Don Giovanni was given its premiere in 1787 in the Estates Theatre in Prague, a jewel-like house that in its present post- fire-code configuration seats fewer than 660. Naturally, Mozart’s grandly scaled score and da Ponte’s mind-expanding libretto can fill larger spaces, including the capacious Amphitheater, if measures are taken to adapt the musical and dramatic elements to the setting.

The Chautauqua Opera got it about half right on Saturday night. I mean this almost literally, as the second half fulfilled the potential of the first. After intermission, the mobile doorways that functioned as thresholds and objects around which to act were arranged with dramatic intent. Light and shadow were abundant, in keeping with the implications of the story. Modest as the production was — the only scenic properties other than the doorways were some chairs and a well-loved settee — it scanned as opera.

One interesting problem before the break was daylight. The arresting opening chords of the overture were hard to reconcile with the crepuscular end of a perfect summer day. Stage lighting was of no avail for the first 30 minutes. It did not help that those doorways were positioned at the edges, leaving a huge swath of stage to fill.

If Ned Canty’s direction was basic in the early going, singing made amends. Two experienced visiting artists, David Adam Moore and Richard Bernstein, quickly established themselves as convincing advocates of the title character and his servant Leporello, the former a slick baritone, the latter a rollicking bass, but close enough in sonority to make their role reversals believable.

Apart from gracefully carrying their tunes, they sustained the essential duality of this dramma giocoso. Horror and humour were maintained in a tense balance to the end. “He has a prior engagement,” Leporello quips when his master is on the brink of damnation at the hands of the spirit of the slain Commendatore. Shudder and laugh in equal measure: this is what Don Giovanni should make us do.

Arrayed against the licentious Don are three women of varying temperament. Alexandra Rodrick was a strikingly real Donna Elvira who communicated her volatility with vivid acting and a glint of steel in her mezzo-soprano voice. Rebekah Howell, a crisp-toned soprano, captured the mix of innocence and vacillation that characterizes Zerlina. It said something about the success of their portrayals that Elvira’s disruption of Don Giovanni’s planned conquest of the peasant girl elicited a round of applause.

Helen Hassinger, another Chautauqua Opera Young Artist, brought a bright tone and earnest acting style to the soprano role of Donna Anna, who sets the plot in motion by warding off an assault by the Don. It used to be popular to imply that the apparently resolute daughter of the Commendatore also is of two minds about her attacker. Perhaps this convention is no longer sustainable in the #MeToo era. Unfortunately, Canty found no other staging strategy for the scene, so the struggle, which is supposed to have a physical dimension, was purely vocal.

Strongest of the supporting gentlemen was bass Stephen Clark as Masetto. Tenor Dennis Shuman as Don Ottavio (who sang the Act 2 aria of the Prague version) and bass Brett Bode as the Commendatore struck me as a few years short of full possession of these roles.

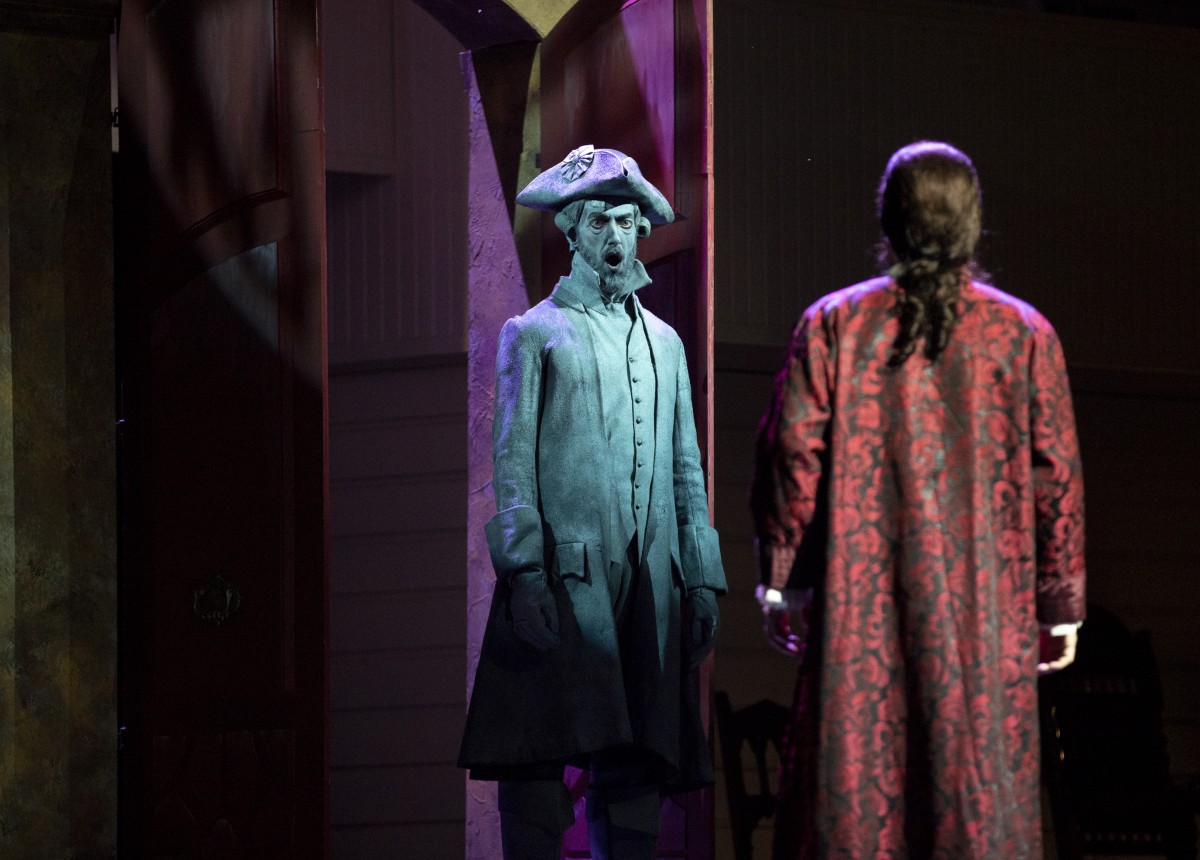

Canty kept the action simple, although there was some use of audience seating near the stage, notably for downstairs descent of Donna Elvira. The entry of the Commendatore near the end of the opera, always a coup de théâtre, worked well. The fearsome guest really looked like a statue come to life. The ushering of Don Giovanni into perdition by what appeared to be furies in bridal attire was so-so. We were expecting more.

Why a table could not be found for the Don’s aborted dinner engagement is a mystery. A few other questions suggested themselves. Why no mandolin for the serenade? Why was the dancing at the wedding so drunk and disorderly? People in those days knew the steps. At least the traditional costumes from Opera Memphis, where Canty is general director, kept the story grounded in its time and place. Updating does not often work on the big stage.

It needs to be said that this production represented a lesser level of technical ambition than the son et lumière version of Verdi’s Macbeth given in the pre-renovation Amp in 2015. I suspect I was not the only one who felt that full advantage had not been taken of the new accoutrements.

Music, of course, is the main thing. The Chautauqua Opera orchestra strings in the spacious pit were lush. Steven Osgood is a big-statement conductor. If a few tempos were slow, it was good to hear legato used to underline the manipulative nature of the villain at the center of the story. Woodwinds spoke sweetly in “Mi tradi.” The brief choral interludes were effective.

Don Giovanni was given in Italian rather than English, the latter for many years being the operatic vernacular of Chautauqua. Few companies now trouble themselves with translation. Experience in the original language is infinitely more useful to young singers. This to say nothing of the greater availability of guest artists who know part in the original language only.

It is common to end the opera with the moral-of-the-story epilogue of the Prague version, which Mozart cut before the Vienna premiere. Who would wish to do without this ebullient music, especially as delivered by a good cast? Still, the best postscript to the Don’s refusal to repent and the horrifying consequences is the spectacle of the multitudes taking communion in the same setting the following morning. Opera at Chautauqua is inevitably a special thing.

Arthur Kaptainis is the classical music critic for the Montreal Gazette and formerly for the National Post. He also writes for Musical Toronto and Classical Voice North America. Kaptainis is a member of the board of the Music Critics Association of North America.