Over time, Scott Kelly has become “smarter and more handsome” than his identical twin brother, Mark. What’s his secret? A year in space.

With one brother on Earth and the other 254 miles above it, researchers had the unprecedented opportunity to monitor the effects of space on the human body. Now, those results are being used to determine what boundaries exist in the future of human-space exploration — because if the sky is no longer the limit, what is?

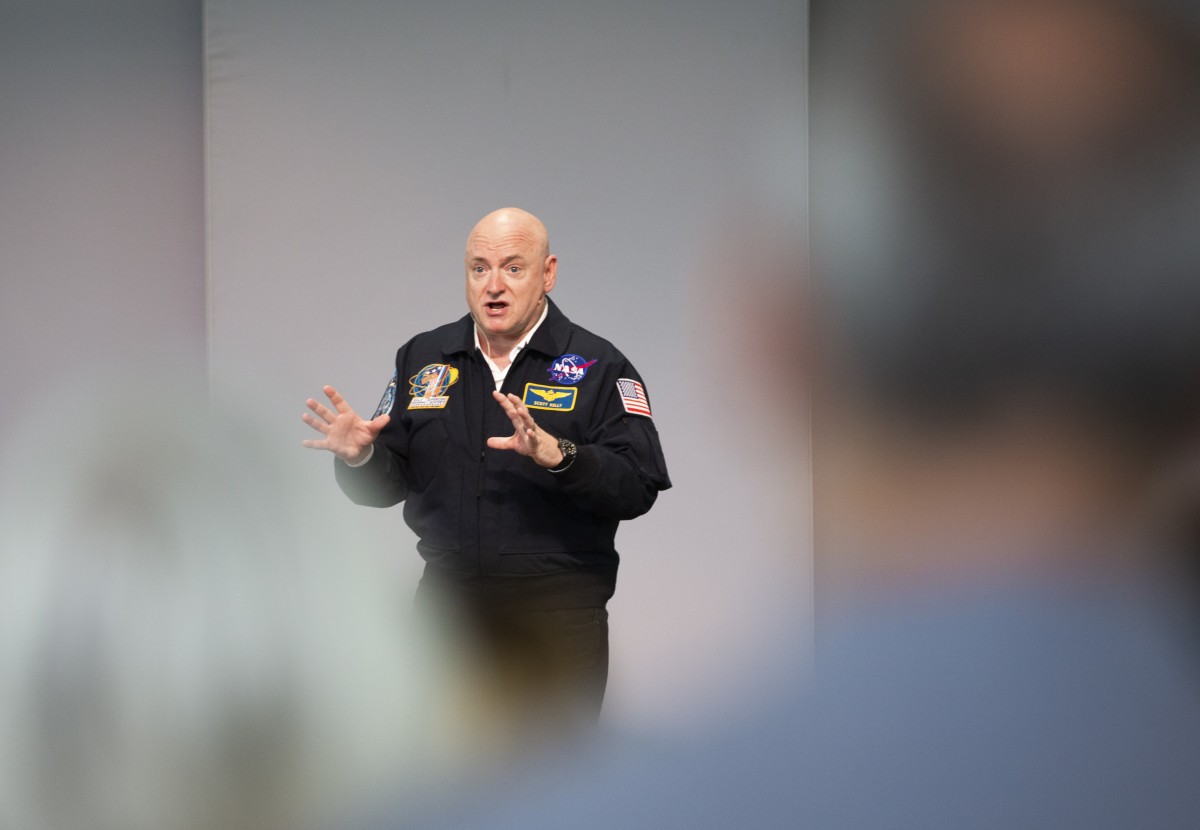

Kelly, an engineer, retired astronaut and U.S. Navy Captain, addressed that question at the 10:45 a.m. morning lecture Friday in the Amphitheater, closing Week Four, “The New Map of Life: How Longer Lives are Changing the World — In Collaboration with the Stanford Center on Longevity.” Kelly spent the second half of his lecture in conversation with Matt Ewalt, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education.

“Eventually I found inspiration in a book… it inspired me that I could potentially do more for my life,” says @StationCDRKelly

— The Chautauquan Daily (@chqdaily) July 19, 2019

Kelly grew up in New Jersey, where his mother, a former secretary and waitress, became their town’s first female police officer. In her determination, Kelly saw what it took to achieve any dream.

“This was the first time in my life that I saw the power of having this goal you think you can’t achieve, a plan to get there and working really, really hard at something,” Kelly said.

The problem was, he didn’t have any specific dreams in mind. However, after reading Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, a story documenting the first Project Mercury astronauts selected for the NASA space program, Kelly realized he had some out-of-orbit aspirations to consider.

“It wasn’t easy,” he said. “I had to take a bad student and turn myself into a good student, but, eventually, I found my way and I got commissioned into the United States Navy, became a fighter pilot, a test pilot and later, a NASA astronaut.”

Almost 18 years, to the day, after reading The Right Stuff for the first time, Kelly took his first trip into space, a trip to repair NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope in 1999. On his second mission, he crossed the threshold of the International Space Station for the first time as commander of space shuttle Endeavour. He returned to the station for a six-month stay in 2010, commanding Expedition 26.

When he returned home from his third trip safely, NASA proposed sending two astronauts for an entire year.

“Somehow they came up with me, this kid from New Jersey who couldn’t do his homework, and a guy I now refer to as my Russian brother from another mother, Mikhail Kornienko,” Kelly said.

To some, a year might seem extreme, but Kelly said the intensity of the experiment was for the sake of the future. If people should venture to Mars, a planet on the other side of the sun, the trip will take more than three years to complete.

“Never ever on the shuttle did I look outside one time…. it was only because I was focusing on things I could control,” says Kelly.

— The Chautauquan Daily (@chqdaily) July 19, 2019

“Going to Mars is going to be hard; it’s not going to be an easy thing to do,” he said. “It’s going to take a lot of risk for the crew members, it’s going to take risk of the program and risk in investment, but this is something I am convinced we absolutely have to do if we are going to continue as a species.”

In March 2015, Kelly launched into space from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, at 17,500 mph, never once looking out the window.

“It was only because I was focusing on the things I could control — the procedures, the systems, my job — and ignoring everything I couldn’t,” he said.

After six hours, he docked at the International Space Station, a solar-powered station in Earth’s low orbit. According to Kelly, life on the station is challenging, but during the year it served as his home, he found ways to improve his surroundings.

“You always have to question, ‘Why are we doing this thing this way?’ ” he said. “Why can’t we just make this system, this procedure, this operation, just a little bit better? In my experience, spending all this time in space, if we’re not always trying to make things at least just a little bit better, questioning and testing the status quo, things are absolutely going to get worse.”

The space station was Kelly’s office, too. There he conducted research utilizing a combination of biology, chemistry and physics.

“(We are) studying these things that happen to us in space that are very similar to what happens to us as we age,” he said.

In addition to using the sciences to study space, Kelly also collected data about his health to compare it to Mark Kelly’s on Earth. Ten science teams in NASA’s Twin Study examined the brothers’ bodily functions, both physically and cognitively.

“It was a genetic study about understanding our physiology and how this environment affects us at a genetic level,” he said.

“After spending a year in space I was absolutely inspired,” says @StationCDRKelly, “If we can dream it, we can do it.” pic.twitter.com/GnKeYKeLxj

— The Chautauquan Daily (@chqdaily) July 19, 2019

Regardless of where the trip leads, any time in space damages the human body.

“It’s almost like we are aging at a very, very accelerated rate,” Kelly said.

In space, humans lose 1% of bone and muscle mass a month.

“If you didn’t do anything to prevent that, after 100 months, you would have no skeleton left,” he said. “(That has) effects on our immune system, our vision and our physiology.”

With that in mind, Kelly said the results of the Twin Study were unexpected. In terms of telomeres, the ends of chromosomes that shorten and fray with age, Kelly’s hypothesis was that his would get shorter. As it turns out, his telomeres grew. In addition to his telomeres, scientists found that 7% of his gene expression changed over the course of his mission.

Cognitively, Kelly improved while being tested in space. However, after returning home, he was slower and less accurate on short-term memory and logic tests.

Along with being a scientist and a commander, Kelly wore many helmets in space. As the station’s only residents, Kelly’s team had to take care of general maintenance for the station, the shuttle and each other.

“You’re not only the scientist and the engineer and maybe the commander of the mission, you’re the electrician, the IT person, the plumber, the doctor and the dentist,” he said.

Because “all good things must come to an end,” Kelly returned to Earth on March 2, 2016. When he returned to his home in Houston, Kelly jumped in his swimming pool, had a beer and a piece of apple pie sent from the White House, and took his first shower in a year.

“All of those things were great, but the best part about coming home after being in space for a year was that I knew I had just done one of the hardest things I will ever have to do in my entire life,” he said.

Although he felt accomplished mentally, Kelly wasn’t doing well physically; he had trouble standing up, he was stiff, sore, nauseous and dizzy, and developed rashes and hives when his skin touched any surface.

All of those ailments went away with time, but what he learned in space has always stayed with him.

“NASA doesn’t really see any long-term showstoppers for going to Mars,” Kelly says.

— The Chautauquan Daily (@chqdaily) July 19, 2019

First, Kelly learned the value of teamwork.

“When we’re trying to do anything that’s challenging or difficult, you’ve got to do it as part of a team,” Kelly said. “I say space flight is the biggest team sport there is.”

Second, he learned about the importance of diversity in those team activities.

“It wasn’t until I got to NASA that I saw the power of having a group of people working together that come from different places, different experiences, different cultures and different ways of looking at things,” he said. “When you have people who look at things differently, they have different solutions to problems, and that’s what our job is, to solve problems.”

Third, he gained a new perspective on Earth’s environmental issues. From space, Kelly can see that certain areas in Asia and Central America are covered by air pollution. Between his space missions in 1999 and 2016, he also noticed a vast difference in the size of rainforests around the globe.

Kelly said there is a misconception that moving to another planet is a solution to Earth’s problems.

“We are not all going to Mars, I hate to tell you,” he said. “It will always be easier to live here, no matter how bad we destroy this planet, than it will be turning Mars into another Earth.”

The space station, where Kelly has spent over 500 days of his life, is a 1 million-pound, football field-sized structure that was created by people all over the world. By its very existence, Kelly learned that anything is possible.

“After spending a year in space, I was absolutely inspired that if we can dream it, we can do it,” Kelly said. “(We can do it) if we focus on the things we can control and ignore the things we can’t, if we test the status quo, and of course, if we work together as a team. Teamwork makes the dream work. We can choose to do the hard things and if we do that, the sky is definitely not the limit.”

Kelly ends by saying, “It’s hard to believe that we have so much potential, yet we sometimes treat people from other countries like they don’t matter.”

— The Chautauquan Daily (@chqdaily) July 19, 2019