Iraqi soldiers stole incubators from Kuwait hospitals and left the babies to die.

Hillary Clinton ran a child prostitution ring out of a D.C. pizzeria.

Tilapia is worse for you than bacon.

These are all eye-catching, interest-baiting headlines. They are also all lies.

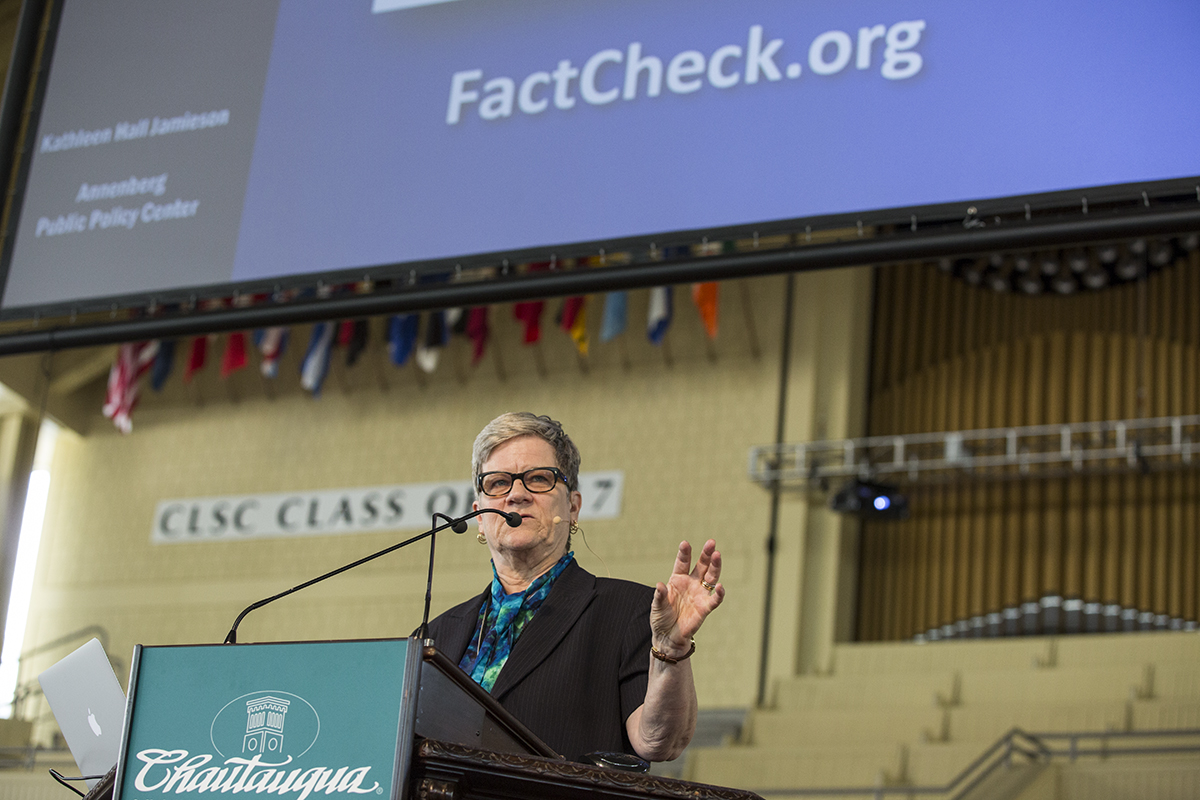

Speaking Tuesday morning in the Amphitheater during Week Eight, “Media and the News: Ethics in the Digital Age,” FactCheck.org co-founder Kathleen Hall Jamieson explored why these lies spread and how they can be stopped.

“I want to set up two premises to start at the top,” said Jamieson, the Elizabeth Ware Packard Professor of Communication at the Annenberg School for Communication and Walter and Leonore Director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. “The first is (that) political deception can matter, and the second is that the advent of what is called fake news — or what I call viral deception — increases the power of deception.”

Passed from person to person, and friend to friend, these misleading or flat-out false narratives rise in credibility as more and more people share them online.

And with each additional click, she said, public discourse is degraded just a little bit more.

The stakes of fake news extend beyond just the ones and zeros of the digital world, though.

“Deception is problematic because it can mobilize national action which you might not take in the absence of deception, it can mislead the electorate, it can invite non-responsive policy, … it can impugn character, and it can even endanger lives,” Jamieson said.

Deception can come from politicians, as with President Barack Obama’s promise that “if you like your health care plan, you can keep it” and President Donald Trump’s claims of “42 percent unemployment.”

But it can also be propagated by political operatives (like Nayirah al-Sabah’s congressional testimony about Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait), media organizations (like the Daily Mail’s allegations that First Lady Melania Trump was once an escort) and fake news websites (like those that pushed the “Pizzagate” conspiracy theory).

It is the veneer of authority, however, that allows all of these — and especially the last two, which went viral — to get away with blatant falsehood.

“The reason that fake news was called fake news was (because) it’s engaging in identity theft,” Jamieson said. “It’s pretending it’s news by looking like news, and as a result, you might be deceived.”

Fake news is not, she clarified, merely information one disagrees with.

Viral deception, meanwhile, need not adopt the guise of legitimate journalism. Instead, it consists of any harmful content spread between people — much like, as Jamieson cheekily noted, another infamous “VD.”

“Deception is problematic because it can mobilize national action which you might not take in the absence of deception, it can mislead the electorate, it can invite non-responsive policy, … it can impugn character, and it can even endanger lives,” Jamieson said.

“Viral deception has deceptive content, it digitally transmits to like-minded individuals, its actual source or its authorship is not disclosed and, importantly, when it is called out as being inaccurate, it is not corrected,” Jamieson said.

Playing a clip from Alex Jones’ “Infowars,” wherein the conspiracy theorist claims that NASA is running a slave colony on Mars, she noted that “most of us don’t believe that, but if people do, we need to be concerned.”

Even something that seems funny, like USA Today’s coverage of nonexistent “selfie shoes,” exemplifies this phenomenon.

Ending either of these twin scourges means understanding how they work, though.

“Human vulnerabilities make us susceptible,” Jamieson said. “We’re prone to uncritically accept and spread content we agree with, and we don’t think before we do that. Once we accept misinformation, it’s remarkably tenacious. We’re prone to accept information consistent with what we already believe, and familiarity equals perceived accuracy.”

“These are tendencies that we all experience,” she added. “Including journalists; including people who run FactCheck.org.”

As evidence, Jamieson referred to a Pew survey showing that a quarter of U.S. adults had shared fake news, as well as a recent meta-analysis of relevant research revealing that “misinformation tends to persist even in the face of debunking.”

In yet another study, “people rated familiar fake news as more accurate than unfamiliar real news,” Jamieson said.

In the face of these “human biases,” how can the effects of fake news and viral deception be mitigated?

Long-form journalism, like that which FactCheck.org produces, provides one answer.

“If we can get you to read the whole correction, it will displace the misinformation,” Jamieson said. “But if we just tell you our conclusion — ‘It’s misleading’ — and even if we just say, ‘It’s misleading because’ and just give you one sentence, we’re far less likely to get rid of the misperception.”

Audio and video journalism also work well, as they can penetrate the deeper levels of belief that short-form writing cannot.

Cutting lies off at the pass also works. When Melania Trump sued the Daily Mail over their escort claims, she stopped the fake news from spreading, got a retraction printed and disincentivized future claims.

Gatekeepers like Facebook and Google can also help, as with the former’s post flagging and verification systems and the latter’s autocorrect and search result algorithms.

“They’re minimizing the likelihood that those who are pushing the viral deceptive content out are being rewarded by getting the clicks, and hence the revenue,” Jamieson said.

Broadcast media also has tools with which to combat inaccuracies, using things like chyrons and video evidence to dispute political claims in real time.

And over time, consistent repudiation can overwhelm even deeply entrenched misbeliefs.

“There are times in which continuing to pursue a correction over time ultimately creates an effective change in the discourse,” Jamieson said.

Presenting articles from conservative press like the The Wall Street Journal and Fox News, she pointed out how long-term debunking of Obama-era birtherism eventually created a bipartisan rejection of the claim, up to and including one of its lead propagators: Trump.

Outside of media, corporate and political entities, though, the average citizen can also work against fake news and viral deception. But they need to be equipped to do so.

“The ultimate protection is arming the public to detect deception,” Jamieson said.

One way to do this is to attack inaccuracies through unconventional mediums; for instance, “The Daily Show” has access to a younger demographic than more traditional news media do.

“The question is, can we find venues like this that reach younger conservative audiences as this reached younger liberal audiences?” Jamieson asked.

In an animated FactCheck.org video titled “How To Spot Fake News,” she revealed other strategies that everyday readers can use when evaluating a given piece of news for accuracy:

- Consider the source

- Read beyond the headline

- Check the author

- Ask what the support is

- Check the date

- Consider if it’s a joke

- Check your biases

- Consult the experts

Jamieson went on to say that misinformation falls into certain prescriptive formats or reuses particular techniques. Awareness of these strategies helps reduce their efficacy.

“We need to learn to detect patterns of deception,” she said.

One way FactCheck.org has tackled this issue is by producing a series of satirical attack ads set during the 1864 presidential election. The campaign reveals popular manipulation tactics without having to take into account modern-day political biases.

Played out in the characters of Abraham Lincoln and George McClellan, three such strategies — “taking things out of context, guilt by association and insinuating deception into a pattern of acceptance” — are brought to light.

Testing has shown this material effective at increasing awareness of manipulative techniques.

But when put back in the modern-day political environment, things get more complicated.

“It’s very difficult to recognize deception when our own ideological side is engaging in it,” Jamieson said. “And so we’ve created an example in which each side is using exactly the same deceptive move, in the hope that people will see that their side did it too.”

The example, a video called “Death By Wheelchair,” depicts a politician pushing an elderly, wheelchair-bound woman off a cliff in the context of a health care-themed attack ad. But the face of the killer is left unseen, and it remains up to the viewer to determine whether it was Obama or Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.

Thus, both sides of the aisle are shown to be guilty of using strategies like “pseudonymous sources” and “a dramatic visual.” Manipulation is bipartisan.

Media consumers need to be wary of these sorts of techniques, Jamieson said. And they need to call them out even if it is members of their own side using them.

And through persistent work against fake news and viral deception on an individual level, they can be ended.

“We can really dampen down the effects of viral deception with the help of these structures if we recognize that the most important protection in this process isn’t (Facebook and Google), although they’re all important,” Jamieson said. “But rather, the ultimate protection is all of us.”