“There is a method in my madness,” said the Rev. Barbara Brown Taylor. “I took our favorite stewardship passages and let them loose and so far they are refusing to serve the purpose for which they are usually used.”

The rich young man could not follow Jesus but Jesus’ love for him was unconditional, and when the widow who gave her last coins turned her face, Jesus saw pain and despair, not contentment.

Taylor was preaching at the 9:15 a.m. Wednesday morning worship service. Her title was “The Parable of the Fearful Investor” and the Scripture reading was Matthew 25:14-30. Often called the parable of the talents, she noted that a talent weighed about 20 pounds and would take an average person about 20 years to earn.

That is not only a disturbing parable, it is near the top of the list.

“The master is so repellant and the servant is blamed for telling the truth and is thrown into economic hell for lack of talent — get it? — at banking,” she said. “But when did we get attached to the idea that we have to agree with everything Jesus said?”

For 100 years, Biblical commentaries have said the servant was wrong, he was risk-averse. But sometimes how you hear a parable depends on where you stand, Taylor said. A homeless man was helped with his addiction, got advice on how to find a job and how to qualify for housing. “Why do you want to fix me up and feed me back to the same machine that ground me up?” he asked the social worker.

The Gospel in Solentiname was published in the 1970s by Ernesto Cardenal. For many years, the peasants in Solentiname, a remote archipelago in Lake Nicaragua, gathered each Sunday to reflect on the Gospel reading. What they had in common was living below the poverty line and fighting against Anastasio Somoza’s regime in Nicaragua. Taylor described the campesinos’ response to the parable which was not positive.

In Jesus’ time, the wealthy made money in trade, and lending money, especially to the land-poor during a drought or a time of illness.

“People got the best interest rate they could, but by the time they realized what 60 percent meant, it was too late. After they were foreclosed on by the lender, they could stay on the land, which they had picked every stone out by hand, and watch it repurposed as a vineyard or olive grove,” Taylor said.

Because most financiers went abroad, their well-placed slaves became domestic bureaucrats.

“They shared in the honest graft that reflected the standard of their household. Whatever their standing, they lived on the master’s excess; their wealth came from his, “ she said. “If he wore nice suits and had a big house, that was good advertising. He was inviting them into his wealth; if they were trustworthy in a little, he would trust them with more.”

“When did we decide the man on the journey was God? How did we turn a master into the Master?” Taylor said. “There have always been masters of this kind and it is hard to see anything but a tycoon.”

The servants are encouraged to double the money any way they like and deduct their expenses to the fullest extent of the law.

“Do we seriously believe these servants are praiseworthy for making the wealthy, wealthier, for giving him a 100 percent return on his investment?” she said.

The third guy buried the money where it could not do any harm and he is the one who is called overcautious. He is thrown into the outer darkness, but what if this is where all whistleblowers live?

Dignity Village is in Portland, Oregon. Fourteen years ago, the city made a contract with homeless people who were living there in tents to move into tiny, handmade houses. Lisa Larson, one of the inhabitants, said it is a big, dysfunctional family, but if you are lonely, someone will be there. The residents pay $35 a month and work 10 hours a week for the community, but there are still no flush toilets in the area after 14 years, she said.

“What if Jesus said to Lisa, ‘I’m back and where is my profit? I am going to take all your stuff and get back into business.’ I can’t imagine that,” Taylor said. “It is entirely possible that Jesus was disappointed that we were willing to swallow the story whole. God is not that kind of master and he exposes that in the Torah, parables and life of his son.”

“Maybe this is a parable about how to read Scripture, that we should not be afraid to reconceive the meaning when we gather together around a book,” she said. “We should let what is on the page rub against our lives and let the friction yield a new truth. Maybe that will help some harsh masters, and wouldn’t that be something?”

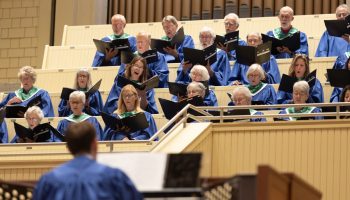

The Rev. Luke Fodor presided. Madison Williams, an intern with the International Order of the King’s Daughters and Sons, read the Scripture. Williams is a senior at Southeastern Oklahoma State University majoring in sociology and political science. Jared Jacobsen, organist and coordinator of worship and sacred music, directed the Motet Choir. The choir sang “Cantate Sing to the Lord,” by Jim Leininger.