Column by Mary Lee Talbot

“I sing African American spirituals a lot. They came out of a history of pain and I am fascinated by their beauty, their mystery and how subversive they are,” said the Very Rev. Samuel G. Candler. He preached at the 9:15 a.m. Monday morning worship service in the Amphitheater.

The title of his sermon was “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham,” and the scripture text was Luke 16:19-31.

Candler began the sermon by singing the chorus of the song. “Rocka my soul in the bosom of Abraham/ Rocka my soul in the bosom of Abraham/ Rocka my soul in the bosom of Abraham/ Oh rocka my soul.”

Many of the African American spirituals were sung in opposition to “the white man, the rich man,” Candler said. “A lot of us here are white, rich folks but we don’t like to recognize or admit it. We always point to someone else and say, ‘I am not as well off as they are.’ But we are here and we are better off compared to others in the world.”

In setting the context of the story, Candler told the congregation that “we want to identify with the hero, the person who is blessed in Jesus’ stories. This one does not favor the rich guy.”

In the story of Lazarus and the rich guy, the rich guy is not named; it is only later he is called Dives. “We know the name of the other guy who is sickly, poor and hungry — he is named Lazarus. The rich guy is ignored.”

When they died, Lazarus went to the bosom of Abraham and the rich guy went to a place of torment. This is not a story about who ends up where, said Candler — “it is about who is listening to whom, it is about relationship, it is about righteousness as holy relationship.”

The rich guy asked Abraham to send someone to help him or his brothers. He wants Abraham to send Lazarus. Abraham tells the rich guy, “If they won’t listen to Moses and the prophets they won’t listen.” The rich guy asks, “What if someone comes back from the dead?” Abraham tells him no, his brothers would not believe.

Candler said that often, this story is interpreted as talking about Jesus coming back from the dead.

“As you know, the answer to every Vacation Bible School question is Jesus.” The congregation laughed. “I can see you attended Vacation Bible School.”

He continued, “But what if the story is not about Jesus? There is another person who came back from the dead: Lazarus, the brother of Mary and Martha.”

“Rocka my soul” is about right relationships, good relationships. A right relationship equals a good relationship that identifies with the poor, the sickly and the outcast.

“African American spirituals are about the poor and oppressed,” Candler said. “They don’t identify with rich, white guys — if there were any white people in the Bible.”

As an example, he talked about the spiritual “Kumbaya,” which has come to represent a naive, oblivious faith. However, it is actually a very subversive song. Candler said its roots can be traced to the 1920s Gullah community in South Carolina and Georgia. “Someone’s crying, Lord, Kumbaya, come by here.”

The rich guy was afraid to touch Lazarus in life; he was afraid to “come by here.” But in Hades he wanted Lazarus to dip his finger in cool water and touch him, and if Lazarus could not do that, to go and speak to the rich guy’s brothers.

“What do we do with the rich guy?” Candler asked the congregation. “There is a chasm that you can’t get over. Fundamentalists say this story proves that Hades is eternal. But that is not the point. The point is to listen to love, to touch, to be in relationship with Lazarus.”

The second part of the song is, “So high, you can’t get over it, so deep you can’t get under it, so wide, you can’t get around it, you must go in at the door.”

The only way to get across the chasm is through the grace of God.

“There is something higher, deeper and wider than the chasm — it is grace that crosses chasms,” Candler said. “The bosom of Abraham is where the love of God prevails.”

Candler asked the congregation to listen to the poor guy who is now singing “Rocka my soul in the bosom of Abraham.”

“That is where all the children of God lie,” he said. “Abraham believed God, he was in relationship with God and it was reckoned to him to be in a holy relationship.”

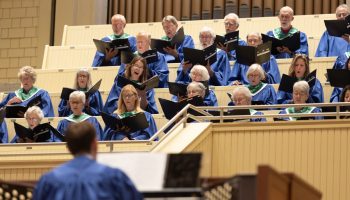

The Rt. Rev. Eugene Taylor Sutton, senior pastor for Chautauqua Institution, presided. The Rev. Luke Fodor, rector of St, Luke’s Episcopal Church in Jamestown, New York, read the scripture. The prelude played by Nicholas Stigall, organ scholar, was “In paradisum,” by Henri Mulet. The anthem, sung by the Motet Choir, was “In paradisum,” from Requiem, by Gabriel Fauré. The choir was directed by Joshua Stafford, director of sacred music and Jared Jacobsen Chair for the Organist, and accompanied by Stigall on the Massey Memorial Organ. The postlude, played by Stigall, was “Tu es Petra,” by Henri Mulet. Support for this week’s chaplaincy and preaching is provided by the Samuel M. and Mary E. Hazlett Memorial Fund.