Note: This is the third in a series of occasional columns that examines some of this year’s CLSC selections and how they fit into the broader conversation about contemporary literature.

Of all the things in the world, Paul Beatty’s The Sellout made me think about a particular scene from “Game of Thrones.”

Daenerys Targaryen — a fair-skinned, white-haired queen with a brood of dragons — has finished her grand liberation tour of three slave cities, breaking chains and freeing people along the way. Ensconced in the city of Meereen as its ruler, she holds court with a former slave named Fennesz. He makes a request: He wants to sell himself back into slavery.

He has lost his home and his purpose, he says, but Daenerys balks at his wanting to return to a master who owned him “like a goat or a chair.” Fennesz insists.

The queen relents.

“I did not take this city to preside over the injustice I sought to destroy — I took it to bring people freedom,” she says. “But freedom means making your own choices.”

It is a quiet moment, a wrinkle of reality in the show’s sweeping fantasy tapestry. Daenerys wants to learn how to rule, and Fennesz forces her to reckon with an important distinction: freeing people is one thing; freedom itself is something else entirely.

It’s an old idea. Toni Morrison describes it better than I ever could in Beloved: “Freeing yourself was one thing; claiming ownership of that freed self was another.”

And it’s an idea that Beatty pokes and prods and plays with in The Sellout. And I truly mean “plays.” This is a funny, funny book.

The wicked humor of The Sellout comes from Beatty’s fearlessness in presenting the reader with subversion after subversion. Often, over the space of a paragraph, he would take me from laughter to acute terror.

This starts before the book even properly begins. The cover of the novel reappropriates what’s become the racist imagery of the lawn jockey, presenting a pretty pattern of pink-clad men. The book is literally bound in subversion, a thrilling glimpse of its true nature.

There’s an early scene in which Hominy Jenkins — a family friend of the book’s narrator, Me, and one of Beatty’s key agents of provocation — attempts to hang himself with a bungee cord. When Me stumbles across the old man naked and suspended from a tree, he refers to Hominy as a “self-lynching drama queen.”

By hanging himself, Hominy saps the power from the act of lynching. He turns it into something he is doing to himself, not something that is being done to him. It becomes his choice. Me sees him as a diva, not a victim.

Hominy’s act of desperation leads the two to conspire to put their hometown, Dickens, back on the map. The state of California has removed it to save itself from further embarrassment. It is a literal erasure, and Me and Hominy decide to draw a line in the sand.

They do so by reinstituting slavery and segregation. Hominy makes himself Me’s slave, and when Me tries to set him free, Hominy says that “true freedom is having the right to be a slave. … Freedom can kiss my postbellum black ass.”

It’s radical. Beatty takes these deadly acts of discrimination and puts them into the hands of the disenfranchised, giving them the freedom to do with them what they will. His reappropriation of these reviled institutions into a means for change is the source from which the book draws its humor — and its power.

And no institution is safe from Beatty’s delightful, relentless interrogation, including the highest court in the land. The novel begins and ends in the Supreme Court, where Me is put on trial for his actions, much to his annoyance.

In one of the trials leading up to Me’s Supreme Court case, a judge summarizes the issue that’s been brought before him.

“ ‘I don’t care if you’re black, white, brown, yellow, red, green, or purple,’ ’’ Judge Nguyen says. “We’ve all said it. Posited as proof of our nonprejudicial ways, but if you painted any one of us purple or green, we’d be mad as hell. And that’s what he’s doing. He’s painting everybody over, painting this community purple and green, and seeing who still believes in equality.”

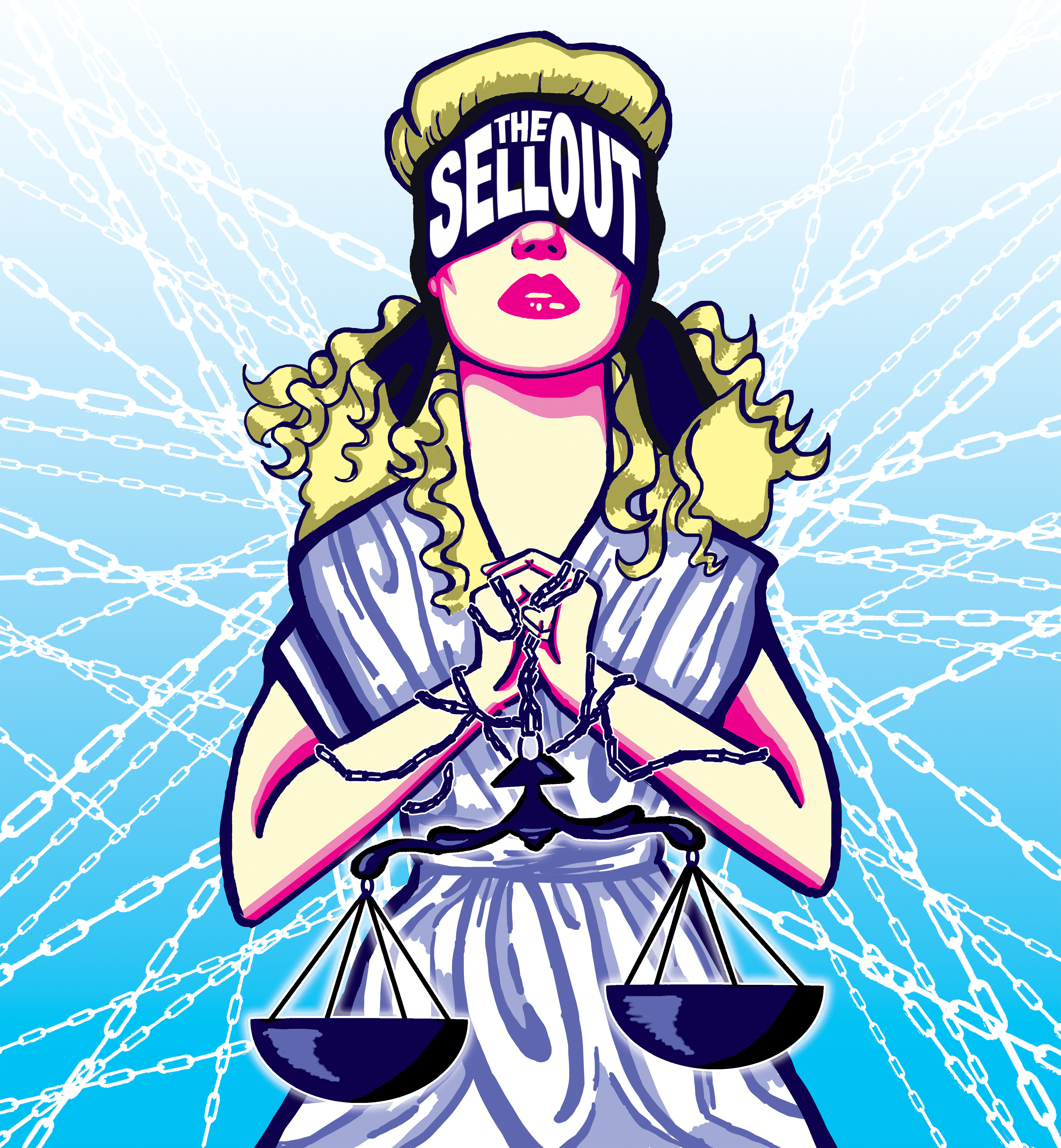

We are taught that justice is blind — that in the eyes of the law, people are equal.

But Beatty yanks the blindfold off and reveals a deeper, uglier truth. The book is funny, yes. It is also terrifying.

Beatty himself has rejected labeling the book as a satire. He says in his interview with The Paris Review that calling The Sellout a comic novel or satire is a way “just to hide behind the humor, and then you don’t have to talk about anything else.” Beatty elaborates, saying he sees it more as a tragicomic novel. I think he’s right. To see it just as a satire is to do it a grave injustice and disservice.

As I reviewed my notes on the book, I came across a scene at a cinema festival, where Hominy questions what blackface is — he just calls it acting. The audience eats it up.

“They thought he was being funny, but he was dead serious,” Me explains.

Couldn’t the same be said for The Sellout? Can’t it be both?

Ryan Pait is in his fourth summer as the literary arts reporter at The Chautauquan Daily. He holds a bachelor’s in popular culture studies and a master’s in literature from Western Kentucky University.