Alton Northup

Staff Writer

Very few Chautauquans consider themselves gamers.

Colleen Macklin opened her lecture attempting to challenge that belief: After an initial hand count, roughly a dozen people self-identified with the label; but when she asked who started their morning with a round of “Wordle,” many more hands went up.

Still, Macklin, an associate professor of media design at the New School’s Parsons School of Design, had some work to do before persuading the crowd of their inner-gaming abilities.

She presented her lecture, “Gaming the System: What Games Can Teach Us About the World and Ourselves,” at 10:45 a.m. Monday in the Amphitheater to open the Chautauqua Lecture Series Week Two theme, “Games: A Celebration of Our Most Human Pastime.”

Macklin, the co-director of PETLab, which develops games based on social engagement and experimental learning, sees gaming as crucial to human development and understanding.

Children’s initial interactions with language as a form of play inspired Macklin to develop her game “Dear Reader,” which turns classic literature into word puzzles. When working with the Red Cross, she learned the native games of Ghana and modified them to teach Ghanaians how to stay prepared in climate change-affected areas.

In 2009, she even developed a new sport – Budgetball – that pits college students against congressional budget officers in a game of fiscal and physical competition. Many of her games could be considered educational tools. For Macklin, learning through play is human nature.

“I truly believe that being playful means thinking more deeply about the world, about each other and about our role in life,” she said.

Of course, she would not be able to make her point without including some gameplay in her lecture. So, she asked Chautauquans to join her in a game of “Five Fingers.”

The rules are simple:

Make a group of three to five people

Have each person hold up five fingers

Form a circle and take turns (going counterclockwise) pointing at someone

If you are pointed at, you lose a finger

The last player with a finger – any finger – wins

The game was an instant hit as Chautauquans gathered in groups, forming alliances or secretly conspiring against their family members – there were even accusations of a six-fingered cheater.

When the crowd settled, Macklin said there was more to the game than its entertainment value. There were lessons on society and games that could be learned by playing “Five Fingers.”

“Games make rules fun,” she said. “That’s one of the most interesting things about games; they take things in the world that normally aren’t fun and turn them into fun.”

She said children, starting at age 5, develop an obsession with rules and start to make their own games at recess. This creative outlet gives children a safe environment to learn to follow rules – and what happens when they are broken.

“We don’t fully understand something until we see it fail,” she said. “A game teaches us that lesson.”

People typically avoid risks due to the possibility of failure, but those inhibitions go away in a playful setting. Macklin used an analogy of a kitten: If the real world is a lion, strong of claw and sharp of teeth, then games are cute, fluffy kittens in a bowl of marshmallows.

For thousands of years, she said, games have served as crash courses on society. One of the first games she developed was an Electoral College simulator and it gave her college art students a clearer understanding of the United States’ political system.

Because games shrink society into something tangible, “we can take our world and understand it more deeply through games,” she said.

Through collaboration and competition, games also help us understand each other better, whether it is your Aunt Sally’s need for revenge or how to work on a team.

And, despite popular belief, games teach us that the rules can be changed – just as long as you are not the only one who knows. As a game designer, each game Macklin works on goes through dozens of rule changes before it hits the market.

“That’s why game designers do something that’s called play testing,” she said. “We have to see how the game is played before we can even understand what it is that we designed in the first place.”

All of us, she said, are game designers who can change the rules that are not working in our lives.

“I hope that we can all stay game designers, too,” she said. “It’s really important to be consistently asking oneself ‘What are these rules that I’m living by and how do I redesign them to make life more fun or rewarding?’ ”

Because of the responsibility games give to players to follow the set rules, Macklin said games teach us that simple rules can create great complexity, even a game as simple as “Five Fingers.”

Much like the societies they come from, games are systems; a set of elements interconnected with a purpose. And while “games let us play with little systemic reflections of the world,” she said, the real systems are not designed to be as understandable. Games make system dynamics understandable through play.

Macklin highlighted free online games, such as “Explorable Explanations” by Nicky Case, that can teach the concepts of new voting systems, how to tune a guitar or the basics of probability and statistics. In David O’Reilly’s “Everything,” players can see from the perspective of an atom, design their own universe or let the game play itself.

As our world increasingly mirrors the worlds created by games with the advent of artificial intelligence (appropriately, it was at this moment Macklin’s Siri decided to respond to a prompt in her lecture), and apps have replaced traditional methods of grocery shopping, socializing and even dating, games can help us imagine new possibilities.

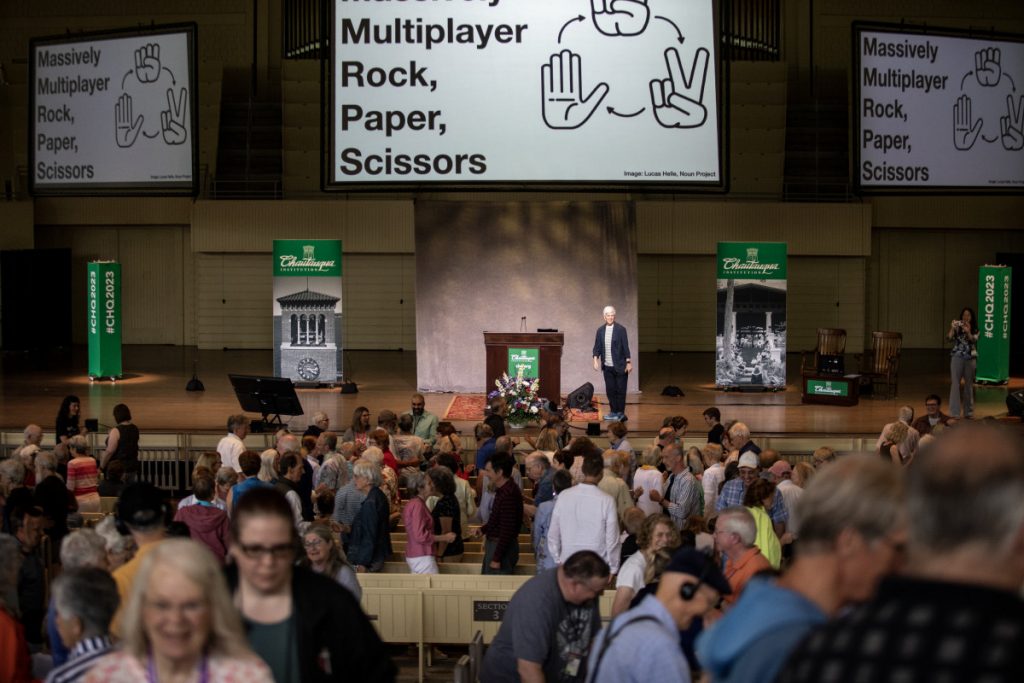

To end her lecture, Macklin held an old-fashioned game of Rock, Paper, Scissors. Though with more than 2,500 people in the Amp, she dubbed it “Massively Multiplayer Rock, Paper, Scissors.”

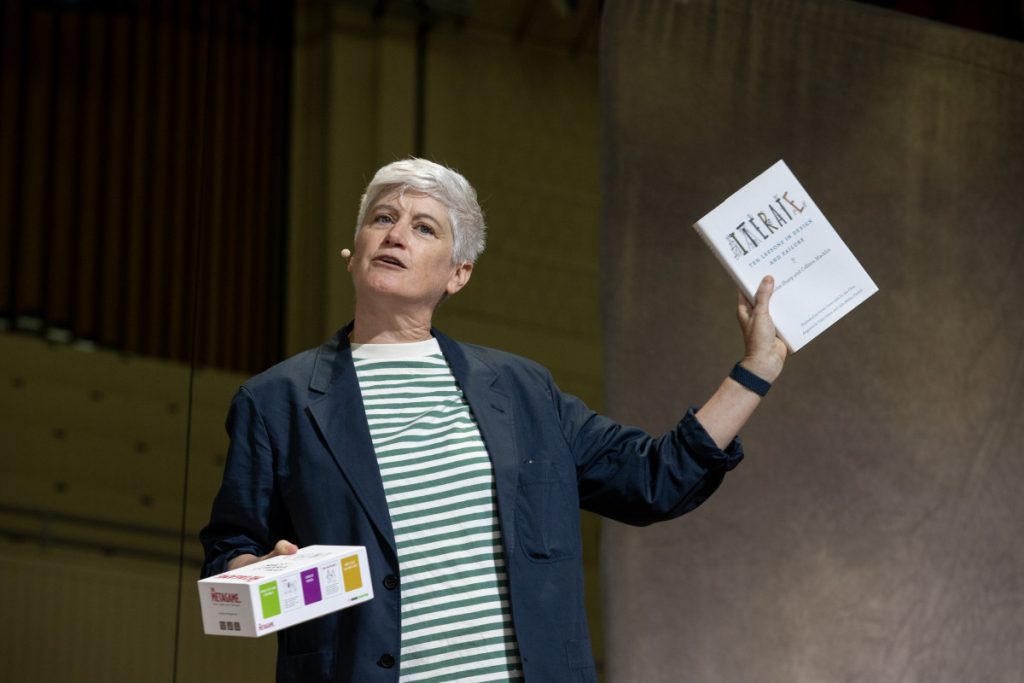

After nearly 10 rounds the competition was narrowed down to Chautauquans Dan and Kathleen, who faced off in a best-of-three round for bragging rights and a signed copy of Macklin’s latest card game, “The Metagame.”

The first duel was Dan’s for the taking, but Kathleen got points on the board in the second round as Dan failed to brush off the crowd’s heckling. The tie-breaking third duel resulted in a suspense-building tie. Then, the fourth duel resulted in another tie — which Macklin insisted was not planned.

As the crowd sat on the edge of their seats, Kathleen swooped in for the win.

She earned the well-deserved title of Massively Multiplayer Rock, Paper, Scissors champion.