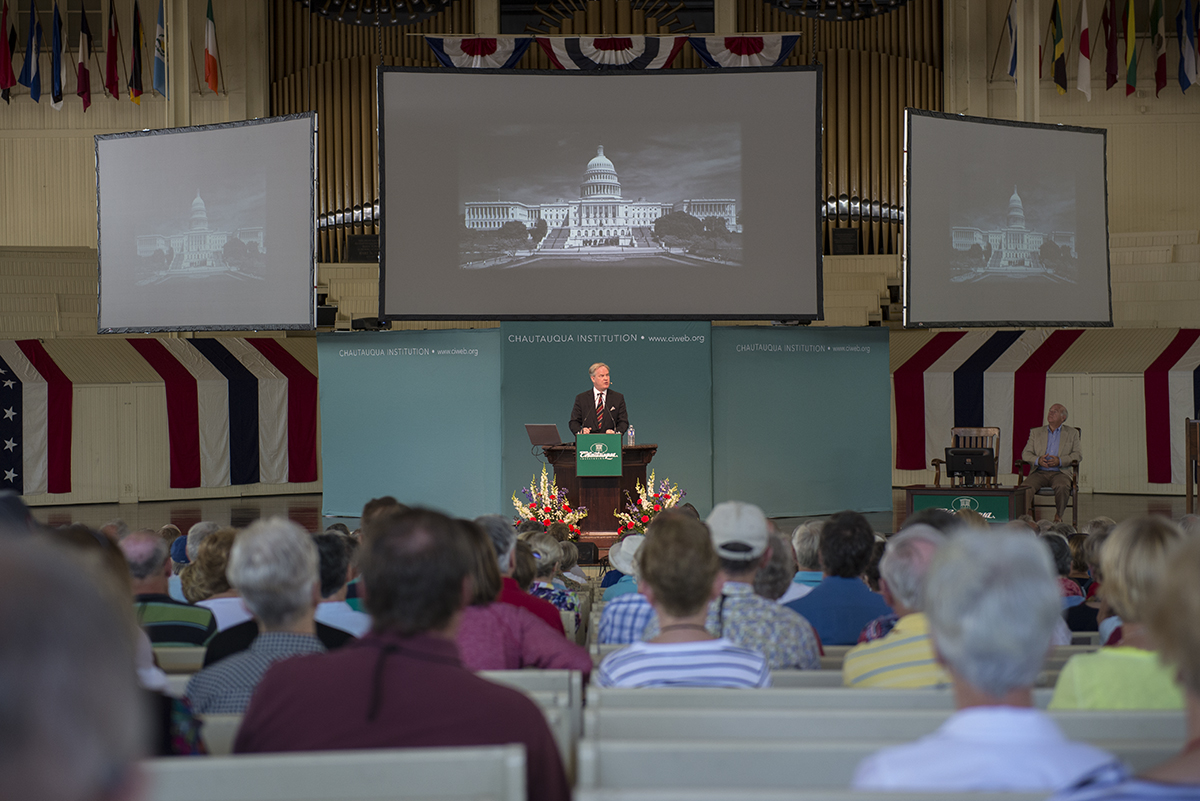

President and Founder of the Campaign Legal Center Trevor Potter kicked off Week Two’s theme “Money and Power” at 10:45 a.m. on the Fourth of July in the Amphitheater by discussing his views on campaign finance reform and how America can reduce the influence money has on politics in the government today.

Potter’s lecture was based on Benjamin Franklin’s response to what form of government the founders were creating during 1787’s Constitutional Convention. Potter said a woman asked Franklin what type of government the nation would have, and he responded, “A republic — if you can keep it.”

“We Americans have been trying to keep our republic ever since,” Potter said. “Through two centuries of domestic and international turmoil, our country has not only seen wars, political upheavals and economic disasters at home and abroad, but also along with these crises, a continuous renewal and expansion of democracy.”

Potter began his lecture by reading the first few lines of the Declaration of Independence, which was crafted to represent America’s freedom from a political system based on wealth and privilege. Instead, the founders of this country wished to build a government where representatives would be responsible for the people.

“The declaration was not merely a statement of philosophy,” Potter said. “Those Americans had real grievances against a government they found distant, unresponsive and run in the interest of others.”

Today, many Americans believe the government is unresponsive and favors those who support campaigns with large-sum donations.

Potter shared a few statistics with the audience, illustrating how Americans perceive the government in today’s society.

In 1964, only 29 percent of Americans believed the government is “run by a few big interests looking out for themselves.” Today, 79 percent of Americans believe that statement, and 75 percent also believe the corruption is spreading.

“This is not the norm for a functioning democracy,” Potter said, citing that only 19 percent of people from Denmark believe that government corruption exists and only 14 percent of Swedes.

Potter said that is due, in part, to the focus on fundraising in politics. This past legislative period, Congress has only been in Washington 54 full days out of 250 possible work days. The other days, he said, were spent fundraising either in home districts or the capital.

Potter quoted retiring Congressman Steve Israel, a Democrat from New York, who said he spent 70 percent of his time as a congressman fundraising.

Politics have become reliant on those who fund its process, Potter said. As a result, Congress focuses on the needs of those who fund them, rather than focusing on the needs of their constituents.

Potter used a recent Supreme Court ruling as an example. In a 5-4 majority, the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to limit the amount of money an individual can donate to all federal candidates and party committees during an election cycle.

The majority’s opinion said Congress is supposed to be responsive to its constituents, which is why the Supreme Court ruled the law unconstitutional.

Potter was appalled by that decision, stating it provides a clear example of Congress focusing on those who donate significant amounts of money rather than the voters who elected them.

“The founders expected the federal government to respond to the voices of the people they represent, not primarily to campaign donors or to lobbyists who fundraise and to the narrow interests those lobbyists represent in Washington,” Potter said.

Currently, presidential candidate Donald Trump spoke on that idea from the perspective of a businessman who has donated to political campaigns in the past. In an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Trump said, “When you give, they do whatever the hell you want them to do.”

An overwhelming majority — 87 percent of Americans — believe “campaign finance should be reformed so that a rich person does not have more influence than a person without money,” Potter said.

That belief fuels the idea that the vote of the average American does not count, according to Potter. More than 50 percent of Americans believe their votes don’t matter because of the influence wealthy individuals have on the electoral process.

“Citizens do not think the government is listening to them or making decisions in the public interest,” Potter said. “They believe the government is now responsive, instead, to special interests and campaign donors.”

Potter argued many of today’s politicians have lost sight of the original vision of the Founding Fathers, including the virtue of compromise. He said some candidates even campaign on the idea of refusing compromise.

For example, a newly elected representative from Colorado was asked during a debate how he would work across party lines. His response was that such compromise “exemplified what’s wrong with America.”

Potter said that further illustrated his point that America’s political system has become polarized with two separate parties fighting to stop the progress of the other.

“The framers intended to promote compromise, not to discourage it,” Potter said. “They expected our representatives in Congress and the president to work together for the national good — not to form two inwardly focused political parties that talk only with the base than with each other.”

Despite the bleak outlook of politics in America, Potter said there is good news. It can be fixed, and there are campaign finance reform bills on local, state and national levels aimed to help eliminate this issue.

He cited a few ideas that would help combat the national issue including: making it mandatory that Congress does no fundraising during the workday; limiting lobbyist fundraising; redistricting to prevent gerrymandering; and refocusing the Supreme Court on the ideas and principles behind the First Amendment.

Potter said there have been previous bills passed that worked toward campaign finance reform and were beneficial, including during the Progressive Era in the early 1900s, after the Watergate Scandal in 1974 and the McCain-Feingold Act in 2002.

“I suppose the cynics in the room could say the fact that these previous reform efforts did not stick means that it is not worth trying again now — that special interest will always find a way,” Potter said. “However, I believe that the correct conclusion to draw from the last century of battles over money in politics is a different one: there is no silver bullet good for all times. We have to keep at it.”