David W. Blight does not remember learning about Frederick Douglass in high school.

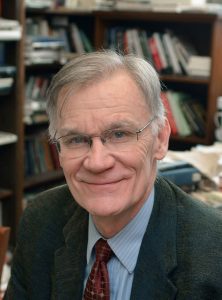

As a college student in the late ’60s and early ’70s, the current director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University, recalls some mention of Douglass. But it wasn’t until he was creating his own courses in black history as a public high school teacher in Flint, Michigan, and later pursuing his graduate degree in the late ’70s and early ’80s, that Blight properly encountered the man whose name and likeness graces the cover of his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography.

“I just remember thinking, ‘Who is this guy?’ ” he said.

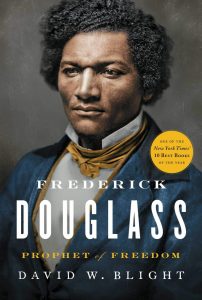

Blight will give the second Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle author presentation of Week Two, a lecture on his biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom at 3:30 p.m. today, July 4, in the Hall of Philosophy.

The lecture is co-sponsored by the African American Heritage House, and holds a particular resonance for a talk on the life and legacy of the great American orator, as Douglass delivered his seminal speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” on July 5, 1852, in Rochester, New York, about a two-and-half-hour drive from the Institution grounds.

At 888 pages, Frederick Douglass is the result of a decade of work and the culmination of Blight’s career as a professor and public historian. Although they received recommendations “on a lot of well-reviewed, mammoth biographies,” Atom Atkinson, director of literary arts, said Blight’s stood out, not only for the potential of a CLSC lecture on the Fourth of July, but also for Blight’s command of language.

“For how long it is, it’s also quite cinematic and quite entertaining,” Atkinson said. “That’s not something you can say about every biography of a major U.S. historical figure.”

So central is Douglass’ own command of language to Blight’s biography that the author describes his book as a “biography of a voice.” (He even considered that as a title, but was quickly vetoed by his editors). Unperturbed, Blight ensured that Douglass’ voice and “genius” with words remained a primary theme, as Frederick Douglass follows its subject from his birth as an enslaved child in Maryland, through his rise as a fierce advocate of abolition and social reform.

“Douglass was a creature of words,” Blight said. “He wrote millions of words. Words were his weapon, his power.”

Frederick Douglass’ page count might be daunting, but it’s a testament to a life spent writing, and it dwarfs in comparison to the boxes in which Blight stored his research.

Characterizing himself as “a paper person,” Blight acknowledged that his writing process involved “a lot of printing” and that his organization system was “at times a bit haphazard.” He took “pounds of paper” with him when he served as the William Pitt Professor of American History at Cambridge University, and wrote at the speed of a chapter a month.

Similar to the time he spent getting to know New Bedford, Massachusetts, and the environment of Maryland’s eastern shore, traveling in the United Kingdom was a chance to situate himself where Douglass lectured against slavery — visits, Blight said, that helped him “gain a sense of texture.” Still, packing up his notes and flying them across the ocean was a nerve wracking lesson in letting go.

“I remember thinking, ‘Well, there’s my career heading over the Atlantic,’ ” Blight said. “ ‘Hope it gets there.’ ”

The first dedication of Blight’s book is to Walter O. Evans and Linda J. Evans, the owners of a private collection of Douglass material — including 10 family scrapbooks — that illuminated the last third of Douglass’ life. Blight spent “four or five” spring breaks from Yale in the Evanses’ home, poring over new details about Douglass’ role as a Washington insider and steeped in the letters that fleshed out Douglass’ “very complicated” extended family.

“One of my proudest moments has been when people have told me, particularly women historians, that they so appreciate the way I handled Anna Murray-Douglass,” Blight said, referencing his book’s portrayal of Douglass’ first wife, the mother of his four children and a woman about whom he wrote little in his three autobiographies.

Unafraid to explore the messier, less heroic aspects of Douglass’ life, Blight admits there are elements of the book he would like to do over. After giving more than 100 interviews and talks as part of a promotional book tour, he discovers new information about Douglass frequently. His decision to conclude his biography with an epilogue about Douglass’ death and its immediate aftermath was purposeful; delving extensively into the man’s legacy would require, according to Blight, “another book.”

“A life is lived in the order it happens,” he said. “It’s not necessarily how you remember it. But I think that’s why the biography is still so attractive to readers because they are reading about a structure of a life at the same time they’re reading about a changing life through time.”

Frederick Douglass is an encompassing journey through that life — a portrait of survival, endurance and supreme literacy. With multiple book prizes and honorary doctorates to his name, Blight may be a celebrated public figure himself, but he likes to think of himself as “a teacher first.”

“I was a high school teacher who just wanted to see if I could become a scholar,” he said. “It took time, but I managed to do it, I guess.”