Concluding Week Seven’s lecture series with Kwame Alexander, actor, composer, and songwriter Christopher Jackson, who originated the role of George Washington in Hamilton, took to the stage.

“(Have) you ever been to the grocery store, and people come up to you, and they say, ‘Alexander Hamilton, there are a million things I haven’t done’? Does that happen?” said Alexander.

“Never,” joked Jackson.

At 10:45 a.m. Friday in the Amphitheater, Jackson and Alexander ended Week Seven’s Chautauqua Lecture Series theme, “Kwame Alexander and Friends: The Power of One” by discussing Jackson’s background, his role in Hamilton and creating an impact in the world.

Jackson began acting on Broadway in 1997, as an ensemble cast member and understudy for Simba during the original Broadway run of The Lion King. Since then he’s appeared in Holler if Ya Hear Me, After Midnight, The Bronx Bombers, In the Heights, Memphis and Hamilton, which netted him a Tony nomination for Best Featured Actor in a Musical.

Alexander is a poet, educator, producer, No. 1 New York Times bestselling author and the Michael I. Rudell Artistic Director of Literary Arts at Chautauqua Institution. His works include The Crossover, which was recently announced to be adapted for the stage by Chautauqua Theater Company, with Jackson as part of the creative team.

Jackson hosted the Emmys in 2023, where he and Alexander first met, and where Alexander won for his Disney+ series “The Crossover” as a producer.

Alexander boasted his Emmy — which he had on-hand, ready to show off, one of many onstage surprises to come.

They opened up the conversation by discussing the role of music in our lives. Alexander asked if it has the power to “free us.”

“I never open my mouth and not try to free myself of something,” Jackson said. “I think we know enough about how the human condition works in our society, but I am still singing things that were oppressing my father’s father’s, father’s father.”

This realization came to him in part when performing, as George Washington, in 2016 at the White House in front of then President Barack Obama.

“Those words came to Lin-Manuel Miranda, who gave them to me, that I got to sing in the role of a man who would have held my great-, great-, great-, great-grandparents in bondage, in a song about the institution that not only has the capacity to allow that to happen, but also, the capacity to make the whole institution extinct,” Jackson said. “My grandmother never thought that I would be in the East Room singing as a president to the first Black president in our country’s history.”

While Jackson’s grandmother didn’t have that dream, he learned his first-ever song beside her at a piano. It helped his own understanding of the power of music and how it can free people.

Alexander referenced Africans being forcibly removed from their homes and how they used music as a means of communication.

“The music became the language,” he said. “What would that sound like?”

To answer, Jackson led the audience in a rhythmic hum. At the conclusion, he reflected on the meaning of the communal exercise.

“Those are the notes to tell the story for you. The longer that you do that, the longer you allow yourself to sit, it becomes a meditation,” Jackson said. “… In any particular moment, because you have already given us the imagery of the seed and a limitless sky, the evolution, it would have morphed into something completely different.”

Alexander steered the conversation about history toward Hamilton and Jackson’s critically acclaimed role as George Washington.

Jackson cited himself as one of two people to not audition for the musical — the other actor to not audition was Miranda, the show’s creator. Miranda brought the idea to Jackson while they were mid-performance of In the Heights on Broadway.

“It’s a concept album about the treasury secretary,” Jackson recalled Miranda telling him.

A few days later, the director of In The Heights began referring to him as “G.W.,” for George Washington — Jackson, at the time, had no idea what the director was talking about.

It was five more years before the show debuted. After he bought Ron Chernow’s Washington: A Life, Jackson’s life as Washington took off.

“I read that book seven-and-a-half times,” Jackson said. “I had a five-and-a-half year head start, so there were a lot of workshops in the development of the show. I am a history nerd anyway, so for me, that was my bible for the show.”

He recalled a lot of source material, specifically Hamilton’s own writings, as inspiration for his performance as Washington. After Alexander asked if there were any commonalities between the performer and the character, Jackson reflected on an unfortunate tragedy: Washington’s father, best friend and brother all died before he reached the age of 16.

“My father, who I had a difficult relationship with — to say the least — passed away at the end of the first week of previews,” Jackson said. “So, to be quite fair, for the Broadway run, that particular instance influenced me.”

The two discussed acting, and how actors making themselves vulnerable is part of the job.

“As an artist, it’s my job to put myself in the position to be uncomfortable in front of people. The choice to approach every day in humility,” Jackson said. “I get to stand on the Broadway stage again tomorrow afternoon at 2 p.m. I have no idea how well it is going to go, I do not know what my thought process is going to be, I am so excited for the opportunity to figure out what that is.”

He believes that collaborations are helpful for this humility and for strengthening art as a whole. To Jackson, it makes the experience more meaningful.

“I have never been on stage by myself or solely recorded a song or wrote a song that wasn’t influenced or directly impacted by someone, either literally or figuratively in the room with me,” Jackson said. “Collaboration is where the fun is.”

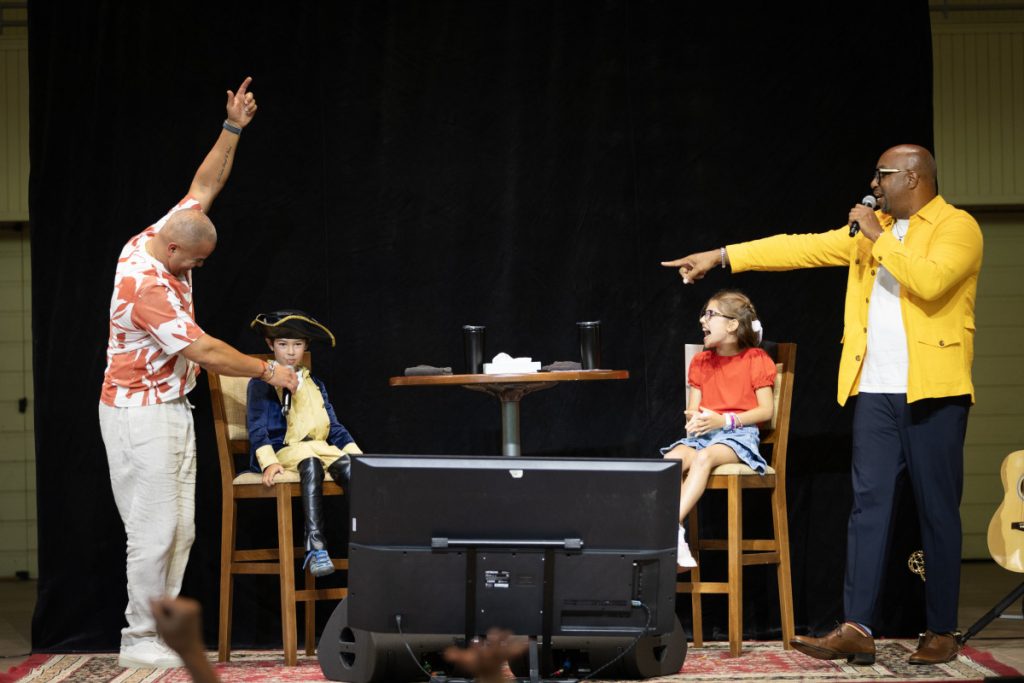

To emphasize the importance of joy and collaboration, Alexander brought two kids, Bella and Sully, onto the stage. Sully was dressed as George Washington and performed a snippet from the song “Aaron Burr, Sir.”

Bella asked about Jackson’s career and if he would change any of the decisions he made if he were 9 years old again, the same age as Bella.

“I would tell my 9-year-old self, ‘Don’t you dare stop taking piano lessons,’ ” Jackson said.

Sully asked Jackson about how he stays playful as a grown-up.

“Being a grown-up, it is hard to be reminded of how important play is,” Jackson said. “… I will make it my mission for the next seven days to do something that is so fun that I am not used to doing.”

After Bella and Sully returned backstage, Alexander explained his reasoning for their appearance.

“I realize that everything we do is to ensure that the people we love and who love us and who we leave behind have a much better life, or opportunity at life then we had. We want to create the kind of world where they can be connected and empathetic and be loved and be able to walk around and feel welcomed,” Alexander said. He asked Jackson if he had any place he would like to return to that elicits these feelings.

For Jackson, “St. Paul AME Church in Metropolis, Illinois,” is the place that elicits those feelings.

The church served family needs and operated as a cornerstone of his childhood. This was an important time in his discovery of music and eventually musical theater.

Alexander wondered if there was a single, most powerful moment he had experienced.

“Making an audience laugh, knowing that half of that audience has not laughed in a considerable amount of time,” Jackson said. “Knowing that either by a look, or a note, or a movement, I have been a vessel of expression.”

While it isn’t easy, it’s important that these expressions are seen. It allows for people to react to the performance emotionally, a theme Alexander used to end the lecture.

In his typical fashion, he had Jackson react to a piece of art he hadn’t heard before — this time, it was the still-unpublished Week Seven Chautauqua Community Poem.

“What I would like to do is read that poem and have you respond to it with a song,” Alexander requested.

He invited Sharon Roffman, concertmaster of the Chautauqua Symphony Orchestra, to play violin while he read for Jackson.

After the poem and while Jackson was reflecting on his impromptu song, Roffman discussed what she played.

“I was listening to the words you were saying and improvising what I think those words sound like,” Roffman said.

After deciding on the perfect song, the lecture concluded with Jackson’s performance of Bill Withers’ “Lovely Day.”

“You’ve made this a lovely day.”