For the Rev. Willie James Jennings, sin — racism, sexism and weapons of mass destruction, to name a few — is defined as a misalignment of gospel.

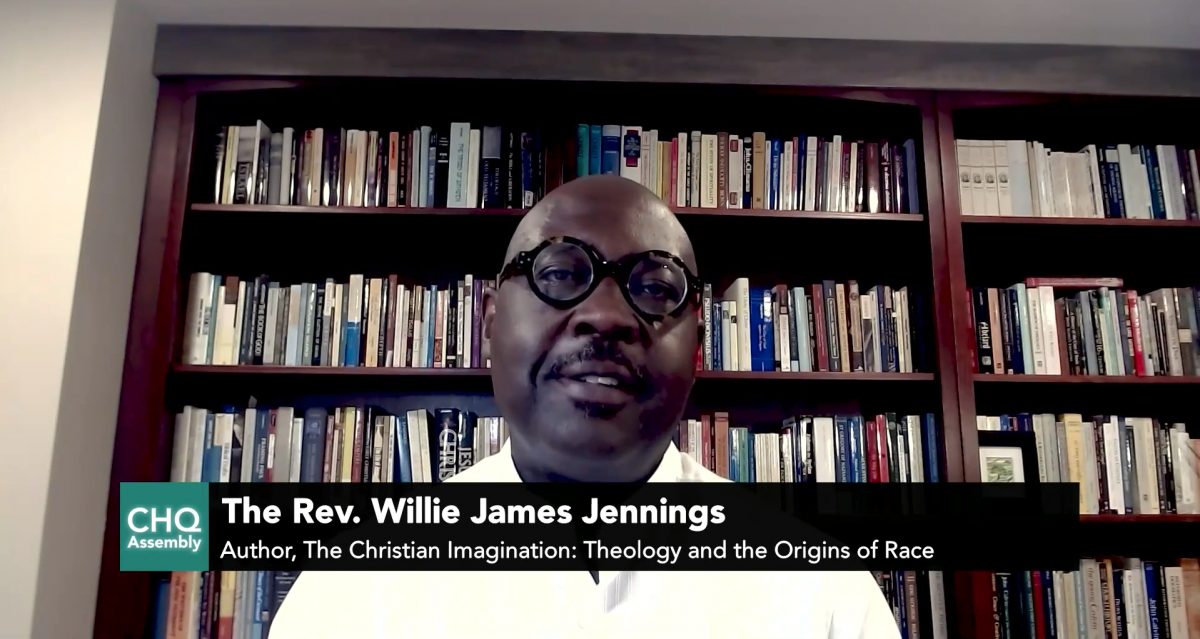

Jennings represented the perspective of Evangelical Christianity for Week Two’s Interfaith Friday on July 10 for CHQ Assembly. Audience members also participated by submitting questions through the www.questions.chq.org portal and through Twitter with #CHQ2020.

Jennings, associate professor of systematic theology and Africana Studies at Yale Divinity School, is the author of several books, including The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. In 2015, he received the Grawemeyer Award in Religion for his work on race and Christianity, and most recently his written commentary on the Book of Acts won the Reference Book of the Year Award from The Academy of Parish Clergy. His forthcoming book, After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging, will be published in October 2020.

Citing the Nicene Creed, Jennings said Christianity in all its forms has emphasized the relationship between humans, God and Jesus. Jennings made a point to differentiate Protestant Evangelical Christianity from the sort of Evangelical Christianity that Jennings said had negative interpretations in political and social spheres.

Gene Robinson, Chautauqua’s vice president of religion and senior pastor, joined Jennings in the live virtual conversation.

“I consider myself an Evangelical, which makes most Evangelicals’ blood run cold,” said Robinson, the Episcopal Church’s first openly gay bishop.

In Protestant Evangelical Christianity, the good news, or gospel, is directly tied to God creating the world and humans in his image.

“God created us out of love,” Jennings said. “Not out of compulsion, not out of necessity and certainly not out of arbitrariness.”

To maintain God’s creation is to keep a relationship with God. But it’s possible to step outside the bounds of this relationship.

“Of course, the struggle for us is how to live a relationship that aligns with the loving and life-giving reality of God,” Jennings said. “What we call sin … has to do with this misalignment.”

Misalignment, or sin, is using God’s gift of creation for destruction. Jennings said European colonizers were a major example of this.

“(Europeans) looked out into the world and imagined it as a resource given to them by God,” Jennings said.

Jennings said weapons are another high-level form of misalignment.

“(The existence of weapons) reshapes the social landscape of the imagination,” Jennings said. “A world awash with guns is a world already bent toward fear and violence.”

And both guns and weapons of mass destruction are a reckoning not just for the Christian faith — they point “not only to a weakness in our faith traditions, but a crisis in our belief in a god who creates,” Jennings said.

Even without a crisis in belief, Jennings said God and his creation — including humanity — should still be both a mystery and joy that doesn’t need to be solved.

But the concept of flesh in the Bible has been a source of pain for Black and indigenous people. Jennings said in the Gospel of John, the apostle — a subordinate to Jesus — was not the light but gave witness to that light. This introduction to the treatment of people based on status in the New Testament communicated to people of color that perhaps God had ignored them.

But in Genesis in the Old Testament, however, the story of creation placed all people as equal and important in a “profound, society-breaking, oppression-breaking” affirmation.

The concept of flesh in Christianity changed throughout time. Jennings said there are two levels of its understanding: the flesh and body as a symbol of weakness, and the flesh as an indication of how a larger system treats someone.

“It’s an indication of a wider system … in which the body is captured in political, economical and social forms of oppression and subjugation,” Jennings said. “The Gospel comes to free us from this.”

Fundamentalist Christian thought collapses the two definitions. But Jennings said that in the Christian faith, God frees people from the suffering of flesh by entering the world of the flesh through Jesus to free people from subjugation by going through suffering himself.

“Gods (in many religions) with any sense at all certainly didn’t want to become human,” Robinson said. “The fact that God does, and did (through Jesus), is shocking.”

Sin is also often described through a weakness in flesh.

“The way of the flesh is a life out of control, a life enslaved,” Jennings said. “The creation of race would not have been possible without Christianity. People still think it is as natural as biology. For many people, the word ‘race’ can be replaced with ‘culture’ (and vice versa).”

Jennings said much of sin is tied to not being able to exist in a shared world and undermining an innate connectivity.

Police brutality is an example of this sinful disconnect.

“The way whiteness has formed in some people has caused a deep disconnect from their environment and their world and from other people,” Jennings said. “What drives policing is fear of the ‘other.’”

Diving into the history of how lands have been taken on a local and global level is one way to counter this disconnect.

“We tend to operate in what I call harmless history,” Jennings said. “It’s the history of the heroes, the powerful men. ‘They had their warts, they had their weaknesses, but look at what they accomplished.’ That harmless history is always going to thwart the depth of listening.”

For a person to think they know everything about other humans, he said, is also a disservice to this process of listening.

“The danger is to mistake apprehension with comprehension,” Jennings said. “What’s necessary is a lighter touch that most people in the West don’t tend to have.”

Returning to the Nicene Creed, which denoted a shift in how humans’ understanding of the word of God changed, Jennings and Robinson agreed the council meeting that created the creed was evidence of God’s struggle with creation’s inability to comprehend his meaning.

Robinson said Chautauqua Institution itself has its own reckoning to do in how the ratio of diversity among its speakers is greater than the diversity of viewers in its audience.

“Racial segregation is a highly skilled, profoundly cultivated practice of our collective life,” Jennings said. “No all-white community — or predominantly white community — happened by accident. It happened through a relentless cultivation of segregation. Quietly, subtly, but consistently. Which means that it cannot be overcome without an intentionality that presses in the opposite direction of that subtle, relentless cultivation.”