It was once known as “Holy Russia,” a land filled with spiritual heritage that was strongly in touch with the oldest traditions of Orthodox Christianity. But around the turn of the 20th century, this picture-perfect Russia came crashing down thanks to tsarist rule, revolution and the “mad monk” who wouldn’t die.

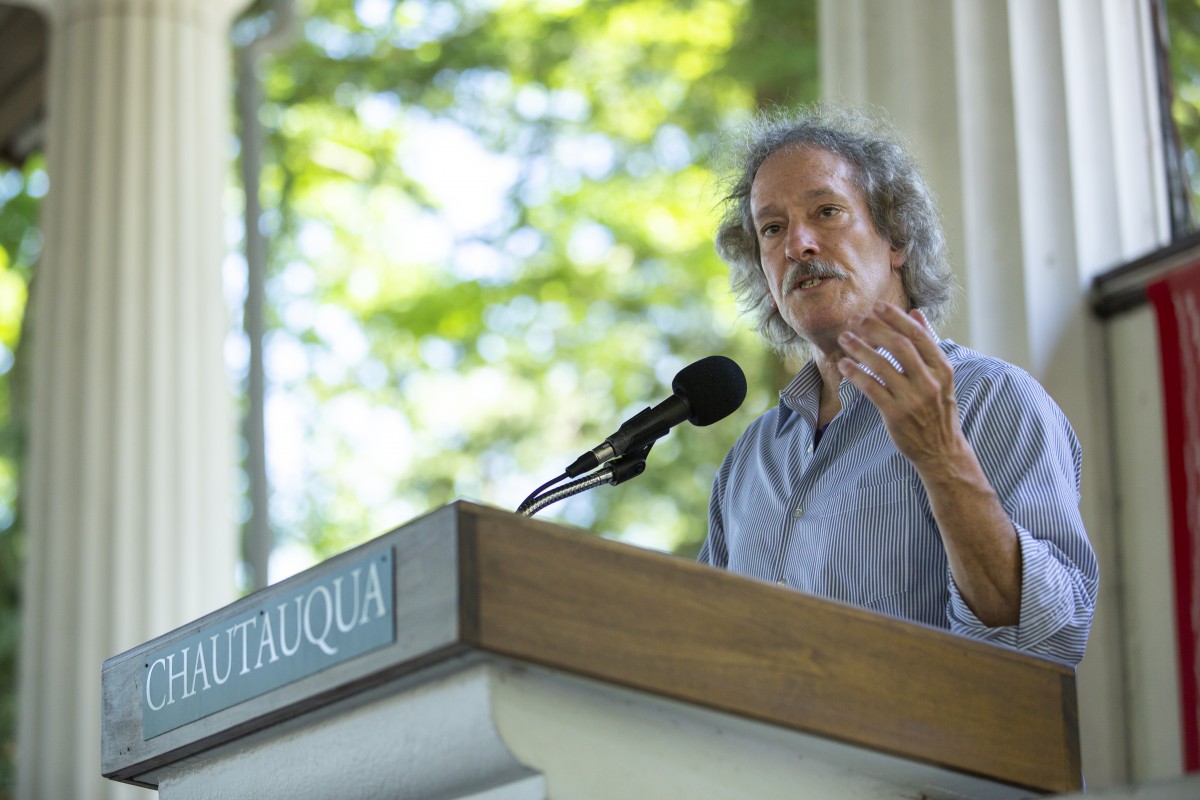

At 2 p.m. Tuesday, July 17, in the Hall of Philosophy, Ori Z. Soltes, a professor at Georgetown University, former director and curator of the B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum and lifelong scholar, discussed how this deadly concoction led to Russians losing their religion in his lecture, “The Drama of Revolutions: Spirituality and Rebirth in the Ashes,” as part of Week Four’s interfaith theme, “Russia and Its Soul.”

Soltes took two steps back in time before talking about the revolution.

The first was to discuss Peter the Great, who Soltes called “both a symbol and a symptom” of the struggle to identify what it means to be Russian.

Peter the Great was crowned the emperor of Russia in 1721. In that same year, he also organized a Holy Synod, led by a secular leader instead of a priest, to take control of the Russian Orthodox Church. However, Soltes said this had no effect on religious practices.

“The Church, in terms of its political power, has obviously been castrated,” Soltes said. “I would argue it did not do much for changing the position of religion among Russian people. The Patriarch is still going to be looked at with the same sort of awe.”

The second step involved Catherine the Great. Catherine was married to Peter III, Peter the Great’s grandson. Peter III was emperor of Russia for six months until Catherine orchestrated a coup and became empress.

She began her reign by absolving churches of their finances, giving church assets to the state. As a result, several hundred churches closed down across the country because they no longer had sufficient funds to function. Soltes believes this still had no effect on people’s spirituality.

“I would still argue that the religion that is within the people is not necessarily going to be undercut, even with the removal of all of those houses of worship,” he said. “They will find other ways, they did find other ways, because it is so (important) to them.”

After Catherine’s death, Alexander II claimed the throne. Alexander was emperor from 1855 until he was assassinated in 1881 by anarchists who called themselves “the people’s will.”

“It is an odd, but not untypical, example of what we are as a species — which is to say we can be so easily confused.”

-Ori Z. Soltes, Professor, Georgetown University

According to Soltes, the decision to kill Alexander II backfired when Alexander III took the throne. Alexander III wanted to avoid ending up like his father, so he reigned in an oppressive and conservative manner. For example, he passed a series of laws called the “May Laws,” which further restricted what opportunities were available to Jews throughout Russian territory.

Alexander III died in 1894 and was succeeded by Nicholas II. Under his rule, the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party split into two groups in 1903: the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks.

“Socialism (was) on a gradual rise across the Russian landscape as there are more and more people, particularly working class people, who are interested in having more rights and feeling less oppressed,” Soltes said. “The rise of the working class was the beginning of the country’s shift in a secular direction.”

Another event that affected religion in 1903 was the Kishinev pogrom, an anti-Jewish riot that took place in what was then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate. Scores of Jews were killed, large numbers of Jewish women were raped and over 2,000 homes were damaged. Kishinev then experienced a second pogrom in 1905.

The first pogrom was clearly motivated by religion because it was led by priests, whereas the second started as a protest against the government and was redirected toward the Jewish community, Soltes said.

“Part of the reason there were pogroms that the government had been somewhat sponsoring was in its efforts, in its interests (and) in its desperation to redirect the antipathy which was growing on the part of the people toward the tsarist regime,” he said.

Both the pogroms and the division of the Workers’ Party led to the beginning stages of the first Russian Revolution, a wave of mass political and social unrest, Soltes said.

The revolution began in 1905 with “Bloody Sunday” in St. Petersburg, where unarmed demonstrators led by the priest Georgy Gapon were fired upon by soldiers of the Imperial Guard as they attempted to present a petition to Tsar Nicholas II.

In the midst of the revolution’s chaos, Nicholas and his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna, were seeking help for their son, Alexei, who had hemophilia. The couple was approached by Grigori Yemovich Rasputin, a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man, who claimed he could help.

In 1907, Alexei was suffering an internal hemorrhage from a bike-riding accident, and Rasputin used the situation to prove his abilities.

“The story is that Rasputin came and saw him, stroked him and prayed for him and the bleeding stopped,” Soltes said.

Five years later, Rasputin was in Siberia when Alexei suffered a second hemorrhage. When the doctors couldn’t stop the bleeding, Alexandra sent a telegram to ask Rasputin for help.

“He writes back very quickly saying, ‘God has seen your tears and heard your prayers, do not let the doctors touch him,’” Soltes said. “Within a day and a half, the bleeding has stopped, and (Alexei) is healed.”

With the second miraculous healing, Alexandra became infatuated with Rasputin. In 1914, the start of World War I, Nicholas II left to cheer on the troops, leaving Alexandra and by default, Rasputin, in charge. According to Soltes, this showed that Rasputin had an “influence over the political present and possible future of Russia.”

In July of that same year, an assassination attempt was made on Rasputin. A peasant woman in his village stabbed him in the stomach.

“As it turns out, this woman was a follower of Iliodor, a former priest who had also initially been a follower of Rasputin, but decided that he was dangerous and denounced him,” Soltes said.

After his brush with death, the way Rasputin conducted his life changed dramatically, Soltes said.

“He began to talk about being ‘being cleansed through sin,’” Soltes said. “So in order to be cleansed of my sins, I have to sin seriously enough to justify the cleansing process.”

Rasputin developed a reputation of being an alcoholic with fondness for orgies and started accepting bribes from people who wanted to gain access to the tsar and his family. Rasputin was seen as “the dark force ruining Mother Russia,” according to Soltes, so in an attempt to save the monarchy, several members of the aristocracy attempted to murder him.

The aristocrats started by giving Rasputin cake laced with cyanide. The cyanide was supposed to have an immediate effect, but nothing happened. After that, they shot him three times at close range, yet he still survived. In a final attempt, the aristocrats threw Rasputin into the river through a hole in the ice, where he died from lack of oxygen.

“It is not clear whether he intended to have political power and influence or if whether he was really interested in gaining some funds to help build a monastery near the place he grew up,” Soltes said. “It all sounds a little bit too constantly connected to have that as the limits of his ambition.”

The death of Rasputin was the last event leading up to the second revolution in 1917, in which Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin led his leftist revolutionaries in a revolt against the ineffective Russian Provisional Government.

Lenin died in 1924, and Joseph Stalin assumed power. By 1934, Stalin began to dictate what kind of art could be produced the Soviet Union. Although tens of millions of Russians were perishing due to famine, Stalin only allowed art that painted a positive picture.

“Religion, even where it can’t prevail, prevails,” Soltes said. “Only, the trinity is Marx, Lenin and Stalin and not the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.”