If one traveled back to the Selma marches of 1965, one would not hear silence, or even the continuous thud of marching feet. Instead the dominant sound would have been the hum of African-American spirituals such as “We Shall Overcome” and “Woke Up This Morning (With My Mind Stayed On Freedom).”

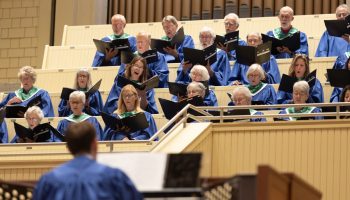

At 3:30 p.m. August 24 in the Hall of Christ, the African-American Denominational House will host a session called “Music and Social Movements.” Half lecture, half experiential concert, the session will explore how music has promoted social change during the civil rights movement and throughout American history and then invite attendees to join in singing some of those key melodies. Louise Toppin, chair of the music department at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, will lead the session.

“Some of things Dr. Toppin will perform will hint at [the civil rights movement],” said Sterling Freeman, AADH project manager. “For the African-American experience in general — sort of the macro experience — and certainly for the African-American faith experience in particular, music is like breath.”

Freeman quoted Wyatt T. Walker, chief of staff for Martin Luther King Jr., who said that during the civil rights movement, African-American spirituals provided courage and affirmation that activists were in the right.

Toppin will start before the civil rights movements, Freeman said, with spirituals that slaves sang in the Antebellum South. Freeman said she will likely go all the way through the recent rise of racial justice activism today.

Although spirituals are less prominent in modern racial justice activism as they were during the 1960s, Freeman said they are still alive in protests like the Moral Monday movement in North Carolina, which has fought for greater voting rights, funding for public education and against discrimination. When the Rev. William J. Barber II, founder of Moral Mondays, spoke at Chautauqua during Week Six, Southern gospel musician Yara Allen led Chautauquans in the same hymns they sing at the North Carolina protests.

More commonly, Freeman said, popular music such as hip-hop and rap have become part of social change. He cited Kendrick Lamar, whose lyrics touch on themes of black pride, discrimination and police violence against black people.

The session is part of a broader attempt to establish the African-American Denominational House’s presence on the grounds and add to the Chautauqua experience, Freeman said. The Chautauqua Institution Board of Trustees officially approved the house in May. The AADH board is still raising funds to give the denomination a building. The organization led a session on structural power and race and one on community last year, and a session on moral leadership in Week Three this summer. Freeman said he hopes to reach across interfaith, interracial, intergenerational and ecumenical lines to bring messages from the black church to Chautauqua.

“[We bring that] black prophetic theological tradition that brings both a critique of our current tradition, but also this note of hope of helping us lean into who we can be in our country and even our world,” Freeman said.

Freeman said he wants this to be an additive experience that draws on the diverse community already at Chautauqua.

“What they can expect: Diversity and inclusiveness, not only in the people that we draw to our programming, but also in the ways that we do things,” Freeman said. “We want to be able create a space where we’re able to get the community involved and draw from the wisdom of the people here.”