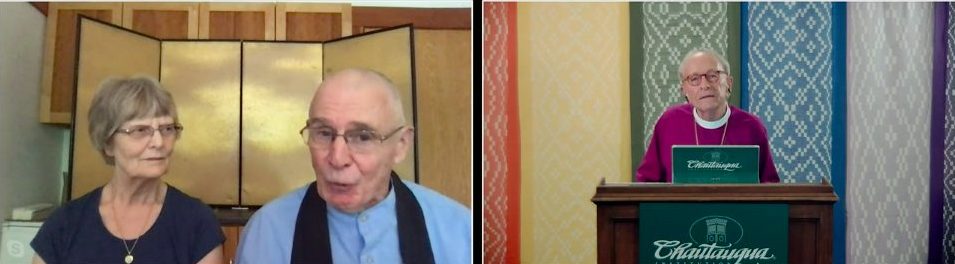

Wayman and Eryl Kubicka answered questions about creation with their “non-understanding of creation” as Zen Buddhists For Week Three’s Interfaith Friday.

The lecture was broadcast at 2 p.m. EDT Friday, July 17, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform. Audience members also participated by submitting questions through the www.questions.chq.org portal and through Twitter with #CHQ2020. Gene Robinson, Chautauqua’s Vice President of Religion and senior pastor, joined in the live virtual conversation and delivered audience questions.

Eryl and Wayman have taught Buddhist meditation in Chautauqua’s Mystic Heart Meditation Program for 10 years. Wayman, an ordained Buddhist priest since 2010, runs the Rochester Zen Center’s retreat in New York, teaching meditation and overseeing training. Eryl teaches meditation and coordinates the youth program for the center.

They each became interested in Buddhism and meditation before meeting each other in the province of Quang Nyi in Vietnam. Wayman was part of an American Friends Service Committee (Quaker) team located there to build and run a rehabilitation center for injured civilians.

Eryl met Wayman when she joined the team in 1969 as a physical therapist and practicing Buddhist. They were married in 1970, and have practiced Zen meditation for four decades. They first studied under the guidance of Roshi Philip Kapleau, who helped Wayman with post-Vietnam PTSD through meditation, and under the current abbot, Roshi Bodhin Kjolhede.

Wayman began the lecture with the opening story from Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time: an old anecdote where an elderly woman speaks up at the end of a prominent astronomer’s public lecture. She tells him his understanding of how the universe works — the moon revolves around the Earth, which revolves around the sun with other planets, while various galaxies exist far and wide — is not true, because the world is flat and rests on the back of a turtle. The astronomer asks what the turtle is standing on, and she says, “‘You’re very clever, young man, very clever. But it’s turtles all the way down.’

“Why do we think we know better than that?” Wayman said.

Zen Buddhism is about being content with not knowing all the answers.

“I think most Zen Buddhists would affirm that we do not, and perhaps cannot, know very much about the universe, and what ultimately could be behind this creation,” Wayman said. “Of course, this doesn’t mean there isn’t a great deal of scientific thinking or religious thinking that cannot tell us what is likely true, and what is exactly not true, and especially what is of value.”

Being content in the present while accepting change is another priority in Zen Buddhism.

“Regarding creation, we can probably surmise that nothing will stay as it is forever,” Wayman said. “But that does not likely apply to laws that govern change, development and interaction. Personally, it has become more clear to me that I will not be around forever.”

Wayman turned to science to fully answer questions about creation, citing astrophysicist Ethan Siegel, who said that from a symmetrical universe, nothing after the Big Bang happened broke up in equal amounts. An excess of matter was created, but the existence of anti-matter is still an unanswered question.

“Until (technology reveals otherwise), we can be certain that there is no anti-matter in the universe, but no one knows why,” Wayman said.

Wayman said that for non-Buddhists, many Zen Buddhist teachings can be confusing and can feel like the turtles mentioned in Hawking’s story. He dropped common sayings from fundamental Zen Buddhist writings like, “Form here is only emptiness, emptiness only form;” and, “Feeling, thought and choice. Consciousness itself is the same as this.”

Emptiness is a state to be achieved in Zen Buddhism.

“Here are empty all of the primal void,” goes a Zen Buddhist Dharma, or a teaching. “None are born or die, neither stained or pure. Nor do they wax or wane.”

Zazen samadhi is an awakening experience in Zen Buddhism in which a person releases their ego.

Wayman said it is achieved through “constant meditation and prayer to the point of complete self-forgetfulness. It takes years of work in meditation.”

While this is given a name within Buddhism, the faith does not own this state exclusively. Wayman mentioned Byron Katie as a secular American author who describes how she has achieved this herself. And Christians might describe this same feeling as the love of God.

Wayman and Eryl were exposed to Zen Buddhism later in life. Eryl grew up in the Church of England while Wayman grew up in a Unitarian Church in Chicago. But recalling the message on the ceiling of his Sunday school, “God is love,” Wayman said there are similarities.

“I don’t think we’re at a different place here in Buddhism,” Wayman said.

Robinson inquired about the geographic differences in Buddhism practices, specifically between the East, where it originated, and in the West as a budding practice.

“The tradition is monastic, so that already sets the stage for a certain kind of practice,” Eryl said. “But each time the tradition moves to a new culture, it has to adapt. That’s still in the beginnings here in America, of Buddhists learning how to mix the lay-practice, because that’s really mostly what it is here.”

There are varying levels of seriousness in Buddhists who live where Buddhism is common, which is similar to how Christians who grew up in faith communities take it less seriously or forgo it as adults.

In the West, meditation has become a big draw for new Buddhists, and Wayman said it’s because meditation works.

“You see the difference in your life,” Wayman said. “How you respond to problems, how you can handle others, and the ease with which you can feel other people with all those things that used to be difficult, now become easier and easier as you practice meditation.”

Meditation helps return to a silent mind.

“(Letting thoughts settle) gives you a gap,” Eryl said. “Let’s say you get angry. You have a little, one tiny centimeter of time when you can choose whether you react or you respond.”

Wayman noted that meditation and praying had similar uses of re-centering a person back to their original silent mind.

Robinson agreed, recalling when a spiritual director had told him that before praying, he should imagine he’s getting on a bus and forgot to get off on the right stop. So he has to get out, return to where he started and “wait for God.”

The difference between Buddhism and Christianity, the Kubickas said, is that Buddhism is better defined as a practice.

“We don’t have stuff we need to believe in, but we do need to work on becoming quieter,” Wayman said. “That’s the work.”

Eryl also said that being kind to oneself during meditation or prayer is also important.

“When you retrace your steps to the bus stop, you don’t want to be criticizing yourself,” Eryl said. “Because that judging mind is always there waiting to say, ‘Oh, you’re such a poor meditator.’ That’s the tricky little gremlin up there.”

Concentration of the mind, and as Wayman says, discarding of “random thought-ing,” is the purpose and practice of meditation. One way to achieve this is by focusing on a word and nothing else.

Robinson said this would be personally difficult for him.

“It’s like telling someone not to think about their nose and that’s immediately where their mind goes,” Robinson said.

This got a laugh from the Kubickas. They also suggested following the breath and counting breaths in meditation to focus.

It’s terribly important to be present with everything and not to escape with your thoughts,” Wayman said. “Be present with pain. Be present with love. Be present with talking with somebody. Be present with walking the dog. Be present with lifting up a glass to drink. That’s the way we work on living.”

Robinson asked about personal responsibility to others in Buddhism, since meditation is often practiced on an individual level, but can also be used in social causes such as climate change and the Black Lives Matter movement protesting police brutality.

Buddhists also practice group meditation, and also have a duty to help others since everything is seen as being interconnected.

“There is no duality in Zen Buddhism,” Eryl said. “So if we’re all one, then you cannot ignore, you can’t be indifferent. Pragmatism and indifference can just be another way of avoiding what you should be doing.”

The same goes for dealing with tragedy.

“It’s terribly important to be present with everything and not to escape with your thoughts,” Wayman said. “Be present with pain. Be present with love. Be present with talking with somebody. Be present with walking the dog. Be present with lifting up a glass to drink. That’s the way we work on living.”

Eryl pointed out that the only symbol in Buddhism is the circle, which represents oneness between all beings, including those that are not human.

“If we are the divine nature, not as a god concept, but if we are the divine nature, we’re all connected,” Eryl said. “And so everything is interrelated, interconnected, and so what happens to you actually happens to me, too.”

The final enlightenment in Zen Buddhism is that nothing exists. A question came in from the virtual audience that brought an understanding to the concept of “nothing.”

“Might Buddhism infer that ‘nothing’ is the foundational reality that other traditions feel the impulse to call God?” the questioner asked.

To the Kubickas, enlightenment as defined in Buddhism can be achieved through other belief systems.

“Fundamentally, it’s the same mystics,” Eryl said. “It’s where all the same streams lead into the ocean somehow.”

The concept of time, beginnings and endings is seen in a new light in Zen Buddhism, which includes the belief in rebirth and emphasizes the importance of the present moment.

“Everything is in flux,” Eryl said. “We’re like energy in flux, and so change is our nature.”

Robinson said Buddhism’s emphasis on staying present reminded him of how he guides couples through pre-marital counseling. He tells couples that his goal is “for them to be present in their own wedding” without worrying about small details like flower arrangements or how people in the crowd might feel while they’re at the altar.

“It seems to me that Buddhism invites each person to attend each moment,” Robinson said.