Lillian-Yvonne Bertram kicked off the 2022 Chautauqua Writers’ Festival Wednesday, June 22, by reciting a simple dictionary definition to their audience: “Resilience,” Bertram said, “is the power or ability of a material to return to its original form, position, etc., after being bent, compressed or stretched.”

“Writing Resilience,” the festival theme, encapsulates the difficulties and dysfunction of the last two years, Bertram said.

“While we had to live with the fear of the early days of the pandemic, some of us experienced this in relative comfort and privilege, while others became the target of zealous demagoguery, such as anti-Asian violence and anti-Black violence,” they said. “Personally, I’m not sure how resilient I’ve been.”

For some people, writing through the pandemic was crucial, and the only way to process what was happening to their friends, family and loved ones, Betram said.

“For others, writing was impossible — there was no time, no space, no energy,” they said. “Our resilience, then, is still in progress as we strategize to survive every day.”

The past few days, for the first time since 2019, an in-person Writers’ Festival convened on the grounds. Bertram, the festival director, and Sony Ton-Aime, Michael I. Rudell Director of Literary Arts, kicked off the week with a welcome to attendees Wednesday in the lobby of the Athenaeum Hotel.

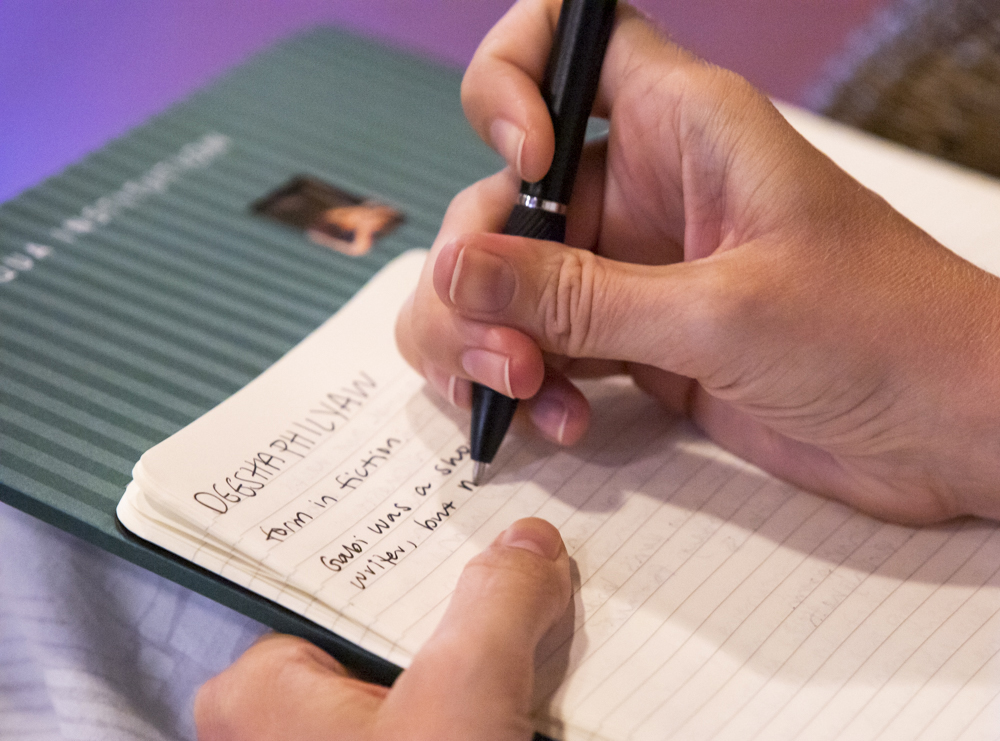

While the events of panels, workshops and readings conclude Saturday, the festival reached its zenith with a keynote Thursday in the Hall of Philosophy from 2021 PEN/Faulkner award-winning author Deesha Philyaw, a 2022 festival faculty member.

“I’m going to be honest with you: I chafe a little bit at the word ‘resilience,’ ” Philyaw told her audience.

Though she understands how resilience is often essential for overcoming adversity — like when Philyaw initially struggled to publish her collection of short stories, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, which went on to win the Story Prize, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and was a finalist for the National Book Award — Philyaw said that, in her mind, when people mention the word “resilience,” what they actually mean is “endurance.”

“I think about how, in the larger culture, we talk about the resilience of, say, children,” she said. “But we don’t talk as much about how many of us, as children, were far more resilient than we ever should have had to be growing up.”

Philyaw said she wanted people to keep sight of the fact that “someone, some institution or some system, or all three at once, are complicit in this harm, injustice, oppression or terror.”

She said that resilience is not necessitated without outside influence.

“People are not resilient in a vacuum,” she said. “I know that’s the feel-good story about resilience, but that’s not the true story; that’s not the whole story.”

True stories often make us uncomfortable, Philyaw said, and sitting with that discomfort can also require resilience.

Philyaw encouraged the audience to write and speak in an active voice when it comes to resiliency. She pointed out that passive voice can actually be exonerative.

“More specifically, as writers, I want us to consider those times when what those so-called resilient people have had to endure is us and our writing,” she said. “I want to invite you to consider different perspectives today on resilience.”

It’s possible for us to be both “the oppressed and the oppressor,” Philyaw said, as well as “the harmed and those committing the harm.”

“I believe being a good literary citizen requires us to consider the harm we might do, even unintentionally,” she said. “It requires our resilience. What’s best for us might be to reconsider, or even start over. Our stories, and who tells them, matter.”