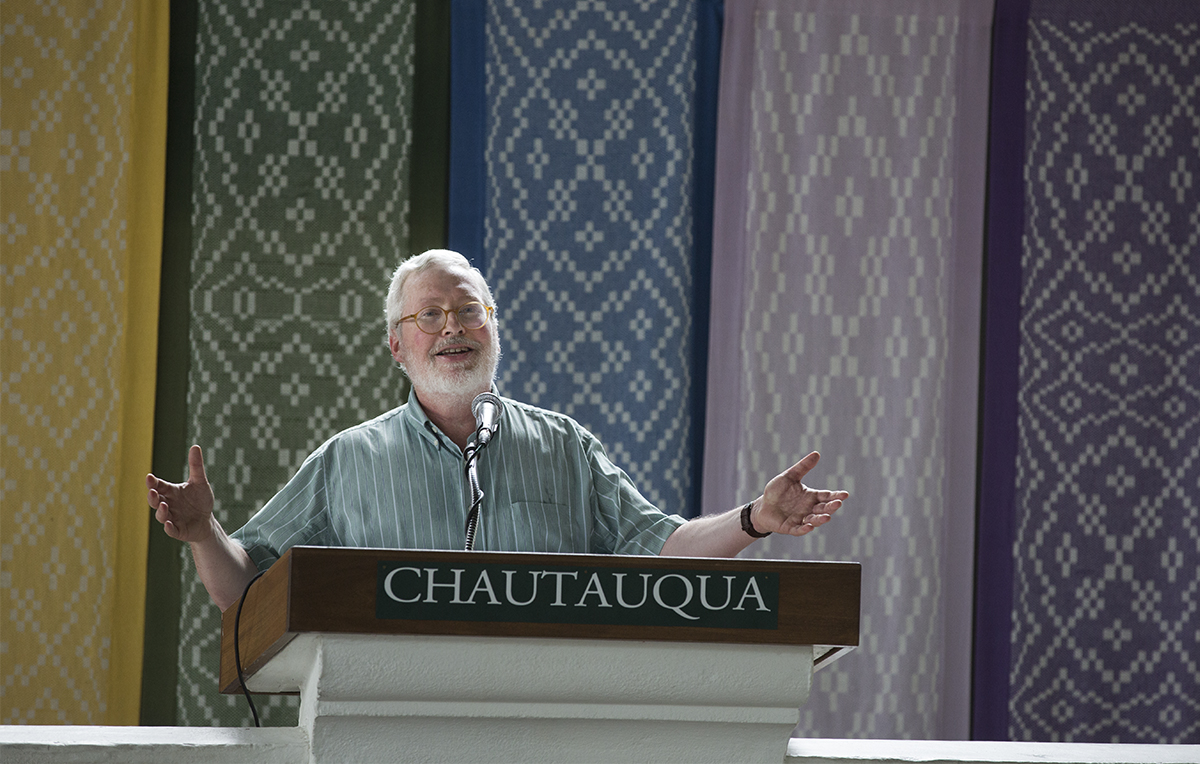

Rabbi Jonathan Brumberg-Kraus probably was not expecting a tornado watch to interfere with his Tuesday talk.

Despite thunderstorms and a delay in the middle of his Hall of Philosophy lecture, “Food, Faith and Fellowship: Connecting to Human and Other than Human Beings through Taste,” Brumberg-Kraus expressed most of the points he was hoping to make as they related to Week Nine’s Interfaith Lecture Series theme, “Food and Faith.”

His hope was to advance three basic themes: first, that religion is “respecting relations between human and other-than-human persons”; second, that food is a “fundamental way of relating to others”; and third, that we connect with others through taste.

At a basic biological level, the act of eating asks us to distinguish what will benefit us versus what will harm us, said Brumberg-Kraus, professor of religion and coordinator of Jewish studies at Wheaton College.

“Our evolutionary, selected, hardwired, human animal instincts equip us to recognize what to eat, with whom to mate and whom to avoid as predators,” he said. “Like all animals, we must determine what is food and what is not.”

Otherwise, it’s like having a stuffy nose and not being able to tell the difference between an apple and an onion. We must combine taste, smell and touch — methods of intimate contact — if we want to experience something to the fullest.

“It’s this intimacy that the first lines of the Song of Songs in the Bible poetically evoke for me,” Brumberg-Kraus said.

“Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth, for your love is better than wine,” he quoted.

This book of the Bible is well known for its food metaphors, often comparing eating to the sensation of physical intimacy. This is not a coincidence, Brumberg-Kraus said. Tasting in and of itself is a relationship between our food and us, expanded to a relationship between us and the earth.

“Our evolutionary survival depends on our instinctive taste and other sensory connections to the world and its inhabitants,” he said. “For it’s our sense experiences that pre-consciously trigger us to fight or flight, to embrace, to inject, to avoid or expel or disgust.”

Why are these responses to food so natural? Brumberg-Kraus suggests it’s because nourishment has roots in Genesis.

“Is it coincidence that the Bible attributes our ability to distinguish between good and evil to an act of eating fruit from the tree of knowledge?” he asked.

Once Adam and Eve eat the apple, though, Brumberg-Kraus said, the holy text gives a mixed message about the fruit’s purpose. On one hand, it acts as a gateway to being elevated above God, and on the other hand, it works as a taboo to be met with a punishment — difficult work for men and the pain of childbirth for women.

“Isn’t this punishment basically a backstory for the earthy, painful, material circumstances of our human condition, living in this real world?” Brumberg-Kraus asked. “Whatever spin we put on it, and even with the technological advances that have eased our conditions, we humans now do have to work to eat.”

He said this act of labor shows that eating is a way of being religious. In Brumberg-Kraus’ definition of religion, he included the “respect of relations” between things that are human and things that are not. And food, as a matter of fact, is “not.”

Brumberg-Kraus knew there could easily be some objection to this idea — for example, if he was classifying food as religious, couldn’t the argument be made that other objects were “religious” as well? And what, then, would stop people from classifying everything as religious?

But many religions, he said, do not have faith at the center of their practice. Instead, in Graham Harvey’s book, Food, Sex and Strangers: Understanding Religion as Everyday Life, faith in religion is seen more as an exception and less as a rule. It wasn’t always like this.

“Because the modern critical study of religion emerged in Protestant-Christian Europe, even those scholars who abandoned their Christian faith or who were themselves not from Christian backgrounds, carried over the bias of stressing belief, or faith, as a central, if not the definitive component of religion,” Brumberg-Kraus said.

Harvey defines religion in four distinct ways: respecting relations, committing acts of violence with impunity, making strangers into guests and practicing etiquette in the real world.

This third point is vividly seen in the practice of communion in the Christian church. By breaking bread together, worshippers are connected to one another and to God by a common belief.

Isn’t this punishment basically a backstory for the earthy, painful, material circumstances of our human condition, living in this real world?” Brumberg-Kraus asked. “Whatever spin we put on it, and even with the technological advances that have eased our conditions, we humans now do have to work to eat.”

As Harvey put it, “Religion is the etiquette of relating within a multi-species world.” But that spirituality, Brumberg-Kraus suggested, can extend beyond familiar rituals.

“To see religion — or to suggest a better alternative as mostly spiritual — wrenches out of material, physical reality that it’s the point of religion to help us live in,” Brumberg-Kraus said. “Eating, and the activities associated with it, keep us grounded in the embodied, material, located reality.”

The biggest obstacle we experience in assigning food spirituality is the terminology itself. It is through our senses, though, that “physical engagement with physical beings … lifts our spirits,” he said. This act turns the tangible into something mystical.

“If alienation, loneliness, dislocation, separation from loved ones (and) hostility directed at ourselves and at others are at the base of the most painful aspects of our human condition, then connection is what relieves it,” Brumberg-Kraus said. “Connecting to the work of our hands, to our missed loved ones, to lost homes, to all kinds of humans and other-than-human persons, uplifts us.”

Scripture, he said, is constant in its mention of food in this way — particularly in Psalm 34:8, in which the author requests readers to “taste and see that the Lord is good; blessed is the one who takes refuge in him.”

Brumberg-Kraus transitioned, presenting this point: Eating encourages us to treat our cuisine as if it were a person. It would be presumptuous to assume that chickens, for example, do not “acknowledge or react to our presence in some way” when we are around. In fact, he said, nature has its own conversational system to discuss human interaction with it.

“Recent studies of trees and mushrooms suggest that collectively, they communicate with one another, albeit in ways quite different than how our physiologies equip us to do it,” he said.

Due to the rain delay, Brumberg-Kraus jumped ahead in his material and listed four places where we engage in negotiation and connection: the kitchen, the market, the garden and the table itself. He wanted to focus on the last.

“At the table, sharing foods, words and indeed, the very air we breathe, creates a different, more intimate relationship between the participants, which tends to curb our potentially more hostile instincts to one another,” Brumberg-Kraus said.

The table presents a friend-making power, the divide between red and blue bleeding into purple when we get together over a meal.

“The family table is where many of us first learn the ideals of civil behavior, even if we don’t always live up to them,” he said. “And as much as I love the idea of culinary diplomacy, I am not so naive to think that meals can smooth over every issue that might divide people.”

But when the focus is on the food, it’s hard to talk about anything else. In his book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Michael Pollan recalled natural conversations unfurling among his friends about the plants on the plate rather than the problems among the people.

“The stories told by this little band of foragers ventured a long way from the table,” Brumberg-Kraus said, “the words, the taste, too, recalling us to an oak forest in Sonoma, to a pine burn in the Sierra Nevada, to the stinky salt flats of the San Francisco Bay, to slippery boulders on the Pacific Coast and to a backyard in Berkeley.”

By telling these stories, we are able to consider the stories of the food in front of us, every item pointing somewhere — toward nature, community or a sacred space.

“Such storied food can feed us, both body and soul, the threads of narrative knitting us together as a group and knitting the group into the larger fabric of the world,” Brumberg-Kraus said, quoting Pollan.

This perspective is indicated in the Jewish blessings for specific gifts — bread, trees, the fruit of the vine and the fruit of the earth, for example. Jews believe that all material things possess a divine energy and that they must distribute that divine energy back to the source. This “cosmic recycling” can be seen in the physical prayer for blessing bread, drawn from Psalm 104:14, translated: “Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the universe, who brings forth bread from the earth.”

“They can taste it and so can we,” Brumberg-Kraus said, “if we have mouths, eyes, noses, ears and fingers to do so.”