Alton Northup

Staff writer

Paul M. Romer has an agenda.

“We have to make room for people to move into cities, and we have to do that even in the United States where it’s gotten too expensive for many people to move into a city to live and work,” he said. “But we especially have to do it with the developing world, where there’s so many people who still want to move into cities and who can’t.”

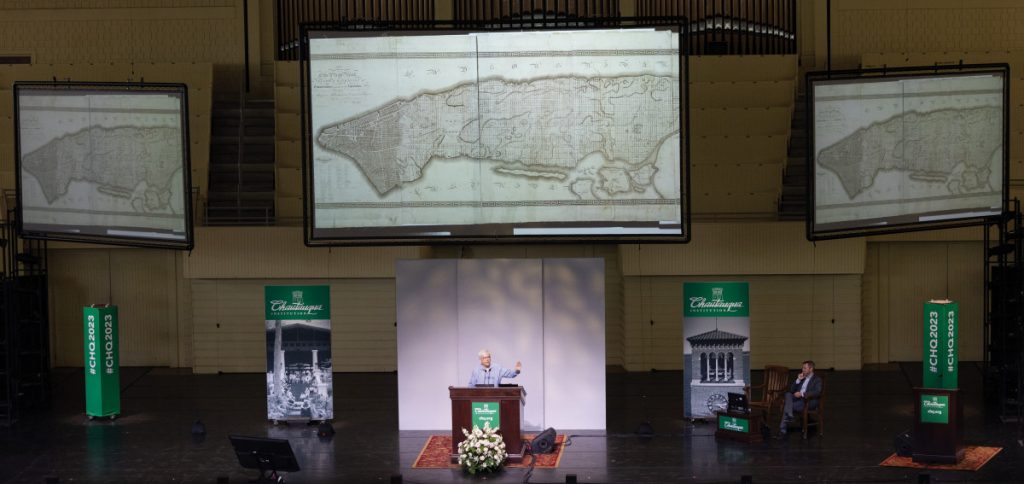

Romer, the Winner of the 2018 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, a professor at New York University and the former chief economist of the World Bank, said urbanization is central to a thriving society. He laid out how communities can urbanize in his lecture, “The Street Where I Live,” Monday in the Amphitheater to open the Chautauqua Lecture Series Week Five theme, “Infrastructure: Building and Maintaining the Physical, Social and Civic Underpinnings of Society.”

Romer’s understanding of infrastructure comes from New York City, where he moved because he wanted to understand its streets.

“Streets are one of the most important types of infrastructure,” he said. “Streets are the connecting mechanisms for us.”

In the early 19th century, outside of a clustered settlement on its southern tip, Manhattan was mostly farmland.

After several failed attempts from the Common Council of New York City to divide the land of Manhattan for development and sale, the New York State Legislature appointed a commission in 1807 with the sole power of surveying and planning the land.

The three-man commission consisted of Gouverneur Morris, John Rutherfurd and Simeon De Witt – though it might as well have been a one-man team with Morris driving its actions, Romer said.

Morris, writer of the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, decided the new developments should promote accessibility and inspire growth. The best way to achieve this, he settled, was through a grid plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid. In planning, surveyors planted spikes throughout the city to represent future intersections.

In March 1811, the commission presented an 8-foot map of Manhattan overlaid with the new streets and blocks. The design allowed for more than 1 million residents, an unheard of population in Colonial America, and throughout the next two centuries, its streets have accommodated railcars, automobiles and bikes – inventions that came decades after the map’s design.

“The beauty of this story is that the government had a significant amount of public space where it could make decisions about how to use it as the world evolved and changed,” Romer said.

While the commission worked with a nearly blank slate, several already-established properties forced adjustments to the design. St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery and the Stuyvesant Fish House, home of future New York Governor Hamilton Fish, stood directly in the planned lines of 9th and 10th streets.

Through compromise, a diagonal Stuyvesant Street was incorporated to preserve both the home and the church. This process of compromise and adjustment continued in the centuries that followed, Romer said.

A portion of the street between 10th Street and Second Avenue, directly in front of the church, is now Abe Lebewohl Park. In 1938, this plot was a sitting area called St. Mark’s Park, though it became dilapidated by the 1970s. Residents Marilyn Appleberg, Beth Flusser and Abe Lebewohl petitioned the city in 1980 to save the park after discovering it was under control of the city’s parks department.

“Within the frame of something like the commissioner’s plan for New York City and within the process of compromise where some owner of a house, like the Stuyvesant-Fish family, could influence what actually happened, there was room as well for citizens to express their voice,” Romer said.

He now wants to implement Manhattan’s process in the developing world through what he calls “The Making Room Agenda.”

By making a pre-established route for electric lines, sewer systems and public transport, he said the most expensive cost of infrastructure – the process of getting people to decide together – is removed from the equation. Urbanization, he said, promotes advancement of society as it creates access to jobs, education and collective thinking.

“If you try to provide a structure second, you make the challenge almost impossible,” he said.

While “economists have de-emphasized coming together,” Romer said they should talk more about what they can do to support collective work. Introducing the planned city concept to the developing world was central to his mission at the World Bank, and he has already seen success in its implementation. But just as New York City did not become a metropolis overnight, it may take decades for markets to invest in an urbanized developing world.

“It is hard and we should not get discouraged by the fact that it’s hard,” he said. “We should just keep in mind that the benefits from that kind of connection are so enormous that we must keep struggling to work together.”