NICK DANLAG – STAFF WRITER

Social media has a unique phenomenon: Even though technology allows people from across the world to connect, it has ultimately fragmented society’s interactions.

And this isn’t unique to Facebook, Twitter or other platforms. Even the telegraph and the train, technologies that allow humans to travel great distances, create psychological distance, in the same way people yell at each other during traffic.

Deb Roy, executive director of the MIT Center of Constructive Communication, said this phenomenon is partly due to the lack of negative feedback loops on social media. He said these feedback loops are vital for society because they make people aware of mistakes they make and provide them an opportunity to improve. But now, many people only become aware of their mistake when it is too late.

“(Social media) breaks down that ability to self-regulate, but it doesn’t mean there are no consequences,” Roy said. “It just means the negative signals are diffuse and the actors are not aware.”

As well as working at the center, Roy is a professor of media arts and sciences at MIT and a visiting professor at Harvard Law School. At 10:30 a.m. on Thursday, July 15 in the Amphitheater, he presented his lecture, titled “Social Media and Democracy,” as part of Week Three of the Chautauqua Lecture Series’ theme of “Trust, Democracy and Society.” Roy discussed how social media has caused societal fragmentation and degradation of human interactions, and laid out a way forward using a new technology he helped develop. That technology has already proved its worth by forging local connections across the country and assisting in a police chief search in Wisconsin and the mayoral race in Boston.

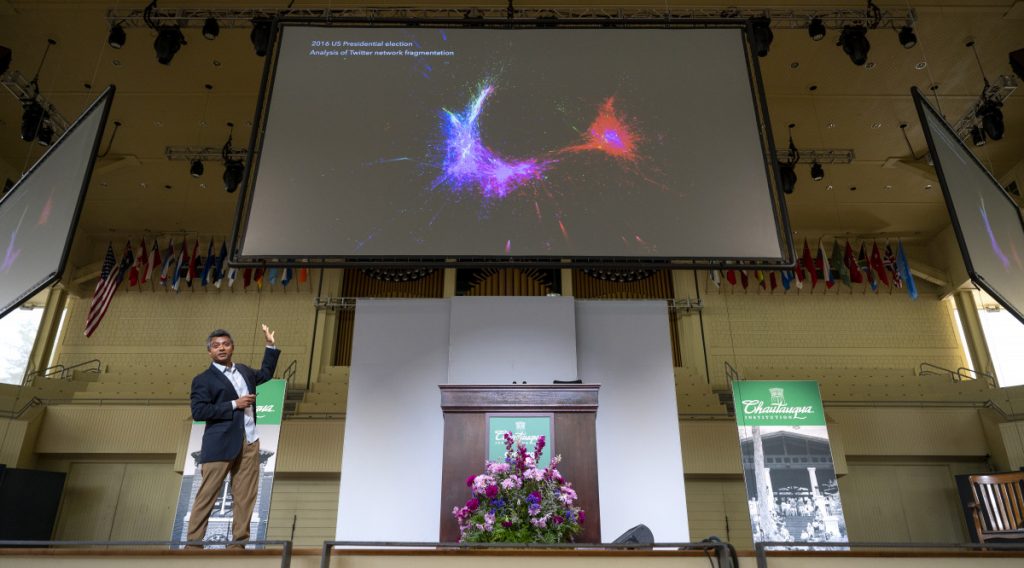

Roy wanted to know how exactly people tend to interact on social media. So in 2015, using artificial intelligence, he helped create a map of every single mutual follow on Twitter. The graph looks like a circle on one side and an-almost crescent shape on the other, with little connections between.

The circle, colored red, represented people who followed President Donald Trump’s account. This group had little mutual follows with people outside the circle, but many connections with others in the circle. The first part of the crescent were people who followed multiple candidates, and the second was Hillary Clinton followers, who were much less connected compared to Trump followers. The last portion of the crescent was Sen. Bernie Sanders’ followers, who had quite a few connections with Trump followers. Then, Roy and his team marked the public Twitter accounts of thousands of journalists; even the most right-leaning of them, some who worked at Breitbart News Network and Fox News, were not in the circle of Trump followers. Roy said part of the many journalists’ surprise at the results of the 2016 election stemmed from the mass fragmentation.

And there is a lot of toxicity and divisions within the social media platforms. One of Roy’s colleagues had particular problems with an online troll. His colleague is a Muslim woman of color, and this troll was relentless, saying phrases that the colleague wouldn’t repeat to Roy. She eventually figured out the troll was from Kansas and offered to get lunch when she was passing through.

And, as she sat in the restaurant, a mother of two wearing a cardigan walked in and sat with her.

“After a few awkward words of exchange, they entered into a real conversation,” Roy said. “They talked about their lives, about their jobs.”

The mother stopped her trollish ways — for five weeks.

“It’s a sad ending, but I share this story with you to make two points. The first is: same two people over Twitter versus in person — what a different outcome. Maybe there’s just a little glimmer of a (personal connection) that emerged in that lunch, and it actually had an effect for weeks,” Roy said. “The second is one-time interventions, one-time fixes won’t do it. We have to actually create new life habits.”

So if singular interactions don’t cut it, how can people forge connections in the age of social media? Roy said it starts at a local level, “a place that we can make substantial change.”

To forge these connections, Roy helped develop technology and a practice that helps bring people together, instead of driving them apart. Roy and the center paired small group meetings with engaging with local leaders and their own invention. It’s called a Digital Heart, a device that transcribes conversations and sorts the audio based on topics, such as education or fear of police. During conversations, the facilitator will search for audio from another recording about the same topic, effectively bringing a new voice and viewpoint into the discussion. Then the participants will respond to that viewpoint. Roy shared a recording of one such interaction this technology spurred in the town of Madison, Ohio. This is from a teacher, who is white, in Madison:

“My experiences with officers in the schools is that they do everything they can not to arrest kids,” the teacher said. “They’re extremely kind and very, very, very positive role models for kids in schools. The schools I’ve worked in, some of the resource officers are people of color, and they’re working with students of color, and they’re able to see a police officer in a responsible role, being good with kids, being supportive.”

A facilitator of another conversation asked their participants, who were all formerly incarcerated men, to respond to this quote.

One man said he couldn’t see how police in school were effective. He said when he was a teenager and in an institution, he had a “teenager temper tantrum, and I was just out of control.”

“I remember a guy by the name of Bruce. He grabbed me, because I was out of control. He just grabbed me, put his arms around me and just held me, and I was trying to get away and all of those things, he just didn’t let me go,” the man said. “He didn’t allow me to hit him or none of the above. Ultimately, I just tired myself out, and I just cried.”

Bruce didn’t hurt him.

“He didn’t disrespect me. He didn’t belittle me. He allowed me to calm down, and then he started to talk to me. And I say that because to this day that was an act of love. And it was not an act of disrespect,” the man said. “And so I think when it comes from the family and from the community, it’s a better perspective versus it coming from the police, because police can’t do just that — they’re gonna police.”

This technology can be used for specific tasks as well. After Madison, Wisconsin, police officers shot a Black man named Tony Robinson and the police chief suddenly retired, the Madison Police and Fire Commission asked Roy’s group to help the department listen to the community and use the people’s voices and concerns to craft questions, and do so in a transparent, trusted way.

He said his group worked closely with local community members to engage with marginalized communities and people who do not routinely show up to town hall meetings. He said town hall meetings can be sometimes performative, especially given the three-minute speaking limit and the requirement to speak in front of a large crowd, and that smaller, group conversations are often effective in welcoming new voices.

“We heard a very different kind of perspective, (from) people who would not show up (to town hall meetings), or even if they did, would not share in the way that they did through these smaller conversations,” Roy said. “They knew they were being recorded. They were actually wanting their voice to create a durable record that was transparent and accountable.”

Roy’s group pored through the audio, with the help of artificial intelligence, and sorted recordings into different themes. Here are some of the voices that shaped the questions to the Madison police chief candidates:

“It’s hard to get away from how powerful the institution and the badge and having a gun is and how much that emboldens individuals,” said Carla, whose quote was sorted into the fear theme.

“Growing up, one of the first values and principles that I was taught was to never trust police in any situation or the circumstance. That was kind of proven to me around age 12 and 13, when I saw a family member be shot in the back eight times,” said James, whose quote was sorted into the trust theme.

“They are police and they police. That’s what they do. They’re not counselors, they’re not social workers, and so all of those factors (are) not even in the equation,” said Felix, whose quote was sorted into the scope theme.

“The police in this community and the communities across our country don’t look at people who need support, and people who need someone to guide them, or just be there for them through their struggles — they see them as a problem. They’re not a problem. They are people,” said Kimberly, whose quote was sorted into the disabilities theme.

These quotes were then used to help craft questions during public interviews. Roy said the public had access to how they came up with these questions and could even listen to the full conversations they sprouted from.

Currently, Roy’s group is assisting in the mayoral race of Boston, a historically segregated city, in a similar way.

“I hope you will also consider this simply as a case study of how some of the same technologies, where we see some of the problems in social media, can actually be leveraged to create new possibilities,” Roy said.

Matt Ewalt, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, ended the lecture by asking Roy one question: How can people get involved in this work?

Roy said they are looking for more communities to get involved in, particularly ones that have “experience or the capacity to facilitate conversation and dialogue.”

“We would love to hear from you,” Roy said, “because we are really set up to provide training and support and try to grow these kinds of efforts.”