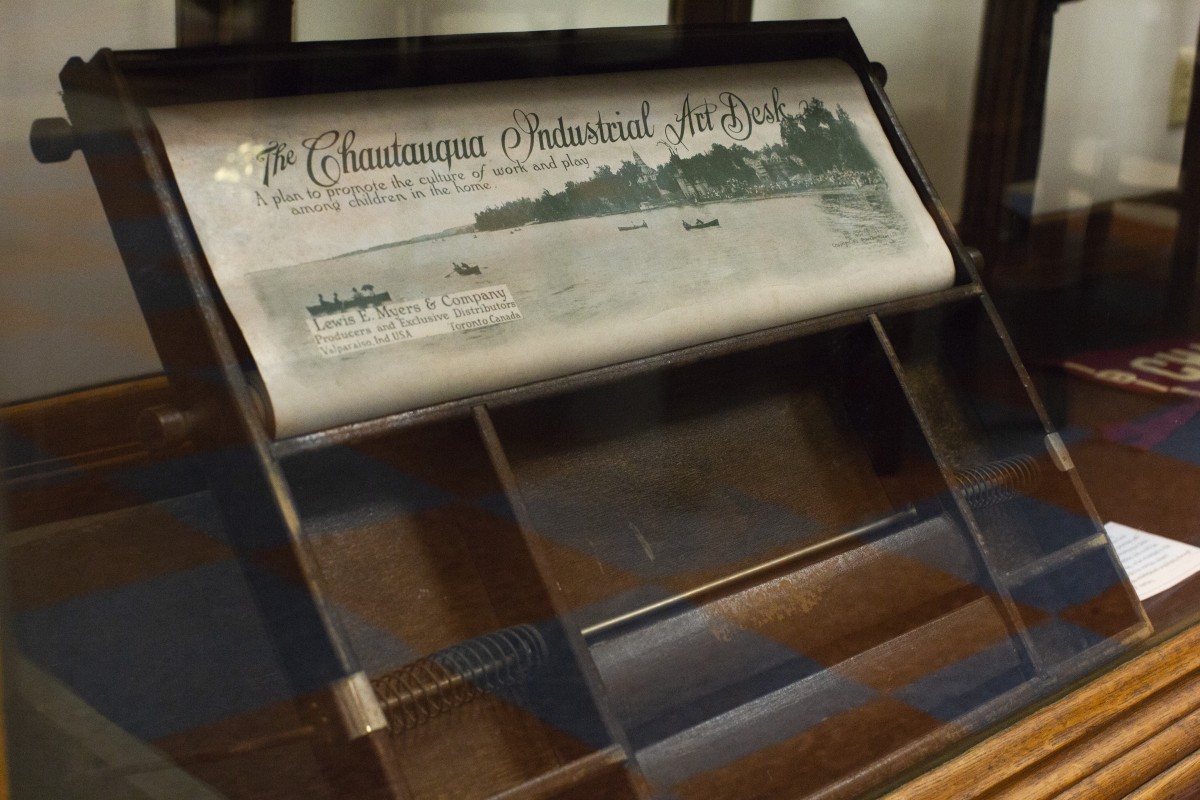

Another exhibit Krulish put together tells the story of Chautauqua through artifacts, including a board game from the 1980s that challenges players with questions like “You Lost Your Gate Pass — Go to Main Gate.” Also featured are a gigantic gavel; wooden carvings of Lewis Miller and John Heyl Vincent, the founders of Chautauqua, a Communion tray; and a children’s portable art desk from 1913.

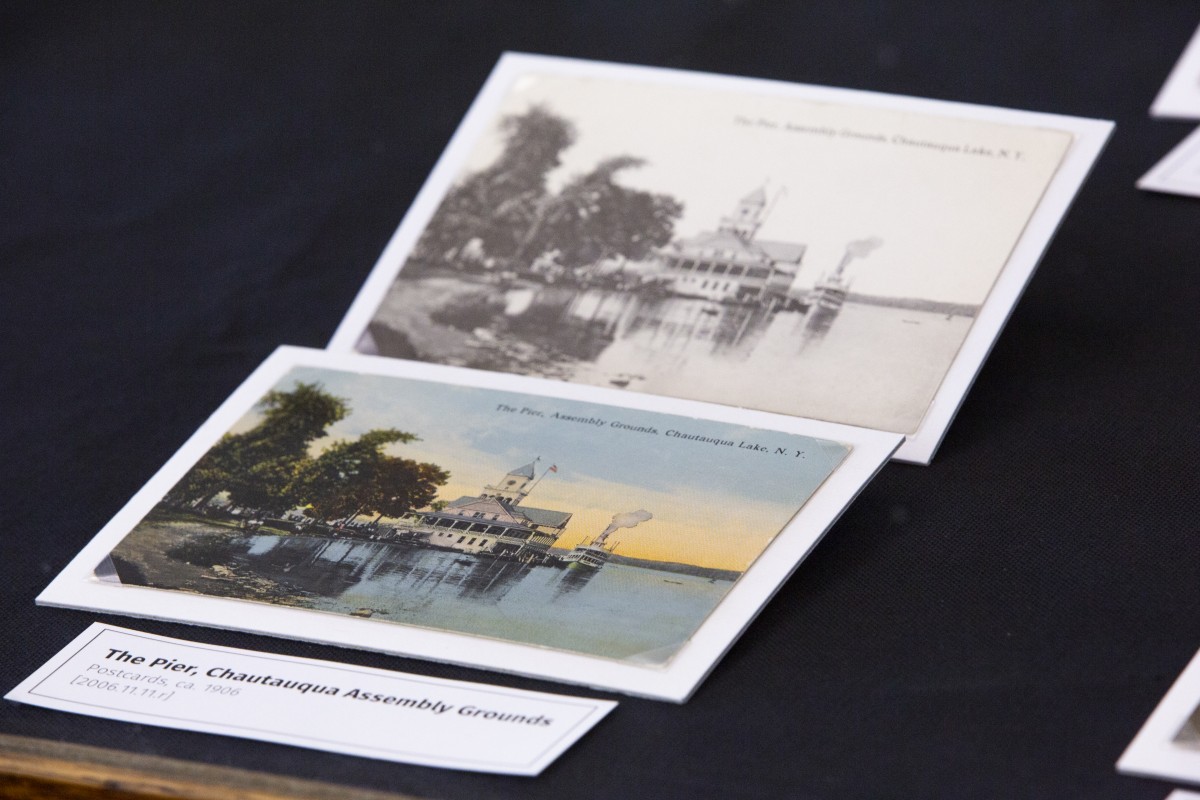

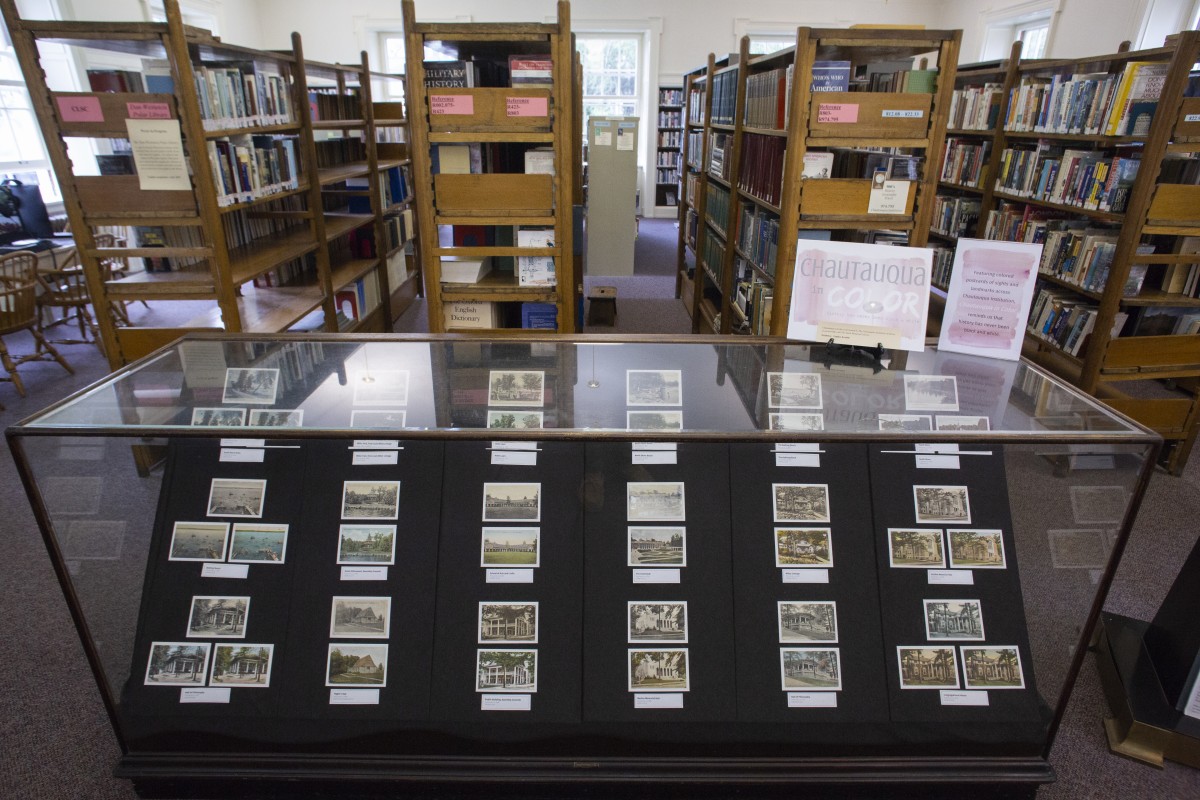

At the Smith, “Chautauqua in Color” exhibits dozens of old black-and-white postcards of Institution landmarks like the Athenaeum Hotel and Hall of Philosophy that have been painstakingly colorized. This display includes coloring book pages and crayons for children. Children can also go online to ColorOurCollections.org to color more images of Chautauqua and other institutions around the world.

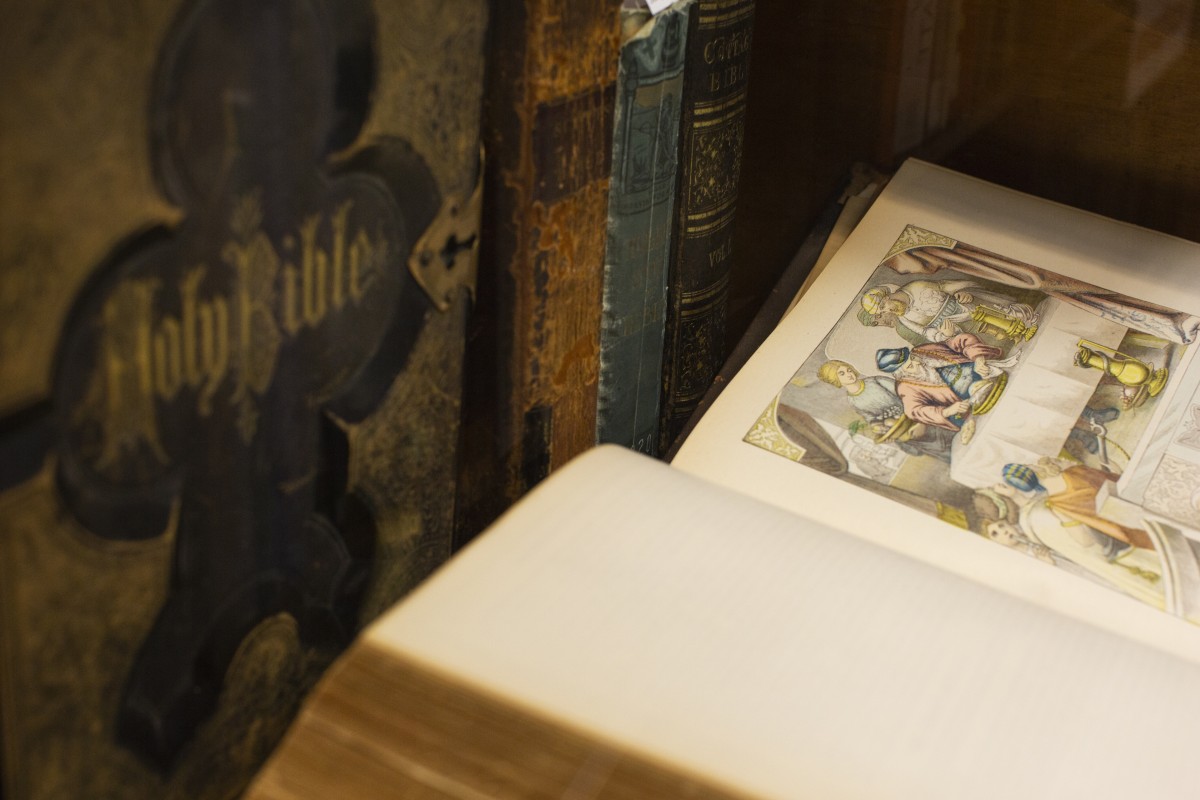

These are just some of the artifacts the Archives has on display. One collection features Bibles owned by well-known Chautauquans and unusual texts like an early Frank Beard pictograph Bible.

Also in the the Archives’ reading room is the Seth Thomas clockwork that kept time and triggered the bells at the Old Pier Building and later the Miller Bell Tower from 1886 until 1967. Its weights and cables could reach down two stories. And it still works. Behind it, on a wall, is the enormous clock face.

So, no. Chautauqua does not have an official museum, but it has the Archives, which curates the Institution’s artifacts with the same care and diligence that it brings to its unrivaled collection of documents.