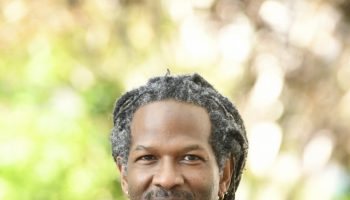

Meria Carstarphen experienced first-hand as a Black student how the American public education system exacerbates systemic racism in the classroom. This is why she has dedicated her career as an educator to serving the children who are — like she was years ago — an afterthought in the education system.

“I was in high school into the late ‘80s. I went to school (in Selma, Alabama) through a tracking system where once you were in — often based on socioeconomics and race — honors classes, you had access to rigor and education,” Carstarphen said. “Basically … it was who you were, not what you knew, that might give you access to those opportunities. Growing up in public education, I was always one of less than a handful of Black kids in any of my classes.”

Carstarphen returned to her hometown to teach middle school Spanish and documentary photography and saw the same systems of oppression shaping the next generation. She wanted to make a bigger difference — so, she went to Harvard for a doctorate specializing in superintendency. With this, she served in three capital cities across the nation — St. Paul, Austin, and most recently Atlanta.

“I believe public schools are the canary in the coal mine. If you use your public school system, which is the gateway for anybody to get educated, to have a mind that thinks for itself, and can make decisions for itself — if you’re not doing that for everyone who walks through a schoolhouse gate, then you are literally undermining the very democracy we’re trying to preserve.”

“Before, (education inequality) was driven by laws and rules and social behavior — but today, (education inequality) is driven by housing patterns and socioeconomics. Those systems separate kids,” Carstarphen said. “You, (a student), can go to school your entire public education career and never … from pre-K to 12th grade (go to school) with a white person in the building.”

The solution to this isn’t a simple Band-Aid. Carstarphen believes that the best approach to reforming education is to reconstruct it from its base.

At 3:30 p.m. EDT, Wednesday, Aug. 5 on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform, Carstarphen will present “The New Reconstruction: Transforming Education for the 21st Century,” the Week Six lecture in the African American Heritage House lecture series.

“I believe public schools are the canary in the coal mine. If you use your public school system, which is the gateway for anybody to get educated, to have a mind that thinks for itself, and can make decisions for itself — if you’re not doing that for everyone who walks through a schoolhouse gate, then you are literally undermining the very democracy we’re trying to preserve.”

In her experience as an educator, Carstarphen has solidified her belief that a fair education system that serves all students is essential to a democracy. She pulled much of her lecture’s argument from an 1866 essay by Frederick Douglass on Reconstruction.

Reconstruction was a period of 12 years following the Civil War in which the United States had to rebuild a system that included 4 million formerly enslaved people into the fabric of society. Many positive changes came from this era, ncluding the establishment of Black institutions like Howard University. However, state legislatures in the South built an unwelcome system for Black people, writing “Black codes” that restricted the labor and behavior of freed slaves.

Carstarphen found that during this era, narrow expectations and practices for education were established that still exist, in one way or another, in 2020.

“The idea of Reconstruction … is a great vision, but what is missing is a process that was inclusive in the first place — a process that gave those very people who were marginalized and enslaved real agency in shaping the society that they were trying to build, so someone else built it for you,” Carstarphen said. “The people who had the power, the control, the voice, driving Reconstruction — the white elite — are the very same people who had all the power, the control, the voice before Reconstruction. It’s only natural that (this) exclusive process reproduces exclusive power structures, which is why we struggle today.”

Systemic racism exists all around American cities — not just in the classroom. Carstarphen saw first-hand in her time as an educator that certain neighborhoods and communities were invested in while others were not. Oftentimes, the neighborhoods that were left in the dust were overwhelmingly Black.

“You can go back and see how the vestiges of past behavior still are implemented today — but it’s a new kind of (repression). You see where massive tax breaks are given for development in the hottest areas of a city. Cities give the tax breaks, and they often take from public schools (or other services) to do that,” Carstarphen said. “You’ll never see them go down and develop a Black community. Like in food deserts, quality housing, health care and clinics — those (investments) don’t exist in the neighborhoods where our kids go to school.”

Not only does this put certain communities at a disadvantage materially, Carstarphen believes that it puts a strain on a child’s psyche.

“What (the kids) experience is a reinforced message that you will not be invested in, that we do not care if you get food or health care,” Carstarphen said.

Carstarphen argues that the solution is in a complete reconstruction of the education system, including a change in culture.

“If you don’t change the culture — (the culture will) eat your strategy for breakfast every day. That’s exactly what happened in Reconstruction. Not too long (after slavery) the very people who created the systems (of slavery) were building the new system. So, they just made it so that Jim Crow laws, segregation, and the Ku Klux Klan were allowed to exist,” Carstarphen said. “You can’t go from Civil War to civil rights to now civil unrest. At some point, you have to actually say, ‘We have to come together as a collective spirit to not just change the laws, practices, and social behaviors,’ … and then commit to a new way of behaving.”

Carstarphen is familiar with educational culture change. In 2014, Atlanta Public Schools welcomed Carstarphen on the heels of one of the largest cheating scandals in public school history, where a number of teachers were caught modifying their students’ scores on standardized tests. In the following years, a number of teachers, testing coordinators, and administrators were arrested and convicted for racketeering.

“To me, this isn’t just systemic. This was done at the hands of Black people, too. It’s not all racism — some of it is racism, some of it is systemic racism — but some of that was done by the hands and the behavior of the very people who look like the children we’re trying to help the most,” Carstarphen said. “Enacting a culture change is essential.”

When Carstarphen began her role at APS, she worked to eradicate the existing culture that stressed the importance of high-stakes testing. She then created an environment that stressed the wellbeing of the students in her district — all 50,000 of them. Her first graduating class, the class of 2015, had a graduation rate of 71.5%, which was 12 percentage points higher than the previous year. In the years following, the graduation rate hit 79.9% — a historic high for the district.

In September 2019, the Atlanta Board of Education voted to not extend Carstarphen’s contract, which expired June 30, 2020. Carstarphen spent her final year at the district helping her students and 6,000 employees through the pandemic-induced shift online. Here, Carstarphen learned more about how disparities in technology and internet-access exacerbate the class issues that already existed.

“I can name 10,000 kids who don’t have technology … (or) don’t have access to the internet. It’s a new barrier that no one is addressing. To me, (internet access) is as important as water these days,” Carstarphen said. “When you go and get … a home, you don’t put up the pole and the wire for electricity. The sewage is already laid in the street with a thing that goes into your house — you don’t go dig the ditch and install.”

Carstarphen said that she was excited to share these ideas of educational reconstruction for the CHQ Assembly. As a superintendent, having abstract conversations about educational systems was a difficult thing to do.

“I’ve been in urban education for 15 years or so, and you don’t ever get to do this kind of reflection or these kinds of talks. Most people want to just hear about what we should do, should we volunteer at our school,” Carstarphen said. “I like to have a thought partnership with people who really care, and believe in this kind of discourse. But, in a respectful way, you don’t see that in our country anymore.”