Long before the internet, blogging and social media, journalists were unmasking and explaining the wrongdoings of corrupt institutions for the public. One such reporter was Nellie Bly.

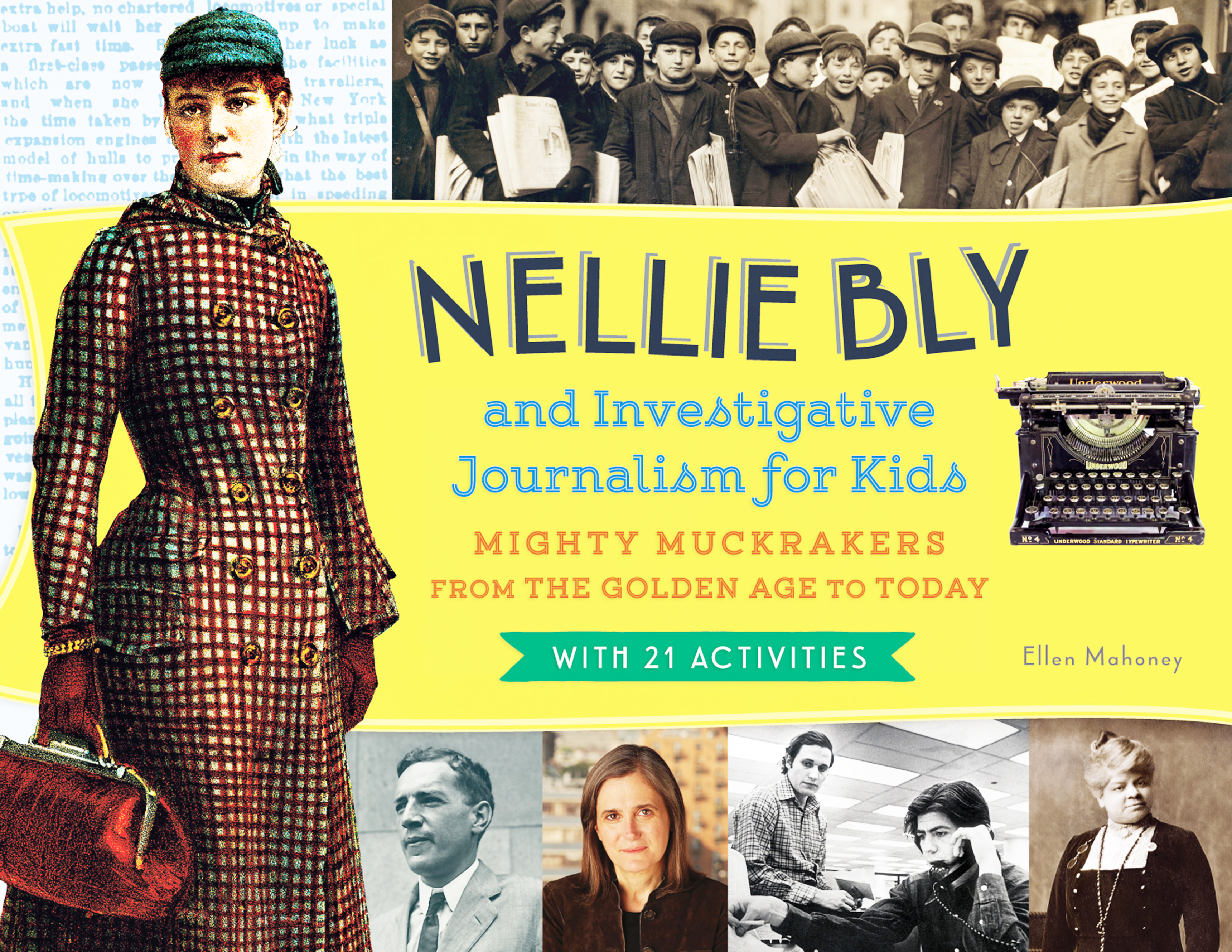

In Nellie Bly and Investigative Journalism for Kids: Mighty Muckrakers From the Golden Age to Today, Ellen Mahoney introduces children to journalism through an engaging and interactive story about Bly and other famous journalists throughout history, like Ida Tarbell, Jacob Riis and Upton Sinclair. Mahoney’s book is this week’s CLSC Young Readers selection and will be discussed at 4:15 p.m. Wednesday in Smith Memorial Library. Members of The Chautauquan Daily staff will be on hand to discuss what journalists do and explain how to write letters to the editor.

“Nellie Bly started her career quite young, so she’s relatable for young readers,” said Mahoney, author and affiliate faculty professor in the department of journalism and technical communication at Metropolitan State University of Denver, and adjunct professor in the College of Media, Communication and Information at the University of Colorado Boulder. “She’s a natural draw, she lived her life fully without too much fear and did many amazing things that I think young people today would admire.”

Mahoney takes readers on a journey through Bly’s professional life. From Bly’s early letter to the editor that got her her first job at the Pittsburgh Dispatch to her trip around the world in 72 days, readers learn about Bly’s career breaking norms as a female journalist in the late 1800s.

In Bly’s time the field of journalism was dominated by men, who, Mahoney writes, were considered “tougher and better skilled to go into the field and report.” But that didn’t stop Bly from pursuing her goals. As opposed to writing about fashion, food, art and other society topics female writers of her time focused on, Bly wrote about hard-hitting issues and often went undercover to do so.

One of Bly’s most notable projects was her articles and book, Ten Days in a Mad-House, about her time spent undercover at Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum.

In her book, Mahoney goes beyond explaining what Bly reported on and shows how Bly’s work helped bring about change for the better. Mahoney writes that after Bly’s articles about Blackwell’s Island were published, an investigation was conducted resulting in more funding, improved living conditions, the release of some patients and the firing of a number of nurses at the asylum.

Although modern-day journalists aren’t able to go undercover in the same way as Bly and her fellow muckrakers, as it’s seen as untrustworthy, Mahoney said, the muckrakers “modeled writing that will always be important for our world.”

Matt Ewalt, associate director of education and youth services, said that while the tools available to journalists have changed, the fundamentals haven’t.

“The overabundance of information so easily accessible at our fingertips makes us often overlook, or at least underappreciate, the great investigative journalism being done today,” said Ewalt, a former journalist and editor of The Chautauquan Daily, where Tarbell herself worked during the paper’s days as the Assembly Herald. “The skill and determination required in gathering and analyzing data, the putting oneself in harm’s way in pursuit of the truth, and the honed craft necessary to tell complex stories.”

Mahoney has been writing since she was a little girl, creating newspapers for her neighborhood along with her friend, and encourages children to do the same. She said children shouldn’t be afraid to pitch an article to a local paper because editors are interested in having young people write.

Throughout her book, Mahoney includes 21 activities that will help children become comfortable with journalistic skills and ways to tell stories. The “My Town” photo essay activity, inspired by photojournalist Jacob Riis, encourages children to take photographs of their hometowns. Another activity includes instructions on how to “make a writer’s block,” which gives ideas on how to be motivated when experiencing writer’s block.

If children are interested in journalism, Ewalt said they “should do what they’ve always done better than adults: Keep asking questions.”

Mahoney writes that when Bly began working at the Dispatch, she wasn’t a “polished writer or seasoned journalist,” but she was able to write “compelling, provocative, and descriptive pieces that readers found interesting and relevant.” Bly drew her inspiration from her own life and the world around her, writing about issues that affected her directly, like the challenges of being a woman.

“Young people can think about what is important them in the world,” Mahoney said. “Always ask, ‘Is there something in the world that bothers you?’ That’s a great way to find an idea of what to write about.”

Words have power, Mahoney said. It is through words that journalists are able to tell the truth and “make a positive difference in the world.”

Mahoney said it can be intimidating for children, and even her college students, to read about Bly and other famous journalists, but it’s important to remember they’re just like everyone else. She said that Bly was a regular person who wanted to make a career out of writing — and did.

“You have to desire to do something, but you also have to go out and do it and make things happen,” Mahoney said. “You can’t just dream and think about it, you have to put the pen to the paper and write.”