Sara Toth

Editor

Any teacher knows that play is an important tool in the toolkit of education — even, or especially, in religious education.

When Christian theologian Jerome Berryman taught Rabbi Michael Shire a new way of playing, Shire knew he had to introduce a new methodology in the teaching of Jewish religious education.

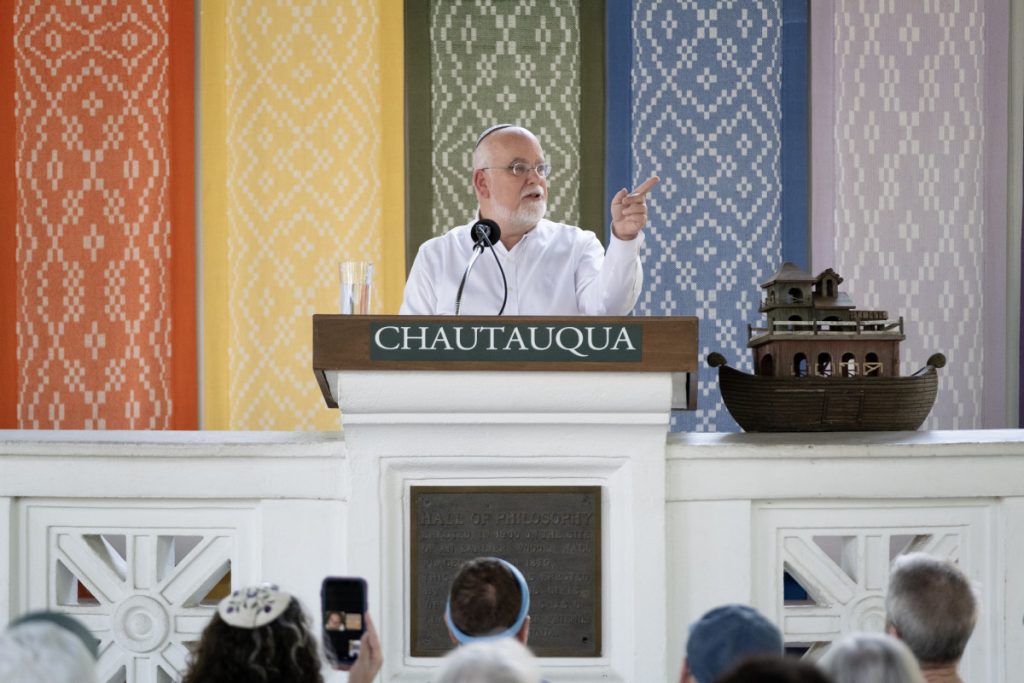

“Godly Play is a method of playing with sacred story from our faith traditions. That’s the heart of faith formation and spiritual developments,” Shire said to open his presentation as part of the Interfaith Lecture Series Wednesday in the Hall of Philosophy, speaking to the theme of “A Spirit of Play.” “…. (Torah Godly Play is a way to) enhance the spiritual development of children and adults through the telling, and the exploration, of sacred story.”

Shire, who is the academic director of Hebrew College’s Master of Jewish Education program, outlined Torah Godly Play as an approach centered on storytelling, combined with “natural artifacts carefully and intentionally included for spiritual resonance” — sand, wood, stone, clay. As an example, he brought with him a model of Noah’s Ark, perched on the podium alongside him.

Centering stories and playfulness allows for a “time of wandering and a creative exploration,” he said. “This encourages the heightened consciousness and enables the learner to make these sacred stories their own.”

It’s not about telling stories of faith to learn them, but to find meaning within, and hear the spiritual call of, those stories.

“Stories are a natural way to hear God’s call,” he said. “Playing with those stories is an inherently Jewish way to understand and respond. Drawing upon the Hebrew Bible, the Torah Godly Play invites children into the narrative while leaving room for wonder, creativity and imagination, as they build their own religious language, to express the curiosity as well as the conceptions of a divine presence in their lives.”

Play, Maria Montessori once said, is children’s work. But it’s not restricted to just children, Shire cautioned — play should be the work on anyone who is curious, at any age. Judaism, in particular, has a “lively and interpretive tradition of actively interacting with its holy texts. … Judaism loves playing with our texts, and using this play to discern their hidden meanings.”

Playfulness — long a part of religion, with its “make-believe and fancy dress” — is an expression of freedom, of agency, Shire said. Most importantly, play is conducted for its own sake. Rules are structured by the players themselves, and can be changed by those same players.

“This is very much how Judaism has structured its literary tradition and the work over centuries to play with the language of sacred text,” he said. “… Being curious about the way the world works, and its implications for making meaning is a key ingredient of Jewish life. But in order not to get too speculative, we keep ourselves grounded in the real world.”

For that grounding, Shire shared three ways Judaism uses both the questioning of and playing with stories to find spiritual depth.

The first is through the literary device of the Midrash — “an interpretive and often playful commentary on the Torah. It fills in gaps in the text or extrapolates meaning to extend the biblical characters motivations.”

The second, Shire said, is “language play,” which encourages close readings of the text to glean implicit meanings. The first time that play is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible is when Isaac plays with his half-brother, Ishmael. Isaac’s mother Sarah views the children’s play as inappropriate — Ishmael is, after all, Hagar’s son. Sarah becomes cruel; her husband Abraham obeys; Hagar and Ishmael are banished.

“But then comes rescue from divine protection in the form of a well of water, and a promise that Ishmael will father a great people — but a separate people from Abraham, from Isaac,” Shire said. “The very story is a play on itself,” as Yitzchak, Shire reminded his audience, means laughter. Isaac’s name means to laugh.

“These children are playing. Yitzchak, laughter, and Ishmael, man of God, they just want to play together,” Shire said. “But the tragic circumstances of their parents, of history, … separate them and their legacies. The interactions between Isaac and Ishmael from then on — to this very day — results in division and conflict rather than play and laughter.”

The third way Judaism questions and plays with sacred story, Shire said, is through religious liturgy “that endeavors to lighten the darkness of Jewish history and religious persecution.” That endeavor is particularly pronounced in the festival of Purim, a “festival of merriments” celebrating the victory of Esther and Mordecai over Haman — an Achaemenid official intent on annihilating the Jewish people.

“The first recorded instance of anti-semitism is turned into a raucous play much to the merriment of young children,” Shire said.

Grown-ups know the darker side of these celebrations; but as children dressed as Cossacks celebrate alongside adults wearing visible signifiers of their Orthodox Jewish faith, Shire asked, “What could demonstrate the power of play more poignantly than dressing up as the very enemy who wanted to kill you?”

The “wonderful and joyous playing with sacred text,wrestling with God’s meaning for us, seeking to understand that our lack of control in our own lives, or the reasons for our pain and suffering, enables us to become authors of our own search for meaning,” Shire said.

It gives license to a range of reactions to both the good and bad in life, and play — structured but not necessarily goal-oriented, is “ideal for this kind of spiritual knowing,” Shire said. “It is available and accessible from the youngest learner to the very oldest and it is the foundation upon which to build self awareness and self awareness for ourselves and awareness for others on a lifelong journey of playful growth.”

For children, play comes naturally. Their innate curiosity and imagination, guided by Godly Play, lets them “author their own orientation to biblical story, side by side with trusted adults who wonder with the children together,” Shire said. He concluded by asking his audience to continue to enjoy the spirit of play embedded in our religious faiths, … in our stories, in our fanciful legends, in our texts, and our interpretations of them.”

In doing so, “we can pass on the vitality, the solace, the joy, the memory, the critical voice, and the spiritual sustenance that gives life to religious experience and faith.”