One of the delights in working with the Homeboys and Homegirls is savoring their use of the English language. Fr. Greg Boyle, S.J. was sitting in his office one day with Louie, when a volunteer, Jim, asked if he could interrupt. Louie jumped up and hugged Jim.

“I love this guy,” Jim said.

“This is a beautiful man,” Louie said. “In fact, G, if we were living in Greek times …” Boyle paused as the congregation laughed in anticipation of where the story might go. “… Michelangelo would have made a sculpture of his ass.”

“Michelangelo. Greek times. Close enough,” Boyle said.

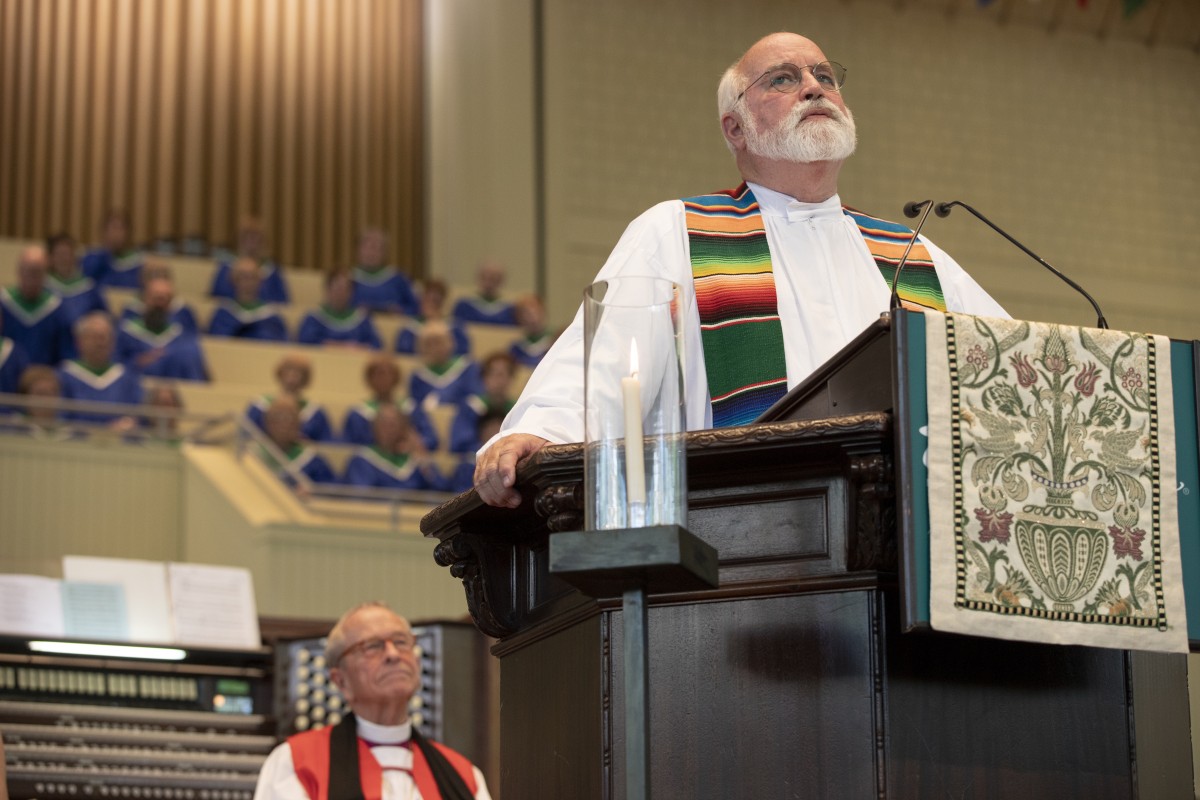

He was preaching at the 9:15 a.m. Thursday morning worship service on July 19 in the Amphitheater. His sermon title was “Breathing Air of a Richer Kind,” and his Scripture text was Isaiah 58:6-11, on true worship.

“How do we heal from shame?” Boyle asked. “I am not the great healer. The truth be told, we are all a cry for help.”

In her poem “Where Does the Temple Begin,” Mary Oliver said: “There are things you can’t reach. But you can reach out to them, and all day long.”

It is the relationship that heals, Boyle said, not the message. He reflected on the Homies’ disorganized attachments as children.

“You can’t calm yourself if you have never been soothed,” he said. “ A Homeboy told me once that watching his daughter, he saw her ‘breathing air of a richer kind.’”

Bandit was a Homie who had a tortuous family life and resisted help. Finally, he came to Boyle and told him, “I am tired of being tired.”

Bandit entered the 18-month recovery program, and for the first time in his life, he tried “trying.”

“In that community of tenderness, he was able to forgive his mother for being mentally ill, and he could finally touch his pain without judgement,” Boyle said. “He was able to transform his pain so he did not have to transmit it (to others).”

It takes 18 months to equip the Homeboys and Homegirls with the resilience to go forth into the world, so they won’t topple from what the world throws at them, he said.

Bandit got a job in a warehouse and soon ran the place, got married and had three kids.

“I had not heard from him in a while, which is good news with Homies,” Boyle said, “but he called and said I had to bless his daughter. I thought she was sick, but he said she was going to Humboldt University and she was small, and he and his wife were worried about her.”

Boyle told him he had an exorcism at 1 p.m. (“Just to see if you are listening,” he added, referring to Wednesday’s sermon), but he asked them to come at 12:30 p.m.

The whole family came and with Boyle, they surrounded Jessica, the daughter, and laid hands on her.

“I said a long-ass prayer,” Boyle said. “I noticed we were all crying, and I wondered why.”

Bandit and his family did not know anyone who had gone to college before. When Boyle asked Jessica what she was going to study, she said immediately, “Forensic psychology.”

“She wants to study the criminal mind,” Boyle said, “and I am her first subject.”

Boyle told Bandit, “I give you credit for the man you have chosen to become, and I am proud of you.”

“Know what?,” Bandit said. “I am proud of myself. All my life, I have been called a low-life and a good-for-nothing. I guess I showed them.”

And the soul felt its worth and light broke forth, Boyle said.

At Homeboy Industries, he said, love is the answer, community is the context, tenderness is the methodology.

“We must be tender to join to each other; that is God’s dream for us,” Boyle said. “Jesus is God becoming one of us. Jesus entered into relationship (with people) and created sanctuary.”

A woman came to Boyle one time and told him she had to volunteer at Homeboy because “she had a message they needed to hear.”

“I told her the minute you lose that message to come back,” he said. “Jesus did not come to work with the poor, he shared life with them. Homeboy helps them discover what makes life worth living. There is a healing capacity in relationship. We are wired to connect; that’s how our light breaks forth.”

One day Boyle received a call from Oracio, who had been in prison for five years. He was trying to stay away from the barrio and had found out that his girlfriend had left him.

“She took his clothes out of the closets and put them in a pile and burned them,” Boyle said.

“She might have been mad at me,” Oracio said.

“What was your first clue?” Boyle said.

Oracio told Boyle he wanted to “cut to the cheese,” that he needed new clothes and a ride to the store. Boyle took him shopping to get what he needed.

Having been in prison for five years, Oracio was what the Homeboys call “swole” from lifting weights. He was a big guy and “not someone you would want to meet in a dark alley, or a lighted one for that matter,” Boyle said.

As they were waiting in line to pay for the clothes, Oracio thought he saw someone he knew.

“He has a loud-ass voice,” Boyle said, “and said to the their son, and she said, “We don’t know you.”

“My bad. I thought you were someone else,” Oracio said.

“Damn, G, do I look that scary?”

“Yeah, you do,” Boyle said. “And everyone in the line, including Oracio, laughed.”

At 3 a.m., Oracio called and asked if he had woken Boyle. “I gave my standard answer, ‘No, I was hoping you’d call,’” Boyle said. “I was also hoping he would cut to the cheese.”

“All my life I saw you as my father,” Oracio said. “Have I been your son?”

“Of course,” Boyle told him.

Oracio continued: “Good, I thought so. So you will be my father and I will be your son, and nothing can separate us.”

“He discovered he was a son worth having,” Boyle said. “He found his innate goodness.”

There was a three-month period of sadness at Homeboy Industries when two Homeboys on the graffiti removal crew were gunned down.

Boyle, who is usually calm, came back from the hospital after the second death and was “trying to reset the compass of my heart.” He thought he was alone, but Chino came out of a back office and sat with him.

“Are you OK?” Chino asked Boyle. “I know this is heartbreaking, and I wish I had a magic wand to pass over the pain.”

They sat and cried together, unleashing the pain. Boyle said that the Lakota people believe that grief is holy, and “so we sat in the holiness of our weeping.”

“Everyone here is drowning in a big fast river and you ‘swoop’ us up,” Chino told Boyle. “I swear to you, if someone offered me a million dollars or the chance to swoop you up, I would swoop you up.”

“You just did,” Boyle said.

Boyle told the congregation that we all want to breathe air of a richer kind; we want relational wholeness, to share our lives and connect.

“Then the light breaks forth like the dawn and healing quickly appears,” Boyle said. “‘There are things you can’t reach. But you can reach out to them, and all day long.’ ”

Deacon Ed McCarthy presided. Alison Marthinsen, a sixth-generation Chautauquan and a volunteer with the homeless in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, read the Scriptures. The musical prelude, performed by Joseph Musser, piano, Hois, flute, and Scarnati, oboe, was “Trio for Flute, Oboe and Piano” by Joseph Musser. Musser wrote the piece in 2018 and he dedicated it to his Motet Consort colleagues, Barbara Kemper Hois and Rebecca Kemper Scarnati. The Motet Choir sang “And the Word Became Flesh” by Walter L. Pelz. Scarnati provided oboe accompaniment. Jared Jacobsen, organist and coordinator of worship and sacred music, directed the Motet Choir. The Alison and Craig Marthinsen Endowment for the Department of Religion provides support for this week’s services.