Alton Northup

Staff Writer

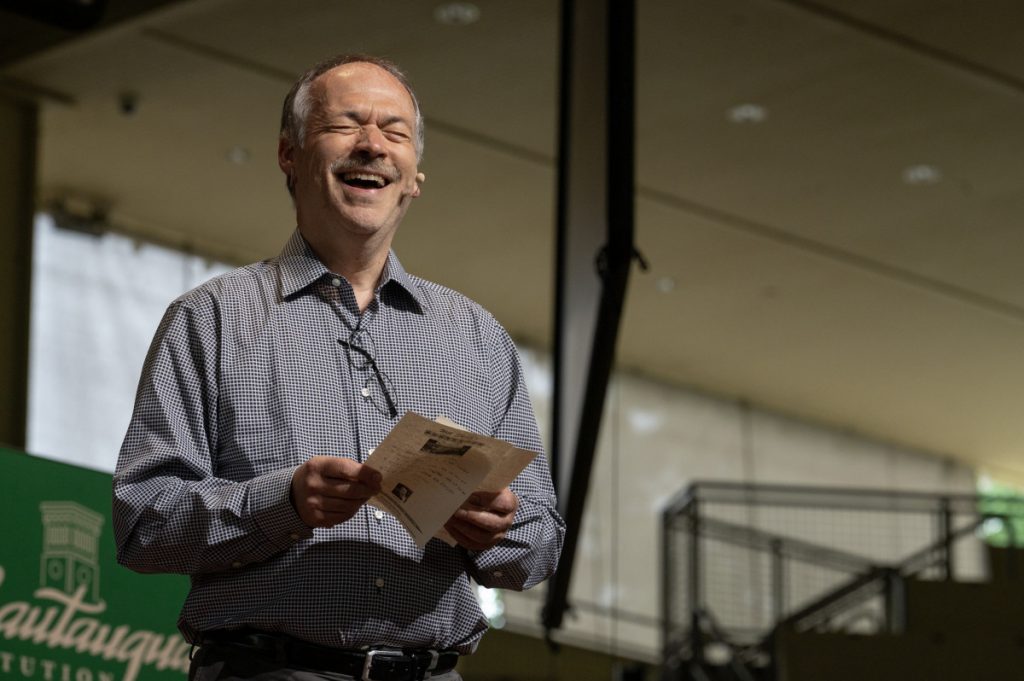

In the 8th grade, when asked to write a paper on what he wanted to do in life, Will Shortz chose professional puzzle-making. And while the career choice puzzled his teachers and classmates, for Shortz, the clues were always there.

“I wrote that it would be a life of ease,” he said. “I would just sit back and make my little puzzles.”

Shortz, who sold his first professional puzzle at 14 years old, is celebrating 30 years as the The New York Times crossword editor this year. He shared his love of crosswords and the history of the puzzles at 10:45 a.m. Friday in the Amphitheater to close the Chautauqua Lecture Series Week Two theme, “Games: A Celebration of Our Most Human Pastime.”

Shortz ended up with a B+ on that essay and decided to explore other career options during high school, including disc jockey and mathematician. Despite the lack of degree programs for puzzle-making, every path he took led him back to his childhood dream.

Luckily, his mother discovered Indiana University’s individualized major program. He developed his own course work consisting of 20th-century American puzzles, crossword construction and the psychology of puzzles. His 100-page thesis was on the history of American word puzzles before 1860.

“This had been my dream … and now I found I could do it,” he said.

Upon graduation, Shortz became the first, and only, person to hold a college degree in enigmatology, or the study of puzzles.

The history of crosswords is another of Shortz’s obsessions. He owns the largest collection of puzzle paraphernalia in the world, including pieces dating back to 1545. But the modern crossword dates back 110 years.

Arthur Wynne, an editor for the New York World, introduced what he called a “Word-Cross Puzzle” in the Dec. 21, 1913, Sunday “Fun” section.

By the third week, Wynne changed the name to crossword. As they became a weekly fixture of the paper, the puzzles developed a “crank,” or eccentric, following.

In 1924, two Columbia University graduates, Richard Simon and Max Schuster, were looking for books to publish. Following a suggestion from a relative, the two approached the New York World puzzle editors and walked away with 75 unpublished puzzles.

Simon and Schuster published the collection of puzzles in April of that year; the first printing of 3,500 copies sold out. By the end of the year, the publishers’ three crossword books ranked No. 1, 2 and 3 on the national non-fiction bestseller list.

Shortz now owns the very first copy of that crossword book, which includes an inscription by Simon and Schuster thanking Simon’s father for his investment in their firm. The inscription ends saying they are “ushering in the crossword puzzle era” together.

“Everybody was talking about crosswords in the 1920s,” Shortz said.

As publications started pumping the puzzles out, one big player abstained – The New York Times. The ’20s were full of crazes, Shortz said, and the publication saw crosswords as no more than a fad.

“The Times thought crosswords were beneath them; they didn’t do cartoons,” he said. “They actually ran an editorial decrying the popularity of crosswords, saying they were a childish pastime.”

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, an editor for the paper conceded that the puzzle deserved a spot in the paper as a distraction from the hard news of the war. The first crossword in the Times ran on Sunday, Feb. 15, 1942.

“One of the reasons we do puzzles is to put the world in order,” Shortz said. “Most of life’s problems don’t have solutions; we just muddle through and do the best we can. With a crossword, there is one perfect solution.”

The paper hired Margaret Farrar, who was co-editor of the original Simon and Schuster puzzle books, as editor. From the start, Shortz said, the Times set a new standard of quality for crosswords.

Making a crossword is simple: The diagram must be symmetrical and every square has to be a cross answer or a down answer. Two-letter words and repeat words are not allowed and the words need to be real.

What makes a good crossword, Shortz said, is having a good vocabulary full of interesting phrases. Lively clues also keep a puzzle fresh and entertaining for readers.

Though some of his favorite crosswords, he admits, are the ones that break the rules. In 1996, the Times ran an election day crossword where the clue was the winner of the election; both candidates’ last names worked as the answer.

President Bill Clinton was an avid crossword player; he told Shortz he played as many as three puzzles per day while on the campaign trail. During a timed session with the editor, in the middle of which Clinton answered a phone call, the former president solved a crossword in just 6 minutes and 54 seconds.

For the past 110 years, people of all ages and backgrounds, even the president, have started their day the exact same way.

“We live in an age now where more people than ever use their brains to make a living,” Shortz said. “… If you’re using your brain all day to work, when you’re done, you want to use your brain to play.”