As a religious naturalist, Michael Hogue doesn’t think humankind is the center of the universe.

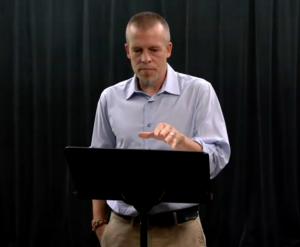

Hogue opened up the first of Chautauqua’s 2020 Interfaith Friday lectures with how centering nature as a religious naturalist has shifted his perspective. Gene Robinson, Chautauqua’s vice president of religion and senior pastor, joined him in this live virtual conversation at 2 p.m. EDT Friday, July 3, on CHQ Assembly. Audience members also participated by submitting questions through the www.questions.chq.org portal and through Twitter with #CHQ2020.

The Department of Religion’s Interfaith Friday series asks questions from each speaker that consider how their faith traditions describe creation, God, how humans fit into the universe and how they view humankind from their vantage point.

Religious naturalism is the wild and wonderful other side of spiritually and emotionally domesticated ways of thinking, Hogue said. It’s not intended to be anti-religious, just open to all influences, including science and philosophy.

The story of creation follows the science of evolution, he said. Nature is beyond God. Humans are not the center, but morality and justice are the work of humankind.

Religious naturalism was first developed in the Chicago theological school of thought in the 1940s, said Hogue, who is a scholar and professor at the Meadville Lombard Theological School in Chicago, Illinois.

Throughout his life, his view on how humans occupy nature shifted twice. The first time was when he saw a distant smudge on the water in North Michigan that made him hold his breath before it inched closer and closer, unfurling into rain moments later. Then later, when he returned to North Michigan as a college student of philosophy. He was driving around North Michigan with his cousin and pointed out where his friend’s cherry farm used to be before climate change’s early thaws and late freezes had weakened the multi-generational farming community, and before real estate agents had subdivided the land into “McMansions.”

“What used to be there before the orchards?” his cousin asked.

Hogue felt displaced.

“The land and people on the peninsula were continuously changing,” Hogue said. “And if this was the case, if everything was always changing, then on what basis was I arguing that the orchards and farming community, who, after all, were descendants of white settlers who had harvested forests and taken land from the Ottawa, were morally preferable to the front yards of affluent downstaters?”

Nature itself is the focus of religious naturalism, but nature itself has no center or intrinsic meaning other than what humans have assigned to it.

Hogue said the scale of the universe calls human-centered religion into question, so all levels of life are included. The drive of animals to live — hunt and forage for food, find water, care for their kin — puts them on the same plane as humans.

Religious naturalism does not have a harmonious vision of nature, Hogue said. It is beyond good and evil. There is predation and homicide in nature, but there is also birth, family and the joy of sharing a meal. Observing and reflecting on nature, he said, does not mean that we should pull lessons from nature to think about morals and ethics.

“We have to avoid what is called naturalistic fallacy — there is no reason to mimic nature,” he said. “We cannot navigate a moral dilemma informed by how we think nature works. Morality is a human practice.”

Moral stories and systems emerged out of prosocial tendencies, which Hogue said people “reified” and used to compare their institutions with those of other groups.

“We survive together by dividing ourselves and reinforcing the validity of our stories compared with other groups,” Hogue said.

There are unanswered questions in religious naturalism that Hogue and others of the faith have to accept.

“Why the universe exists will forever remain out of reach for us,” Hogue said. “The question of God’s existence is not a question that naturalism tries to solve.”

However, sin does exist in terms of elevating one’s self, a group or even a nation above the rest. An inability to consider others above ourselves goes against the task in religious naturalism to take the responsibility to help and lift up others.

Robinson asked if Hogue ever felt guilt, and what he does about it.

“Of course I feel guilt,” Hogue said. “I sometimes ask for guidance for life from the universe, from mystery. … I don’t live up to my ideals, but I actively work toward them in daily life.”

And what is love?

“There are no pre-existing reasons for why we love others,” Hogue said, while acknowledging the prosocial tendencies he mentioned before. “Loving your kids provides a reason to care for them.”

And what makes a worthy life?

“All life has inherent worth, dignity and value,” Hogue said. “A life to be praised is one that lifts others up and is committed to ensuring a world that honors that.”