When John Keene first picked up a copy of Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred at Boston’s Avenue Victor Hugo Books, he was in his early 20s and a young member of the Dark Room Collective, an influential community of African American poets. He read the novel in a little under a week.

Benefitting from “the perspective of maturity,” Keene reread Butler’s sci-fi classic in advance of his Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle Author Presentation. The writer, professor and 2018 MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellow will give the second CLSC lecture of Week One on Butler’s Kindred, at 3:30 p.m. today, June 27, in the Hall of Philosophy.

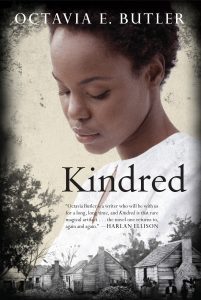

First published in 1979, Kindred follows Dana, a black woman writer, as she is transported across time and space from 20th century California to a Maryland plantation in the antebellum South. It is to there, over the course of multiple visits, that she travels back in time to rescue Rufus, the plantation’s heir and her not-so-distant ancestor. Keene characterized the novel as a Freudian-esque exploration of the “return of the repressed.”

“Dana is traveling back in time and also clarifying her present,” Keene said. “It’s the story of an individual, but we should extrapolate that to a larger system.”

Usually, CLSC books are from the past two or three years — not from the past 40. Yet there is precedent for this selection of Kindred. Atom Atkinson, director of literary arts, inherited the practice of “historic selections” from Sherra Babcock, former vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education. Atkinson felt the text provided “a really rich opportunity” during Week One, “Moments That Changed the World.”

“Octavia Butler is capable of … re-orienting how we even approach the question of what was significant in the past, or what the past is,” they said.

Tasked with inviting another author to present the late Butler’s work, Atkinson and the literary arts team immediately thought of Keene, whose short story collection Counternarratives subverts the intertwined histories of race and enslavement. Keene is also the author of the experimental novel Annotations, a poetic, partly autobiographical work that follows a black boy growing up in St. Louis.

“Whose work, right now, feels just so crucial to any sort of conversation around … speculative fiction and histories of race, slavery and colonization, (and) who put those two things in conversation with each other in a way that makes them seem really necessary for each other, just like Octavia Butler did?” Atkinson asked. “That person was absolutely John Keene, so that’s why I’m so happy he said yes.”

Approaching his lecture as “a conversation” between Butler and the context in which she wrote, Keene will link the themes in Kindred to the present and discuss the “power” of speculative fiction.

Approaching his lecture as “a conversation” between Butler and the context in which she wrote, Keene will link the themes in Kindred to the present and discuss the “power” of speculative fiction.

He pointed to the recent congressional hearing on reparations on June 19, 2019, as evidence of the book’s relevance.

“One of the responses to (arguments for reparations) is that slavery was 150 years ago,” Keene said.

Literature like Beloved, the plays of Robert O’Hara and Kindred reminds readers that racial trauma and systemic racism are alive today, he said, paraphrasing a quote from William Faulkner:

“The past is not dead. It’s not even past.”

Among the witnesses who testified before the congressional committee was National Book Award-winning writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose first novel The Water Dancer, forthcoming in September, is a work of speculative fiction with an enslaved man as its protagonist. Keene guesses that Coates, like Colson Whitehead, the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Underground Railroad, would count Butler as an influence.

“(Butler) really opened up an imaginative space for other writers to follow,” Keene said. “There were a number of African American writers and artists (in Butler’s era) writing about the past and writing about slavery. But to actually use the tools of speculative fiction to explore the topic was quite remarkable and quite revolutionary. I don’t think it has gotten a lot of recognition.”

According to Keene, Kindred is both “a signal text of afrofuturism” and “a demonstration of the emphatic power of literature.” The two central characters, Dana and Rufus, are distant relations, caring for and brutalizing each other throughout the history of their encounters. But they are, in the slaveowning South, unequally matched, and Rufus’ casual attitude toward black lives is deeply disturbing.

Through the fraught dynamic of Dana, Rufus and Dana’s white husband, Butler is “thinking through the complexities of our families,” Keene said. Fortunately, he added, Butler is “clear-eyed about the limits of empathy.”

“Her portrayal of Rufus is a way to bring the reader into a more complex version of the past,” Keene said. “We are all human.”