Column by Mary Lee Talbot

“Theodore Roosevelt, TR, governor of New York, president of the United States, imperialist, social Darwinist, conservationist, called Chautauqua ‘the most American place in America,’ ” said the Rev. William Lamar IV. “So as Jesus asked people who sought out John the Baptist, what did you come to see? What did you come to Chautauqua to see?”

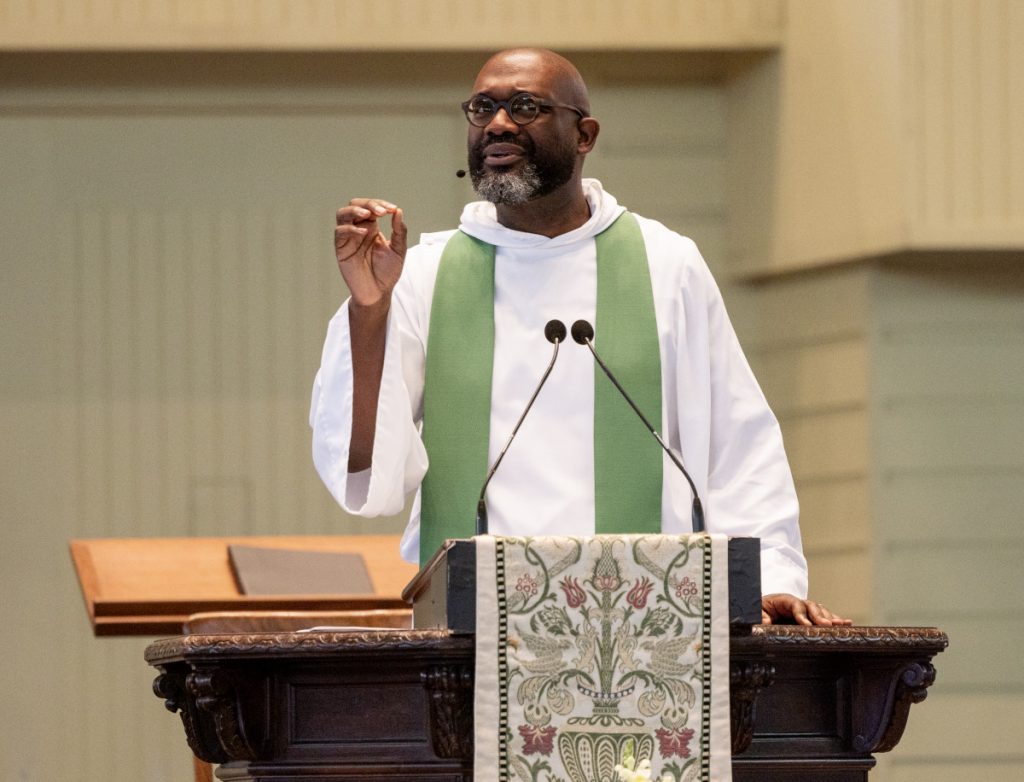

Lamar preached at the 10:45 a.m. Sunday morning service of worship in the Amphitheater. His sermon title was “An Open Door,” and the scripture reading was Revelation 4:1-8.

Many people come to Chautauqua to see preachers, show-business types — sometimes one and the same, he said in an aside — teachers, musicians and scholars. “We are worshiping in the birth suite of a movement,” he said. “Circuit chautauquas brought light and levity to communities and plunged them into knowledge.”

He continued, “Here in Chautauqua, the beauty is natural, the houses are stately, the parks verdant. Your kind of people, my kind of people, our kind of people are here. It is exclusive and expensive and intellectually and politically broad. Where else would you have Karl Rove and David Axelrod on the same platform?”

Lamar told the congregation he came to Chautauqua because Melissa Spas, vice president for religion at Chautauqua, asked him. He has enough ego to want to be on the roster with the other great preachers who have been here and he was curious about “what goes down here.”

“I want to juxtapose what you hear – lectures, worship, laughter, the bell tower that clandestinely reminds you your life is ticking away every quarter hour, a saxophone at dusk – with what I hear: the sound of the blues,” he said. “I hear the sound of the potlikker, cornbread blues, the ‘Hellhound on my Trail,’ blues written by Robert Johnson in 1937.”

Lamar called “Hellhound” the apogee of the blues. He quoted the lyrics: “Blues fallin’ down like hail, blues fallin’ down like hail, blues fallin’ down like hail, blues fallin’ down like hail … there’s a hellhound on my trail, hellhound on my trail, hellhound on my trail.”

In the midst of the beauty of Chautauqua, hellhounds are on the trail, Lamar told the congregation. “You may not see them, but they are here and they even know the addresses of Chautauquans.”

The Book of Revelation has long had its critics. St. Jerome said the book has as many mysteries as it has verses. Author D. H. Lawrence called it the most detestable book in the Bible. Martin Luther, the German reformer, said it was not apostolic or prophetic and should not have been included in the Bible. Thomas Jefferson called the book the ravings of a maniac.

“I say to them, they are all wrong. As my grandmother said, as wrong as two left shoes. Those who put the book in the canon, who saw the cinematic vision, were right. It must be preached,” Lamar said.

God revealed the vision to Jesus Christ and Jesus revealed it to John, often called John the Revelator. Lamar said, “St. Jerome, Lawrence, Luther and Jefferson could not see or hear the hellhounds, but John was in prison and the hellhounds were just outside his cell.” John had said no to the politics, religion and economics of his time. He was not in prison because he had committed a crime, but because he would not be a chaplain to the status quo.

“He was searching for the divine presence in perilous times,” Lamar said. “The church was blending with the civil order, with the cult of the emperor. As Christians assimilated, it was hard to tell who was a follower of the Crucified Jesus and who was not. Sounds like today.”

He continued, “Some Christians who refused to be in the culture were considered suspicious by people who fell in line with the culture. I wish more people were suspicious, of us today. They are not suspicious, but use us as cover to do things that fly in the face of Christ.”

John looked to heaven while the hellhounds were barking. Lamar said it takes faith, imagination and courage to look in the midst of challenges. John looked and saw a door open in heaven. “He looked and God lifts up those who will look. Our American world is designed for us not to look up, to see something more grand, to see the door in heaven.”

One of the challenges of modern faith is that people no longer believe in history or mission. “We miss the wind of the Spirit. John looked and there is an invitation for all of us to look into the mystery between time and eternity, kairos and chronos, the throne of ego and the throne of God,” Lamar said.

When he was in seminary, Lamar did not understand what good it was to tell this story of the mystery, imagination and vision found in Revelation. As he has grown in wisdom, he sees the Book of Revelation as an invitation to participation in God’s glory, not escapism.

“We can participate in the glory of God in time and space. In this place, in this nation, there is an open door to see God’s glory and majesty, to live in beauty and justice in a world that makes us more beautiful in our daily lives,” Lamar said.

Even at Chautauqua, the hellhounds are barking the blues among us, he said. “The hellhounds of facism are loose in the United States, Europe and Africa. Need I remind you that the hellhounds of climate change are burning away. The hellhounds are here.” Then a dog barked at the perimeter of the Amp.

John the Revelator left hope. Even though he was in a cell, he saw a vision of God “so beautiful it has the possibility to change us all,” Lamar said. “I hear the hellhounds but above I hear the music; there is a God somewhere. Can I get the dog to bark?”

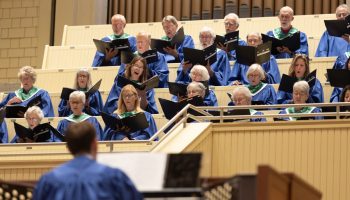

The Rt. Rev. Eugene Taylor Sutton, senior pastor for Chautauqua Institution, presided. Alison Marthinsen, a sixth-generation Chautauquan and a member of the Chautauqua Choir, read the scripture. The prelude was “Carillon, Op. 31, No. 21,” by Louis Vierne, played by Joshua Stafford, director of sacred music and Jared Jacobsen Chair for the Organist, on the Massey Memorial Organ. The Chautauqua Choir, under the direction of Stafford and accompanied by Nicholas Stigall, organ scholar, sang “Let the world in every corner sing,” music by Ralph Vaughan Williams and text by George Herbert. The prayers of the people came from the Hip Hop Prayer Book, edited by the Rev. Timothy Holder, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip-hop on Aug. 11, 1973. The offertory anthem, sung by the Chautauqua Choir under the direction of Stafford and accompanied by Stigal, was “Bring us, O Lord God, at our last awakening,” music by Paul Halley and text by John Donne and Isaac Watts. The postlude, played by Stafford, was “Toccata in B Flat Minor, Op. 53, No.6,” by Louis Vierne. Support for this week’s chaplaincy and preaching is provided by the Alison and Craig Marthinsen Endowment for the Department of Religion.